American Crucifixion (33 page)

Read American Crucifixion Online

Authors: Alex Beam

Daniels declined to speculate on the source or the meaning of the light—otherworldly or otherwise. He and Lamborn quietly permitted the messianic implications to leach into the trial record.

Rising to cross examine, occasionally mopping his brow in the stiflingly hot courtroom, Orville Browning knew he had plenty of material to work with. Why, he asked, was Daniels marching out of Warsaw on an anti-Mormon mission in the first place? Daniels said that after he heard the defendants discussing the Smiths’ murder in a tavern the night before, they arrested him. Yet somehow he was included on the foray to Golden’s Point, where his captors disappeared. Well then, said Browning, you were in an ideal situation to ride into Carthage and warn the Mormon prisoners of the plot to kill them. No, said Daniels, that would not have worked, because the fix was in with Worrell and the Greys guarding the jail.

Browning toyed with Daniels for a while, posing a question, waiting for an answer, and then pointing out how the new version of events contradicted the written account in the pamphlet. Were Joseph’s eyes open or shut when Williams’s men executed him? Daniels couldn’t remember. But the pamphlet he authored said Joseph gazed on his killers with “calm and quiet resignation.”

Oh, Littlefield wrote that, Daniels answered.

Inevitably, Browning interrogated the miraculous vision of light:

Q:

At what time did you see this marvelous light?

A:

I saw it at the place after the shooting.

Q:

Well, tell us about that light.

A:

It was like a flash of lightning there at the moment.

Q:

When [Joseph] was shot, did any person go up to him?

A:

Yes, a young man attempted to get him.

Q:

Had he a bowie knife in his hand?

A:

I did not see that.

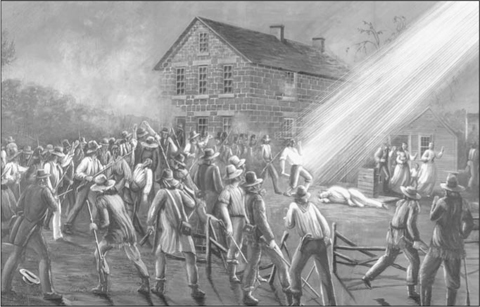

The “flash of lightning” supposed to have illuminated Joseph Smith’s death, reimagined by C. C. Christensen

Credit: Brigham Young University Art Museum

Littlefield had embellished that detail, Daniels testified.

*

*

Now Browning successfully elicited numerous “bad facts” from Daniels, small details of his life sure to imprint themselves on the jurors’ memories. What do you do for a living, Mr. Daniels? Daniels admitted that he had been making a living by exhibiting a painting of Joseph Smith’s death, a painting that incorporated all the baroque details of his published “Correct Account.”

“Do you tell people that the painting is inaccurate?” Browning inquired.

“When asked, I have told that it was not correct but when not asked, I said nothing,” Daniels replied.

Daniels’s greed, or lack thereof, came out under cross-examination. In his published pamphlet, he averred that he had come forward because of a spiritual revelation, but it became clear that he and Littlefield were hoping to turn a quick buck with the “Correct Account.” Furthermore, Daniels had bruited around town that he might be paid to testify—or stay away—from the Joseph Smith murder trial. He said that he had been offered $500 to tell his story at trial, and $2,500 to make himself scarce and

not

talk. Daniels insisted he had accepted neither proposition, but his demeanor left room for doubt.

not

talk. Daniels insisted he had accepted neither proposition, but his demeanor left room for doubt.

It was 6:15 p.m. Judge Young announced that court would reconvene on Monday at 7:00 a.m. The courtroom claques scored Day One a draw. Sharp and Williams were clearly agitating for vigilante action at Golden’s Point. Worrell had muddied the waters, or worse, concerning the Greys’ collusion in the Smiths’ deaths. And Daniels was a crazy fabulist, an obvious millstone around the prosecution’s neck.

THE TRIAL LASTED THREE MORE DAYS, MUCH OF THE TIME devoted to disagreements over who saw what. Several witnesses placed Williams, Aldrich, Grover, and Sharp near the jailhouse carnage, but recollections varied concerning their involvement in the massacre. Sharp was on foot; Sharp was on horseback; Sharp was driving a buggy; Sharp and Williams were in a wagon. Grover and Davis were at the railroad shanties; unless they weren’t. Williams led the attack on Carthage; no, he was already

in

Carthage. Eyewitness accounts wandered all over Hancock County.

in

Carthage. Eyewitness accounts wandered all over Hancock County.

Then Lamborn put a Mormon woman, Eliza Graham, on the stand to recount what she saw and heard on the night of the Smiths’ killings. Graham worked at the Warsaw House, a tavern managed by her aunt, Mrs. Fleming. Around sunset, she said, the editor Thomas Sharp arrived at the tavern in a two-horse carriage and asked for a cup of water. “We have finished the leading men of the Mormon Church,” she heard him say.

As Graham told it, defendants Davis and Grover showed up at the tavern around midnight with about sixty men, including William Voras, who had been wounded in the jailhouse shoot-out. Decompressing at the inn, the men tried to one-up each other with rival claims of having finished off “Old Jo,” according to Graham. Grover claimed to have killed the Prophet, and so did Davis. On cross-examination, Browning made much of Graham’s Mormon church membership and elicited her damaging admission that she had previously pled complete ignorance of the case, to avoid testifying in court.

The final prosecution witness was Benjamin Brackenbury, a young man who drove a baggage wagon with Captain Davis’s militia company. Brackenbury was at Golden’s Point and then followed the irregulars on the road to Carthage. Like Daniels, he said somewhere between seventy and a hundred of them left the road three or four miles outside of Carthage, to approach the jailhouse through the woods. Brackenbury saw all five defendants head into Carthage, and he saw four of them return the way they came. For the record, he also saw three of the absent defendants, William Voras, John Wills, and William Gallagher—all of them wounded—straggling back to Warsaw after the attack. Captain Grover “said he had killed Smith, that Smith was a damned stout man, and that he had went into the room where Smith was, and that Smith had struck him twice in the face.”

Browning laid into Brackenbury, with mixed results. Yes, Brackenbury had partaken of some spirits on June 27, “enough to make me feel nice.” You didn’t actually see Captain Grover go to the jail, did you? Browning asked. No, Brackenbury answered, but when he got into my wagon afterward, “he was talking to Mr. Williams about killing the Smiths.” Grover boasted that he was the first man through the jailhouse doorway and repeated his claim that Smith bashed him in the face. Browning remarked, that was odd, given that he was holding a pistol.

If you can’t attack the testimony, the adage goes, attack the witness. Browning proceeded to do just that.

Q:

What business do you follow?

A:

Loafering.

Q:

And how long have you been doing that?

A:

The most of this winter.

Q:

When did you commence that trade?

A:

A little before last court here [October].

Brackenbury added that he had been living with the Jack-Mormon Minor Deming for several months, and he didn’t know who paid for his room and board.

The prosecution rested its case.

Browning and his colleagues at the defense table spent part of Tuesday and half of Wednesday summoning sixteen witnesses, mainly to impeach Brackenbury, Graham, and Daniels. Some astonishing details emerged. Daniels apparently boasted to two acquaintances that he had personally overwhelmed Franklin Worrell at the jailhouse door, wrestled his sword from him, and threw it over a fence. One of the witnesses said Daniels had no special remorse for the Smiths’ deaths, “as they richly deserved it.” The defense lawyers had rounded up three of Brackenbury’s fellow barrel-makers, or “brother chips,” as they called themselves. They reported that Brackenbury “had quit coopering and never expected to do any more hard work” because he had tripped across a “speculation” that was going to pay him $500, that is, testifying against the men who had murdered the Smiths.

Browning likewise found several witnesses to shoot holes in Eliza Graham’s testimony, including her employer at the Warsaw House, Mrs. Fleming. He rested his case, and court adjourned for lunch, with closing arguments to start at 2:00 p.m.

THAT AFTERNOON, IN HIS FINAL APPEARANCE OF THE TRIAL, THE disheveled Lamborn stood before the jury looking bereft. Walking in apparent pain and leaning on his cane, Lamborn shuffled around the courtroom, hardly the picture of a legal titan marshaling his forces for a stunning peroration.

Lamborn ended his case as he had begun it, on a note of self-pity. The defense had arrayed four talented lawyers against him, the former attorney general noted; he was a stranger from Quincy, unknown in these parts, and so on. Then he loosed a bolt of lightning like the one that Daniels had tried to exploit in his pathetic pamphlet: Lamborn abandoned the substance of his case.

Shocking his onlookers, Lamborn dumped Daniels and his artless confections overboard. Daniels, he said, “has made statements which ought to impeach his evidence before any court.” His pamphlet was obviously “a tissue of falsehoods from beginning to end.” “I intend to be fair and candid,” Lamborn said, “and therefore exclude Daniels’ evidence from the consideration of the jury.” He went further. Brackenbury, who saw all of the defendants march on Carthage, was “drunk, is a loafer and perjured himself before the grand jury. I am satisfied that his evidence can be successfully impeached, and therefore withdraw it from the jury.” He had only one credible witness left—the earnest Eliza Graham. Lamborn disowned her, too: “She is contradicted, and I therefore give her up.”

Lamborn’s awkward self-immolation wasn’t over. “I have no doubt in my mind, not a particle, that [Jacob] Davis cooperated in the murder,” Lamborn thundered. “But there is no legal evidence to convict him. Nor is there evidence to convict Captain Grover, although I verily believe he was at the jail with his gun.”

Then he sat down.

The defense table stirred uneasily. Their opponent had just surrendered the better part of his case. What would they do? With their clients’ lives hanging in the balance, they did their jobs. Three of them tore apart Lamborn and his evidence for the better part of a day and a half. Calvin Warren delivered an impassioned anti-Mormon philippic, strongly suggesting that whoever killed the Smiths had done society a favor. “If these men are guilty, then are every man, woman and child in the county guilty,” Warren said. “The same evidence . . . could have been given against hundreds of others. It was public opinion that the Smiths ought to be killed, and public opinion made the laws.”

On Thursday morning, Warren’s colleague Onias Skinner expatiated for three hours on the legal definition of a conspiracy, explaining how his clients’ actions amounted to nothing of the sort. By Thursday afternoon, there was nothing left for Browning to do but administer the coup de grâce to the state’s botched prosecution. He did so, brilliantly. “No human mind can doubt but Daniels has been bribed,” Browning told the jury. “He cares neither for God nor man.” Neither Daniels nor Brackenbury work for a living, Browning told the jury, eleven of whom were farmers. But they “fare sumptuously . . . fed by an unseen hand.” The uxorious Browning, who was very much in love with his pipe-smoking wife, Eliza, allowed that he attacked Eliza Graham’s account “with reluctance,” belonging as she does “to the gentler sex.” Then he eviscerated her testimony.

Other books

Overruled by Damon Root

High Water (1959) by Reeman, Douglas

Loving the Omega by Carrie Ann Ryan

A Vote of Confidence by Robin Lee Hatcher

White Teeth by Zadie Smith

Weight Till Christmas by Ruth Saberton

Isabella by Loretta Chase

The Alpine Menace by Mary Daheim

Lo que devora el tiempo by Andrew Hartley

Overdrive by Chloe Cole