Battle Cry of Freedom: The Civil War Era (135 page)

Read Battle Cry of Freedom: The Civil War Era Online

Authors: James M. McPherson

Tags: #General, #History, #United States, #Civil War Period (1850-1877), #United States - History - Civil War; 1861-1865, #United States - History - Civil War; 1861-1865 - Campaigns

But there was no point putting these men into Chattanooga when the

9

. Dennett,

Lincoln/Hay

, 106.

10

. George Edgar Turner,

Victory Rode the Rails

(Indianapolis, 1953), 288–94; Thomas Weber,

The Northern Railroads in the Civil War

(New York, 1952), 181–86. From first to last, the transfer of Longstreet's 12,000 infantry about 900 miles had required twelve days and the transportation of their artillery and horses an additional four days. Longstreet left his supply wagons and their horses behind in Virginia.

soldiers already there could not be fed. And there seemed to be no remedy for that problem without new leadership. In mid-October, Lincoln took the matter in hand. He created the Division of the Mississippi embracing the whole region between that river and the Appalachians, and put Grant in command "with his headquarters in the field."

11

The field just now was Chattanooga, so there Grant went. On the way he authorized the replacement of Rosecrans with Thomas as commander of the Army of the Cumberland. Within a week of Grant's arrival on October 23, Union forces had broken the rebel stranglehold on the road and river west of Chattanooga and opened a new supply route dubbed the "cracker line" by hungry bluecoats. Although Rosecrans's staff had planned the operation that accomplished this, it was Grant who ordered it done. A Union officer later recalled that when Grant came on the scene "we began to see things move. We felt that everything came from a plan."

12

The inspiration of Grant's presence seemed to extend even to the 11th Corps, which had suffered disgrace at Chancellorsville and Gettysburg but fought well during a night action October 28–29 to open the cracker line. By mid-November, Sherman had arrived with 17,000 troops from the Army of the Tennessee to supplement the 20,000 men Hooker had brought from the Army of the Potomac to reinforce the 35,000 infantry of Thomas's Army of the Cumberland. Though Bragg still held Lookout Mountain and Missionary Ridge, his immediate future began to look cloudy.

This cloudiness stemmed in part from continuing internecine warfare within Bragg's command. Soon after Chickamauga, Bragg suspended Polk and two other generals for slowness or refusal to obey crucial orders before and during the battle. The hot-blooded Forrest, bitter about failure to follow up the victory, refused to serve any longer under Bragg and returned to an independent command in Mississippi after telling Bragg to his face: "I have stood your meanness as long as I intend to. You have played the part of a damned scoundrel. . . . If you ever again try to interfere with me or cross my path it will be at the peril of your life." Several generals signed a petition to Davis asking for Bragg's removal. Longstreet wrote to the secretary of war with a lugubrious prediction that "nothing but the hand of God can save us or help us as long as we have our present commander."

13

Twice before—after Perryville and Stones River—similar dissensions

11

.

O.R.

, Ser. I, Vol. 30, pt. 4, p. 404.

12

. Bruce Catton,

Grant Takes Command

(Boston, 1969), 56.

13

. Henry,

"First with the Most" Forrest

, 199;

O.R.

, Ser. I, Vol. 30, pt. 4, p. 706.

had erupted in the Army of Tennessee. On October 6 a weary Jefferson Davis boarded a special train for the long trip to Bragg's headquarters where he hoped to straighten out the mess. In Bragg's presence all four corps commanders told Davis that the general must go. After this embarrassing meeting, Davis talked alone with Longstreet and may have sounded him out on the possibility of taking the command. But as a sojourner from Lee's army, Longstreet professed unwillingness and recommended Joseph Johnston. At this the president bridled, for he had no confidence in Johnston and considered him responsible for the loss of Vicksburg. Beauregard was another possibility for the post. Although he was then doing a good job holding off Union attacks on Charleston, Davis had tried Beauregard once before as commander of the Army of Tennessee and found him wanting. In the end there seemed no alternative but to retain Bragg. In an attempt to reduce friction within the army, Davis authorized the transfer of several generals to other theaters. He also counseled Bragg to detach Longstreet with 15,000 men for a campaign to recapture Knoxville—an ill-fated venture that accomplished nothing while depriving Bragg of more than a quarter of his strength. Indeed, none of Davis's decisions during this maladroit visit had a happy result. The president left behind a sullen army as he returned to Richmond.

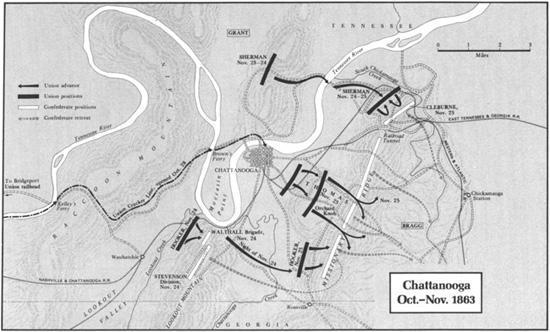

With Longstreet's departure in early November the Confederates yielded the initiative to Grant. As soon as Sherman's reinforcements arrived, Grant set in motion a plan to drive the rebels away from Chattanooga and open the gate to Georgia. As usual the taciturn general's offensive succeeded, but this time not in quite the way he had planned. Grant rejected the idea of a frontal assault against the triple line of trenches on Missionary Ridge as suicidal. He intended to attack both ends of Bragg's line to get on the enemy's flanks. Believing that Thomas's Army of the Cumberland was still demoralized from their shock at Chickamauga and "could not be got out of their trenches to assume the offensive," Grant assigned them the secondary role of merely threatening the Confederate center on Missionary Ridge while Sherman's and Hooker's interlopers from the Armies of the Tennessee and the Potomac did the real fighting on the flanks.

14

By this plan Grant unwittingly applied a goad to Thomas's troops that would produce a spectacular though serendipitous success.

Hooker carried out the first part of his job with a flair. On November

14

.

Memoirs of General William T. Sherman

, 2 vols. (2nd ed., New York, 1886), I, 390.

24 he sent the better part of three divisions against three Confederate brigades holding the northern slope of Lookout Mountain. The Yankee infantry scrambled uphill over boulders and fallen trees through an intermittent fog that in later years became romanticized as the "Battle Above the Clouds." With surprisingly light casualties (fewer than 500), Hooker's troops drove the rebels down the reverse slope, forcing Bragg that night to evacuate his defenses on Lookout and pull the survivors back to Missionary Ridge.

During the night the skies cleared to reveal a total eclipse of the moon; next morning a Kentucky Union regiment clawed its way to Lookout's highest point and raised a huge American flag in sunlit view of both armies below. For the South these were ill omens, though at first it did not appear so. On the other end of the line Sherman had found the going hard. When his four divisions pressed forward on November 24 they quickly took their assigned hill at the north end of Missionary Ridge—but found that it was not part of the ridge at all, but a detached spur separated by a rock-strewn ravine from the main spine. The latter they attacked with a will on the morning of November 25 but were repeatedly repulsed by Irish-born Patrick Cleburne's oversize division, the best in Bragg's army. Meanwhile Hooker's advance toward the opposite end of Missionary Ridge was delayed by obstructed roads and a wrecked bridge.

His plan not working, Grant in mid-afternoon ordered Thomas to launch a limited assault against the first line of Confederate trenches in the center to prevent Bragg from sending reinforcements to Cleburne. Thomas made the most of this opportunity to redeem his army's reputation. He sent four divisions, 23,000 men covering a two-mile front, across an open plain straight at the Confederate line. It looked like a reprise of Pickett's charge at Gettysburg, with blue and gray having switched roles. And this assault seemed even more hopeless than Pickett's, for the rebels had had two months to dig in and Missionary Ridge was much higher and more rugged than Cemetery Ridge. Yet the Yankees swept over the first line of trenches with astonishing ease, driving the demoralized defenders pell-mell up the hill to the second and third lines at the middle and top of the crest.

Having accomplished their assignment, Thomas's soldiers did not stop and await orders. For one thing, they were now sitting ducks for the enemy firing at them from above. For another, these men had something to prove to the rebels in front of them and to the Yankees on their flanks. So they started up the steep ridge, first by platoons and companies,

then by regiments and brigades. Soon sixty regimental flags seemed to be racing each other to the top. At his command post a mile in the rear, Grant watched with bewilderment. "Thomas, who ordered those men up the ridge?" he asked angrily. "I don't know," replied Thomas. "I did not." Someone would catch hell if this turned out badly, Grant muttered as he clamped his teeth on a cigar. But he need not have worried. Things turned out better than anyone at Union headquarters could have expected—the miracle at Missionary Ridge, some of them were calling it by sundown. To the Confederates it seemed a nightmare. As the Yankees kept coming up the hill the rebels gaped with amazement, panicked, broke, and fled. "Completely and frantically drunk with excitement," blueclad soldiers yelled "Chickamauga! Chickamauga!" in derisive triumph at the backs of the disappearing enemy. Darkness and a determined rear-guard defense by Cleburne's division, which had not broken, prevented effective pursuit. But Bragg's army did not stop and regroup until it had retreated thirty miles down the railroad toward Atlanta.

15

Union soldiers could hardly believe their stunning success. When a student of the battle later commented to Grant that southern generals had considered their position impregnable, Grant replied with a wry smile: "Well, it

was

impregnable." Bragg himself wrote that "no satisfactory excuse can possibly be given for the shameful conduct of our troops. . . . The position was one which ought to have been held by a line of skirmishers."

16

But explanations if not excuses can be offered. Some Confederate regiments at the base of Missionary Ridge had orders to fall back after firing two volleys; others had received no such orders. When the latter saw their fellows apparently breaking to the rear, they were infected by panic and began running. The Union attackers followed the retreating rebels so closely that Confederates in the next line had to hold their fire to avoid hitting their own men. As northern soldiers climbed the slope, they used dips and swells in the ground for cover against enemy fire from the line at the top, which Bragg's engineers had mistakenly located along the

topographical

crest rather than

15

. Quotations from Joseph S. Fullerton, "The Army of the Cumberland at Chattanooga,"

Battles and Leaders

, III, 725, and James A. Connolly,

Three Years in the Army of the Cumberland

, ed. Paul M. Angle (Bloomington, 1959), 158.

16

. Ulysses S. Grant, "Chattanooga,"

Battles and Leaders

, III, 693n; Bragg's official report in

O.R.

, Ser. I, Vol. 31, pt. 2, p. 666.

the

military

crest where the line of fire would not be blocked by such dips and swells. Perhaps the ultimate explanation, however, was the Army of Tennessee's dispirited morale which had spread downward from backbiting generals to the ranks. Bragg conceded as much in a private letter to Jefferson Davis tendering his resignation. "The disaster admits of no palliation," he wrote. "I fear we both erred in the conclusion for me to retain command here after the clamor raised against me."

17

As the army went into winter quarters, Davis grasped the nettle and grudgingly appointed Johnston to the command.

Meanwhile the repulse on November 29 of Longstreet's attack against Knoxville deepened Confederate woes. In Virginia a campaign of maneuver by Lee after the 11th and 12th Corps left the Army of the Potomac also turned out badly. During October, Lee tried to turn the Union right and get between Meade and Washington. Having foiled that move, Meade in November attempted to turn Lee's right on the Rapidan. Though unsuccessful, the Federals inflicted twice as many casualties as they suffered during these maneuvers, subtracting another 4,000 men from the Army of Northern Virginia it could ill afford to lose.