Battle Cry of Freedom: The Civil War Era (85 page)

Read Battle Cry of Freedom: The Civil War Era Online

Authors: James M. McPherson

Tags: #General, #History, #United States, #Civil War Period (1850-1877), #United States - History - Civil War; 1861-1865, #United States - History - Civil War; 1861-1865 - Campaigns

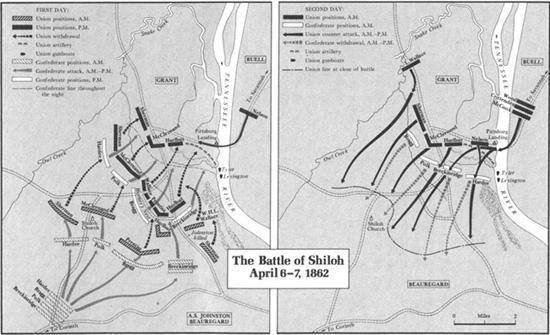

For thousands of them the shock of "seeing the elephant" (the contemporary expression for experiencing combat) was too much. They fled to the rear and cowered under the bluffs at the landing. Fortunately for the Union side, thousands of southern boys also ran from the front with terror in their eyes. One of the main tasks of commanders on both sides was to reorganize their shattered brigades and plug holes caused by this leakage to the rear and mounting casualties. Grant visited each of his division commanders during the day and established a line of reorganized stragglers and of artillery along the ridge west of Pittsburg Landing to make a last-ditch stand if the rebels got that far. Johnston went personally to the front on the Confederate right to rally exhausted troops by his presence. There in midafternoon he was hit in the leg by a bullet that severed an artery and caused him to bleed to death almost before he realized he had been wounded.

Beauregard took command and tried to keep up the momentum of the attack. By this time the plucky southerners had driven back the Union right and left two miles from their starting point. In the center, though, Prentiss with the remaining fragments of his division and parts of two others had formed a hard knot of resistance along a country lane that northern soldiers called the sunken road and rebels called the hornets' nest. Grant had ordered Prentiss to "maintain that position at all hazards."

21

Prentiss obeyed the order literally. Instead of containing and bypassing this position (a tactical maneuver not yet developed), southern commanders launched a dozen separate assaults against it. Although 18,000 Confederates closed in on Prentiss's 4,500 men, the uncoordinated nature of rebel attacks enabled the Yankees to repel each of them. The southerners finally pounded the hornets' nest with sixty-two field guns and surrounded it with infantry. Prentiss surrendered his 2,200 survivors at 5:30, an hour before sunset. Their gritty stand had bought time for Grant to post the remainder of his army along the Pittsburg Landing ridge.

By then, Lew Wallace's lost division was arriving and Buell's lead brigade was crossing the river. Beauregard did not know this yet, but he sensed that his own army was disorganized and fought out. He therefore refused to authorize a final assault in the gathering twilight. Although partisans in the endless postwar postmortems in the South condemned this decision, it was a sensible one. The Union defenders had the advantages of terrain (many of the troops in a Confederate assault would have had to cross a steep backwater ravine) and of a large concentration of artillery—including the eight-inch shells of two gunboats. With the arrival of reinforcements, Yankees also gained the advantage of numbers. On the morrow Buell and Grant would be able to put 25,000 fresh troops into action alongside 15,000 battered but willing survivors who had fought the first day. Casualties and straggling had reduced the number of Beauregard's effectives to about 25,000. Sensing this, Grant never wavered in his determination to counterattack on April 7. When some of his officers advised retreat before the rebels could renew their assault in the morning, Grant replied: "Retreat? No. I propose to attack at daylight and whip them."

22

21

.

Ibid

., p. 279.

22

. Bruce Catton,

Grant Moves South

(Boston, 1960), 241.

Across the lines Beauregard and his men were equally confident. Beauregard sent a victory telegram to Richmond: "After a severe battle of ten hours, thanks be to the Almighty, [we] gained a complete victory, driving the enemy from every position." Tomorrow's task would be simply one of mopping up. If Beauregard had been aware of Grant's reinforcements he would not have been so confident. But the rebel high command had been misled by a report from cavalry in northern Alabama that Buell was heading that way. Cavalry nearer at hand could have told him differently. Nathan Bedford Forrest's scouts watched boats ferry Buell's brigades across the river all through the night. Forrest tried to find Beauregard. Failing in this, he gave up in disgust when other southern generals paid no attention to his warnings. "We'll be whipped like Hell" in the morning, he predicted.

23

Soldiers on both sides passed a miserable night. Rain began falling and soon came down in torrents on the 95,000 living and 2,000 dead men scattered over twelve square miles from Pittsburgh Landing back to Shiloh church. Ten thousand of the living were wounded, many of them lying in agony amid the downpour. Lightning and thunder alternated with the explosions of shells lobbed by the gunboats all night long into Confederate bivouacs. Despite their exhaustion, few soldiers slept on this "night so long, so hideous." One Union officer wrote that his men, "lying in the water and mud, were as weary in the morning as they had been the evening before."

24

Grant spent the night on the field with his men, declining the comfort of a steamboat cabin. Four miles away Beauregard slept comfortably in Sherman's captured tent near Shiloh church. Next morning he had a rude awakening. A second day at Shiloh began with a surprise attack, but now the Yankees were doing the attacking. All along the line Buell's Army of the Ohio and Grant's Army of Western Tennessee swept forward, encountering little resistance at first from the disorganized rebels. In mid-morning the southern line stiffened, and for a few hours the conflict raged as hotly as on the previous day. A particularly unnerving sight to advancing Union troops was yesterday's casualties. Some wounded men had huddled together for warmth during the night. "Many had died there, and others were in the last agonies as we passed," wrote a northern soldier. "Their groans and cries were heart-rending. . . . The

23

.

O.R

., Ser. I, Vol. 10, pt. 1, p. 384; Robert S. Henry, "

First with the Most" Forrest

(Indianapolis, 1944), 79.

24

. McDonough,

Shiloh

, 189, 188.

gory corpses lying all about us, in every imaginable attitude, and slain by an inconceivable variety of wounds, were shocking to behold."

25

By midafternoon the relentless Union advance had pressed the rebels back to the point of their original attack. Not only did the Yankees have fresh troops and more men, but the southerners' morale had suffered a letdown when they realized they had not won a victory after all. About 2:30 Beauregard's chief of staff said to the general: "Do you not think our troops are very much in the condition of a lump of sugar thoroughly soaked with water, but yet preserving its original shape, though ready to dissolve? Would it not be judicious to get away with what we have?"

26

Beauregard agreed, and issued the order to retreat. The blue-coats, too fought out and shot up for effective pursuit over muddy roads churned into ooze by yet another downpour, flopped down in exhaustion at the recaptured camps. Next day Sherman did take two tired brigades in pursuit four miles down the Corinth road, but returned after a brief skirmish with Forrest's cavalry that accomplished little more than the wounding of Forrest. Both the blue and the gray had had enough fighting for a while.

And little wonder. Coming at the end of a year of war, Shiloh was the first battle on a scale that became commonplace during the next three years. The 20,000 killed and wounded at Shiloh (about equally distributed between the two sides) were nearly double the 12,000 battle casualties at Manassas, Wilson's Creek, Fort Donelson, and Pea Ridge

combined

. Gone was the romantic innocence of Rebs and Yanks who had marched off to war in 1861. "I never realized the 'pomp and circumstance' of the thing called glorious war until I saw this," wrote a Tennessee private after the battle. "Men . . . lying in every conceivable position; the dead . . . with their eyes wide open, the wounded begging piteously for help. . . . I seemed . . . in a sort of daze." Sherman described "piles of dead soldiers' mangled bodies . . . without heads and legs. . . . The scenes on this field would have cured anybody of war."

27

Shiloh disabused Yankees of their notion of a quick Confederate collapse in the West. After the surrender of Donelson, a Union soldier had

25

.

Ibid

., 204.

26

. Thomas Jordan, "Notes of a Confederate Staff-Officer at Shiloh,"

Battles and Leaders

, I, 603.

27

. McDonough,

Shiloh

, 4–5; Mark A. DeWolfe Howe, ed.,

Home Letters of General Sherman

(New York, 1909), 222–23.

written: "My opinion is that this war will be closed in less than six months." After Shiloh he wrote: "If my life is spared I will continue in my country's service until this rebellion is put down, should it be ten years." Before Shiloh, Grant had believed that one more Union victory would end the rebellion; now he "gave up all idea of saving the Union except by complete conquest."

28

Shiloh launched the country onto the floodtide of total war.

III

Although Grant had snatched victory from the jaws of defeat at Pittsburg Landing, northern opinion at first focused more on those jaws than on victory. Newspapers reported Union soldiers bayoneted in their tents and Grant's army cut to pieces before being saved by the timely arrival of Buell. A hero after Donelson, Grant was now a bigger goat than Albert Sidney Johnston had been in the South after his retreat from Tennessee. What accounted for this fickleness of northern opinion? The reverses of the first day at Shiloh and the appalling casualties furnish part of the explanation. The self-serving accounts by some of Buell's officers, who talked more freely to reporters than did Grant and his subordinates, also swayed opinion. False rumors circulated that Grant was drunk at Shiloh. The disgraced captain of 1854 seemed unable to live down his reputation. Then, too, the magnitude of northern victory at Shiloh was not at first apparent. Indeed, Beauregard persevered in describing the battle as a southern triumph. Only "untoward events," he reported, had saved the Yankees from annihilation; the Confederate withdrawal to Corinth was part of a broader strategic plan!

29

When the recognition of Confederate failure at Shiloh finally sank in, many southerners turned against Beauregard. They blamed him for having snatched defeat from the jaws of victory by refusing to order a final twilight assault on the first day. About the time this shift occurred in southern opinion, Illinoisians began coming to Grant's defense. When a prominent Pennsylvania Republican went to Lincoln and said that Grant was incompetent, a drunkard, and a political liability to the administration, the president heard him out and replied: "

I can't spare this man; he fights."

One of Grant's staff officers furnished Illinois Congressman

28

. Albert Dillahunty,

Shiloh National Military Park, Tennessee

(National Park Service Historical Handbook Series No. 10, Washington, 1955), 1; Grant,

Memoirs

, I, 368.

29

. McDonough,

Shiloh

, 218.

Elihu Washburne, Grant's original sponsor, with information that prompted Washburne to extol Grant in a House speech as a general whose "almost superhuman efforts" at Shiloh had "won one of the most brilliant victories" in American history.

30

Washburne put the case too strongly. Grant made mistakes before the battle that all of his undoubted coolness and indomitable will during the fighting barely redeemed. But in the end the Union armies won a strategic success of great importance at Shiloh. They turned back the Confederacy's supreme bid to regain the initiative in the Mississippi Valley. From then on it was all downhill for the South in this crucial region. On the very day, April 7, that Beauregard's battered army began its weary retreat to Corinth, a Union army-navy team won another important—and almost bloodless—triumph on the Mississippi.