Blood Brotherhoods (117 page)

Read Blood Brotherhoods Online

Authors: John Dickie

Periodically, throughout the early years of the twenty-first century, Campania’s broken-down garbage-disposal system seized up entirely. At the worst point in 2007–8, hundreds of thousands of tonnes of waste from homes and shops accumulated in the streets. The authorities responded by

forcibly reopening rubbish dumps that had already been deemed to be full. Local people, justifiably worried about the impact on their quality of life, staged angry protests. News cameras from around the world relayed the pictures of both the trash-mountains and the protests, causing untold damage to the reputation of Naples, Campania and Italy. Only in the last couple of years have the authorities begun to get a grip on the situation, it seems, although many piles of ecobales remain to scar the landscape.

The

monnezza

scandal (named after the Neapolitan for garbage) is still subject to legal proceedings: a number of politicians, entrepreneurs and administrators have been charged with fraud or negligence. Irrespective of the precise criminal blame, the story is one of shambolic politics, irresponsible business (including northern business), bad planning, mismanagement, and inadequate monitoring. The problems started at the top: the Commissariat supposed to keep tabs on the whole system stands accused of cronyism and inflated expenses as well as a manifest failure to make sure that the rubbish cycle actually worked.

The

monnezza

affair bears many similarities to the chaos of reconstruction following the 1980 earthquake. For one thing, both of them created opportunities for organised crime. The camorra was late to enter the construction industry when compared to Cosa Nostra and the ’ndrangheta. While Sicilian gangsters were heavily involved in the building boom of the 1950s and 1960s, and the Calabrians followed suit in the 1960s and 1970s, only following the 1980 earthquake did

camorristi

start earning serious money from concrete. But when it came to rubbish, the camorra clans became pioneers and protagonists. ‘Eco-mafia’ is a term coined by Italian environmentalists to refer to the damage the underworld inflicts on Italy’s natural and other resources—from illegal building to the traffic in architectural treasures. The waste sector is the most lucrative eco-mafia activity, and one of the biggest growth areas in criminal enterprise in the last two decades.

As with construction, the camorra infiltrated the rubbish system in a variety of ways, starting with the eighteen consortia set up to manage recycling in different parts of the region. Many of the people employed in these consortia were drawn from militant lobby groups of unemployed people. Some of those lobby groups, which date back to the 1970s, have been linked to the camorra: their leaders have been shown to have extracted bribes from members in return for the promise of a job; quite a few of the members have criminal records. In 2004, the regional rubbish Commissar told a parliamentary inquiry that: ‘It’s a miracle even if 200 of the 2,316 people [employed by the recycling consortia] actually do any work.’ It is estimated that, by the end of 2007, more than forty of the lorries bought to transport recycled rubbish had been stolen.

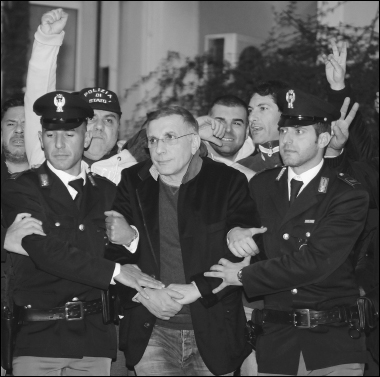

Cash from trash. Shocking mismanagement of the rubbish system created lucrative opportunities for the camorra, Naples, 2008.

The camorra also moved in on the subcontracts and sub-subcontracts handed out for moving the ecobales around. Since the days of the post-earthquake construction boom, the camorra has had a near-monopoly on earth-moving. There is evidence of camorra profiteering on the deals that were rushed through to buy land where ecobales could be stored.

In some places, notably around Chiaiano, young

camorristi

took control of the protests against reopening old garbage dumps. Inevitably, the demonstrations turned violent. There were probably two reasons why the camorra became involved. First, because their bosses had an economic interest in perpetuating the emergency. And second, because they wanted to pose as community leaders, champions of NIMBYism. Much of the trouble was concentrated at a dump not far from Marano, the base of the Nuvoletta clan. A banner was hoisted above the entrance to the town: ‘The state is absent, but we are here’. Nobody needed to be told who this ‘we’ was.

Mondragone, the buffalo-milk mozzarella capital on the northern coast of Campania, was the base for a waste-management company called Eco4 that was at the centre of a thoroughgoing infiltration of the rubbish cycle by the clans: an illicit circuit of votes, jobs, inflated invoices, rigged contracts and bribes tied together politicians, administrators, entrepreneurs and

camorristi

. In the summer of 2007, one of the Eco4 directors implicated in

the case, Michele Orsi, started to give evidence to magistrates. The following May he went out with his young daughter to buy a bottle of Coca-Cola and was shot eighteen times. Other witnesses in the Eco4 case implicated a senior politician close to Silvio Berlusconi. In 2009, Nicola Cosentino was both Junior Minister for Finance and the coordinator of Berlusconi’s party in the Campania region when magistrates asked parliament for authorisation to proceed against him for working with the camorra. Berlusconi’s governing majority turned down the request. The following year parliament refused to give investigators permission to use phone-tap evidence against Cosentino, although he did resign from his government job later that year when he was involved in another scandal. In January 2012 parliament again sheltered him from arrest under camorra-related charges. Cosentino claimed that he was the victim of ‘media, political and judicial aggression’.

However, by far the most worrying aspect of eco-mafia crime in Campania is not directly related to the rubbish emergency and the ecobales affair. In the early 1990s, evidence began to emerge that

camorristi

were illegally dumping millions of tonnes of toxic waste from hospitals and a variety of industries such as steel, paint, fertiliser, leather and plastics. The poisons found to be involved included asbestos, arsenic, lead and cadmium. The picture was confirmed by the investigation known as Operation Cassiopea between 1999 and 2003. Although the camorra’s trucks transported and dumped the waste in Campania, they were only the end point of a national system. Agents for camorra-backed waste-management firms toured the north and centre of the country, offering to make companies’ dangerous by-products vanish for as little as a tenth of the cost of legal disposal. Obliging politicians and bureaucrats along the toxic-waste route made sure that the paperwork was in order. The

camorristi

tipped the waste anywhere and everywhere in the territory they controlled, ranging from ordinary municipal dumps to roadside ditches. Some of the toxic waste was blended with other substances to make ‘compost’. In many cases the waste was placed on top of a layer of car tyres and burned to destroy the evidence, thus poisoning the air as well as the soil and the water table. The camorra also dumped toxic waste into the quarries situated in the hillier parts of the Terra di Lavoro, from which they extracted the sand and gravel for their concrete plants. Many of these quarries were also illegal. In 2005, a judge described the disappearance of whole mountains in what he called a ‘meteorite effect’. Hence the harm from one eco-mafia crime was multiplied by that from another.

The profits of this trade were enormous. One toxic-waste dealer who turned state’s evidence handed over a property portfolio that included forty-five apartments and a hotel, to a total value of $65 million.

Many of those charged in the trial that resulted from the Cassiopea investigation confessed. Despite that, in September 2011, a judge decided not to carry on with the case because inordinate delays in procedure meant that the crimes would inevitably have fallen under Italy’s statute of limitations: according to Italian law, it all happened too long ago for guilty verdicts to be reached. The toxic waste strewn across the Terra di Lavoro recognises no such time restrictions. Generations of citizens living on this sullied land will pay the price for what the magistrate in charge of the Cassiopea investigation called an ‘Italian Chernobyl’.

G

OMORRAH

T

HE PEAK OF THE

N

APLES RUBBISH CRISIS IN

2007–8

COINCIDED WITH THE STARTLING

success of a book that has made the camorra better known around the world than it has been since before the First World War.

Gomorrah

(the title is a pun) was published in 2006 by a little-known twenty-six-year-old writer and journalist called Roberto Saviano.

Before

Gomorrah

, the fragmented camorra had once more become the subject of bewildered indifference outside Campania. Reporters who tried to keep the public informed about outbreaks of savagery like the Scampia Blood Feud found that the faces, names and underworld connections proliferated far beyond the tolerance of even the most dogged lay reader.

Gomorrah

is, at first glance, an unlikely book to have reawoken public concern about the apparent chaos in Campania. It is a hybrid: a series of unsettling essays that are part autobiography, part undercover reportage, part political polemic, part history. Compelling as they are, none of these ingredients holds

Gomorrah

together. The secret of its remorseless grip on Italian readers resides in the way Saviano puts his own sensibility at the centre of the story. His is a kaleidoscopic and immediate personal testimony rooted in a visceral rage and revulsion. He is not content to observe the holes punched in bulletproof glass by an AK-47; he is morbidly drawn to rub his finger against the edges until it bleeds. He feels the salty swill of nausea rise in his throat as yet another teenage hoodlum is scooped into a body bag from a pool of gore in the street during the Scampia Blood Feud. Anger clutches at his chest like asthma when the umpteenth building worker dies

on an illegal construction site. The ground seethes beneath him as he explores a landscape contaminated for decades by illegally dumped carcinogens.

Saviano had every right to make his own feelings so important to his account of the camorra (or ‘the System’, as he taught Italians to call it). For he hails from Casal di Principe, in the heart of the most notorious part of the Terra di Lavoro. After the eclipse of Carmine ‘Mr Angry’ Alfieri in 1992, the local clan, the

casalesi

, became the dominant force in the camorra. The core group of

casalesi

were a highly proficient team of killers deployed against the Nuova Camorra Organizzata in the 1980s—the ‘Israelis’ to the Professor’s ‘Arabs’. The group evolved into a federation of four criminal families. In 1988, the

casalesi

did away with their own boss, Antonio Bardellino. After a bloody civil war, they were able to take over his concrete and cocaine interests. They also branched into agricultural fraud and buffalo-milk mozzarella. The

casalesi

established a local monopoly on the distribution of some major food brands. Moreover, the Eco4 waste-management business was one of their front companies. The

casalesi

were also the clan responsible for creating the ‘Italian Chernobyl’ on their own territory with their traffic in toxic refuse. According to a penitent from the

casalesi

, when one of the clan’s affiliates expressed doubts to his boss, he received a dismissive reply: ‘Who gives a toss if we pollute the water table? We drink mineral water anyway.’

By September 2006,

Gomorrah

had already won prizes as well as tens of thousands of readers, particularly among the young. At that point Saviano returned to his home town to take part in a demonstration in favour of the rule of law. Speaking in the piazza from a raised table in front of an azure backcloth, he was moved to call out to the bosses by name: ‘Iovine, Schiavone, Zagaria—you aren’t worth a thing!’ He then addressed the crowd: ‘Their power rests on your fear! They must leave this land!’ No one should underestimate the bravery of these words: as Saviano knew, relatives of

casalesi

bosses were watching him from the piazza.

Within days, the authorities received intimations of what was to be the first of several credible threats against Saviano’s life. Ever since then, he has lived under armed escort. Gratifyingly, his predicament boosted sales: the latest estimates are that

Gomorrah

has sold well over two million copies in Italy, and has been translated into fifty-two languages. In 2008, a film dramatisation of

Gomorrah

—which in my view is even better than the book—won the Grand Prize at the Cannes Film Festival and went on to bring Saviano’s vision to a bigger audience still.

Gomorrah

’s author is now a major celebrity: millions tune in to watch his televised lectures, and his articles reliably boost the circulation of the newspapers that host them.