American Crucifixion (22 page)

Read American Crucifixion Online

Authors: Alex Beam

In a series of letters sent to his father in Ridgefield, Connecticut, George Rockwell, a dedicated and erudite anti-Mormon, explained how he left his business in the hands of his clerks to campaign full time against the Hancock County Saints. “I can assure that I take much pleasure in lending my humble aid to expel a band of citizens from the state,” Rockwell said, “the leaders of whom are deserving a thousand deaths.” Rockwell lived in Warsaw and wrote stirringly of the old citizens’ travails at the hands of Joe Smith and his followers. “The Mormons were increasing fast in the County,” he explained, “their political influence had been so guided by revelation that it bid fair to sap the very foundations of our government.” Like many self-appointed spokespeople for the old settlers—Sharp and Colonel Levi Williams would be two others—Rockwell had arrived in Illinois only a few years before.

Writing from Alton, about seventy-five miles south of Carthage, Rockwell told his father that he had spent several sleepless nights riding into adjoining counties to recruit anti-Mormon militia brigades. Rockwell was carrying a requisition order signed by Governor Ford, instructing the Alton arsenal to send all of its state-owned muskets and cannon to Warsaw, where several hundred men were intending to march north and invade Nauvoo. With forces assembling in Carthage and Warsaw, Rockwell predicted that “the Mormons will be routed” within the next few weeks.

Unless they should alter their minds and submit to the laws, and lay down their arms, in which event their lives will be spared, (excepting Joe Smith and a few of his advisers) but the City of Nauvoo will be destroyed.

They number 3 or 4000 men well armed and will probably make a desperate resistance. Joe is trying to ape Mahomet, indulges in all kinds of licentiousness and has become a formidable foe to the State.

UPRIVER, JOSEPH WAS PREPARING NAUVOO FOR WAR. THE

LEGION drilled every morning at 8:00 a.m. and remained on alert until the late afternoon. “Every man almost slept on his arms and walked armed by day,” recalled Legionnaire Oliver B. Huntington, “ready at a moment’s warning to lose their lives, or lay them in jeopardy in defense of our rights.” Joseph issued instructions to the city police and to Jonathan Dunham, the major general commanding the Nauvoo Legion: guard the waterfront and station pickets along the roads leading into the city. Nauvoo’s forty-man police force was on high alert, on the lookout for spies, importuning strangers, checking bona fides. The

Expositor

-inspired dissidents numbered just a few hundred at most, in a population of over 10,000 Saints. Nonetheless, Joseph and Nauvoo’s leaders fretted about fifth columnists who might be helping the restive Hancock County militias. “At Nauvoo, a bayonet bristles at every assailable point!” a St. Louis newspaper reported. “Boats are not permitted to tarry, nor strangers permitted to land.”

LEGION drilled every morning at 8:00 a.m. and remained on alert until the late afternoon. “Every man almost slept on his arms and walked armed by day,” recalled Legionnaire Oliver B. Huntington, “ready at a moment’s warning to lose their lives, or lay them in jeopardy in defense of our rights.” Joseph issued instructions to the city police and to Jonathan Dunham, the major general commanding the Nauvoo Legion: guard the waterfront and station pickets along the roads leading into the city. Nauvoo’s forty-man police force was on high alert, on the lookout for spies, importuning strangers, checking bona fides. The

Expositor

-inspired dissidents numbered just a few hundred at most, in a population of over 10,000 Saints. Nonetheless, Joseph and Nauvoo’s leaders fretted about fifth columnists who might be helping the restive Hancock County militias. “At Nauvoo, a bayonet bristles at every assailable point!” a St. Louis newspaper reported. “Boats are not permitted to tarry, nor strangers permitted to land.”

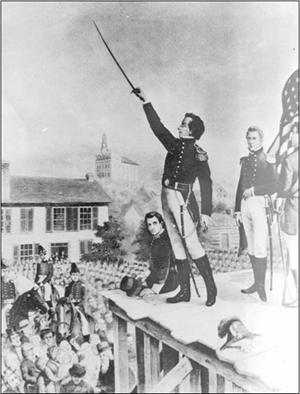

On the following day, June 18, Joseph donned his gold-braided, buff-and-blue brigadier general’s uniform and summoned the Nauvoo Legion to a full-dress review in front of his home. Apostle William Phelps read a brief, inflammatory dispatch from the Warsaw

Signal

, detailing the anti-Mormons’ preparations for war. Standing atop the wooden frame of the unfinished barbershop and inn being built for Porter Rockwell, under a bright sun and a radiant blue sky, Joseph delivered one of his most magnificent orations, a ninety-minute-long self-vindication and stirring call to arms.

Signal

, detailing the anti-Mormons’ preparations for war. Standing atop the wooden frame of the unfinished barbershop and inn being built for Porter Rockwell, under a bright sun and a radiant blue sky, Joseph delivered one of his most magnificent orations, a ninety-minute-long self-vindication and stirring call to arms.

A stylized lithograph of Joseph’s final address to the Nauvoo Legion, with the Nauvoo Mansion in the background; by Mormon artist John Hafen in 1888

Credit: Utah State Historical Society

“We have never violated the laws of our country,” he began.

We are American citizens. We live upon a soil for the liberties of which our fathers periled their lives and spilt their blood upon the battlefield. Those rights so dearly purchased, shall not be disgracefully trodden under foot by lawless marauders without at least a noble effort on our part to sustain our liberties.

“Will you all stand by me to the death,” he shouted, “and sustain at the peril of your lives, the laws of our country, and the liberties and privileges which our fathers have transmitted unto us, sealed with their sacred blood? “AYE!” the serried soldiers, and hundreds of citizens surrounding them, shouted in reply.

“Good!” Smith thundered. “If you had not done it, I would have gone out there”—Smith pointed west, across the Mississippi river—“and would have raised up a mightier people.”

Smith pulled his four-foot-long, tempered-steel cavalry saber from its sheath and brandished the blade above his head.

“Come, all ye lovers of liberty, break the oppressor’s rod, loose the iron grasp of mobocracy, and bring to condign punishment all those who trample under foot the glorious Constitution and the people’s rights!” he shouted. “I call God and angels to witness that I have unsheathed my sword with a firm and unalterable determination that this people shall have their legal rights, and be protected from mob violence, or my blood shall be spilt upon the ground like water, and my body consigned to the silent tomb.”

Joseph again introduced the theme of mortal sacrifice. “I do not regard my own life,” he told the thousands of assembled Saints. “I am ready to be offered a sacrifice for this people; for what can our enemies do? Only kill the body, and their power is then at an end.”

The sword that Joseph unsheathed would never be sullied with a drop of blood. And he would never address the Saints again.

AMID THE RISING TENSIONS, A CARTHAGE “CITIZENS COMMITTEE” traveled to Springfield to ask Governor Ford to call out the state militia to keep the peace in Hancock County. Ford had a different idea. He would journey to Carthage and guarantee the peace himself. He established his headquarters at Artois Hamilton’s hotel, down the street from the county courthouse. The hotel had become the de facto headquarters for the men bent on forcing Joseph to face justice, not only for destroying the

Expositor

but also for evading the Laws’ complaints of adultery and “false swearing” filed in May. Wilson Law, Robert Foster, and the Higbees had taken refuge there, and several of Joseph’s lesser-known enemies hovered nearby. Apostle John Taylor, whom Joseph sent to negotiate with Ford, reported that Carthage “was filled with a perfect set of rabble and rowdies, who, under the influence of Bacchus, seemed to be holding a grand saturnalia, whooping, yelling and vociferation as if Bedlam had broken loose.”

Expositor

but also for evading the Laws’ complaints of adultery and “false swearing” filed in May. Wilson Law, Robert Foster, and the Higbees had taken refuge there, and several of Joseph’s lesser-known enemies hovered nearby. Apostle John Taylor, whom Joseph sent to negotiate with Ford, reported that Carthage “was filled with a perfect set of rabble and rowdies, who, under the influence of Bacchus, seemed to be holding a grand saturnalia, whooping, yelling and vociferation as if Bedlam had broken loose.”

Carthage was a teeming epicenter of anti-Mormon agitation. Attending a mass meeting with several hundred old citizens, Samuel O. Williams, an officer in the Carthage Greys militia, told a friend “that we all felt that the time had come when either the Mormons or the old citizens had to leave.” The wife of Thomas Gregg, an editor and occasional anti-Mormon pamphleteer, wrote to her husband from Carthage: “You have no idea what is passing here now, to see men preparing for battle to fight with blood hounds; but I hope there will be so large an army as to intimidate that ‘bandit horde’ in Nauvoo.” Within just a few days, about 1,300 militiamen and would-be regulators would gather in Carthage. “Strike, then!” Sharp urged his readers. “For the time has fully come.”

The town center had become a vast military bivouac. The three hundred elite Carthage Greys had pitched their tents on the main square and were drilling four hours a day. Militia regiments from neighboring McDonough, Brown, Adams, and Schuyler Counties soon joined them. Journalist B. W. Richmond reported that “about six acres of ground, in the open space in the centre of town, was covered with ordinary camp-meeting tents, and into these the soldiers were crammed pellmell without order or discipline.

Some were playing cards, and others drinking, or boiling potatoes in small iron pots or roasting bits of bacon impaled on sharp sticks, or baking corn-cakes. Many were pretty drunk, and let out without reserve what was going on in the camp. “Death to the prophet!” was the watchword.

In later life, Eudocia Baldwin, who was fifteen in 1844, had rosier memories of the Carthage town square. She remembered that her hometown had become “the scene of great bustle and excitement”:

We children went sometimes to see the drilling and parading—delighted with the tumult and commotion, the music of fife and drum, the waving and fluttering of the stars and stripes in the warm June breezes. The galloping hither and thither of Colonels and Aides de Camp with very rich silk sashes, and very bright swords, shouting

very

peremptory orders—were sights and sounds never to be forgotten by children unaccustomed to any warlike demonstrations. . . .

High above all could be heard the droning and shrieking of the bagpipes, for the ubiquitous Scotchman was there to furnish this to us novel and animating music.

Shortly after arriving, Ford addressed the restive militias, who alternately feared a Mormon attack or wanted to march on Nauvoo posthaste. Ford told the men that he intended to follow the law. The Mormons would answer for the destruction of the

Expositor

, but his audience would have to agree to support the governor’s “strictly legal measures.” In his own account of his speech, Ford reported that “the assembled troops seemed much pleased with the address.” When he finished, “the officers and men unanimously voted with acclamation, to sustain me in a strictly legal course, and that the prisoners should be protected from violence.”

Expositor

, but his audience would have to agree to support the governor’s “strictly legal measures.” In his own account of his speech, Ford reported that “the assembled troops seemed much pleased with the address.” When he finished, “the officers and men unanimously voted with acclamation, to sustain me in a strictly legal course, and that the prisoners should be protected from violence.”

Ford was talking about hypothetical prisoners. Conjuring up the Mormon leadership to stand trial for the destruction of the

Expositor

was easier said than done. Ford picked up on Smith’s earlier letter and initiated a back-and-forth exchange, entreating the Prophet to give his side of the story. Fearing violence, Smith sent two advisers, Taylor and John Bernhisel, to Carthage to meet with Governor Ford. Simultaneously, he fired off a letter to President John Tyler in Washington, asking for “that protection which the Constitution guarantees in case of ‘insurrection and rebellion,’ [to] save the innocent and oppressed from such horrid persecution.” Smith never had much luck with US presidents, and the Mormons’ official history makes no note of a reply.

Expositor

was easier said than done. Ford picked up on Smith’s earlier letter and initiated a back-and-forth exchange, entreating the Prophet to give his side of the story. Fearing violence, Smith sent two advisers, Taylor and John Bernhisel, to Carthage to meet with Governor Ford. Simultaneously, he fired off a letter to President John Tyler in Washington, asking for “that protection which the Constitution guarantees in case of ‘insurrection and rebellion,’ [to] save the innocent and oppressed from such horrid persecution.” Smith never had much luck with US presidents, and the Mormons’ official history makes no note of a reply.

The governor listened to Smith’s emissaries and immediately summoned Joseph and other members of the City Council to Carthage to stand trial. “Your conduct in the destruction of the press was a very gross outrage upon the laws and the liberties of the people,” Ford wrote. “It may have been full of libels, but this did not authorize you to destroy it.” He plaintively added that “there are many newspapers in the state which have been wrongfully abusing me for more than a year,” but Ford insisted he would “shed the last drop of my blood to protect those presses from any illegal violence.”

“The whole country is now up in arms,” Ford wrote, “and a vast number of people are ready to take the matter into their own hands.” If Smith refused to surrender voluntarily, Ford wrote, he would authorize the militias and proto-militias gathered in Carthage to go get him. A war against the Mormons, Ford warned, “may assume a revolutionary character, and the men may disregard the authority of their officers.” In other words, it could turn into a bloodbath.

Other books

Bound By Temptation by Lavinia Kent

Autobiography of a Face by Lucy Grealy

Just a Kiss by Bonnie S. Mata

Entrevista con el vampiro by Anne Rice

Popped by Casey Truman

The Last Town (Book 4): Fighting the Dead by Knight, Stephen

Amulet of Doom by Bruce Coville

Trust Me by Anna Wells

Not Her Type: Erotic Adventures With a Delivery Man by Kay Jaybee