Blood Brotherhoods (51 page)

Read Blood Brotherhoods Online

Authors: John Dickie

The Inspectorate were well aware that the men Dr Allegra called brothers were in a permanent state of war among themselves, whether open or declared. The mafia was prone to ‘internecine struggles deriving from grudges which, whether they were recent and remote, nearly always revolved around who was to gain supremacy when it came to distributing the various positions within the organisation’. An ‘internecine struggle’ of just this kind would give the Inspectorate its route into the mafia’s very nucleus, the lemon groves of the Conca d’Oro around Palermo.

When the Iron Prefect first came to Palermo in October 1925, his attention was immediately drawn to the Piana dei Colli, the northern part of the Conca d’Oro where Inspector Ermanno Sangiorgi first tussled with the mafia in the 1870s. Half a century later, the Piana dei Colli was the site of a particularly ferocious battle between two mafia factions. The conflict left bodies in the streets of central Palermo, many of them belonging to senior bosses. Some of the mafia dynasties that had ruled the area since the 1860s did not survive the carnage. Those that did, and who didn’t manage to escape to America, Tunisia or London, were rounded up by the Iron Prefect’s cops. Then Mori left, and calm returned.

The Inspectorate discovered that the

mafiosi

from the Piana dei Colli who had been released, or returned from exile after the Mori Operation ended, could not reorganise their Families because of the residual tensions between them. The tit-for-tat killings resumed. In 1934, a boss named Rosario Napoli was slain; the culprits tried to frame Napoli’s own nephew for the murder. This nephew was the first Palermitan

mafioso

to give information to the Inspectorate. His testimony slowly tipped into a cascade of confessions from other mobsters, some of whom described the initiation ritual they had undergone when they were first admitted. As so often,

omertà

had cracked. By bringing together these confessions, and patiently corroborating them, the Inspectorate then assembled a narrative of the war in the Conca d’Oro that shed an even more withering light on Mussolini’s portentous Ascension Day claims.

The protagonists of this new narrative were the Marasà brothers, Francesco, Antonino, and above all Ernesto—the

generalissimo

, as the Inspectorate dubbed him. The Marasà brothers had their power base in the western section of the Conca d’Oro, between Monreale and Porta Nuova. That is, along the road travelled by Turi Miceli and his mafia squad when they launched the Palermo revolt back in September 1866. Like Turi Miceli, the Marasà brothers had money. In fact the Inspectorate estimated that they owned property, livestock and other assets worth ‘quite a few million lire’. One million lire was worth some $52,000 at the time, and that amount in 1938 had the purchasing power of some $1.7 million today.

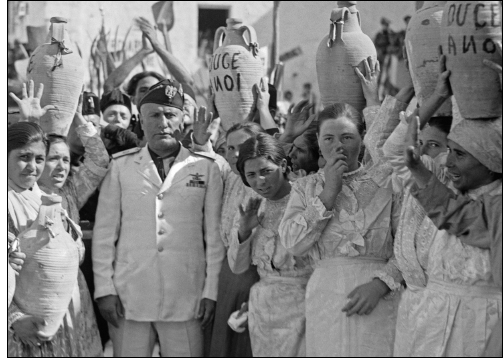

After the mafia’s defeat, 1937: Mussolini makes a triumphal visit to Sicily to open a new aqueduct. By this time the island’s criminal Families had returned to full operation under the leadership of Ernesto ‘the

generalissimo

’ Marasà.

What the men of the Inspectorate found most disturbing about the Marasà brothers was their ability to collect friendships among the island’s ruling class, to place themselves above suspicion, to cloak the power they had won through violence, and to cover the bloody tracks that traced their ascent.

By poisoning the political system under the pre-Fascist governments, they carried out their shady criminal business on the agricultural estates, in the lemon groves, in the city, in the suburban townships, in the villages. They always managed to stay hidden in the shadows cast by baronial and princely coats of arms, by medals and titles. Thanks to the shameful complaisance shown by men who are supposed to be responsible for the fair and efficient administration of the law, they always slipped away from punishment. But behind the politician’s mask, behind the honorific title, behind the all-pervasive hypocrisy and the imposing wealth, there lurked the coarsest kind of criminal, with evil, grasping instincts, whose warlike early years in the ranks of the underworld have left an indelible mark of infamy.

It is a testament to the Marasà brothers’ success in shrouding their ‘indelible mark of infamy’ that, until the discovery of the Inspectorate’s report in 2007, their names had hardly been mentioned in the chronicles of mafia history. No photographs, no police descriptions, hardly even any rumours: a criminal power all the more pervasive for being unseen and unnamed.

In the late 1920s, while the bosses of the Piana dei Colli were busy ambushing one another, and then falling victim to the Mori Operation, Ernesto Marasà and his brothers remained entirely untouched. Indeed,

generalissimo

Ernesto showed a breathtaking Machiavellian composure in the face of the Fascist onslaught: he actually fed incriminating information about his mafia rivals to the Iron Prefect’s investigators. Mussolini’s Fascist scalpel had been partially guided by a

mafioso

’s hand.

Ernesto Marasà’s rise to power continued after the Mori Operation ended. While his enemies were held in jail, seething about being betrayed, Marasà constructed an alliance of supporters across the mafia Families of Palermo’s entire hinterland, including the Piana dei Colli where he continued to undermine his enemies by passing information to the police. His plan was, quite simply, to become the mafia’s boss of all bosses. The Inspectorate spied on the

generalissimo

as he ran his campaign from room 2 of the Hotel Vittoria just off via Maqueda, Palermo’s main artery. Now and again, he and two or three of his heavies would clamber aboard a little red FIAT

Balilla

and set off to meet friends and arrange hits in one of Palermo’s many mafia-dominated

borgate

.

After five years of work, the Inspectorate could conclude its 1938 report with a chillingly clear description of the mafia’s structure that reads like a line-by-line demolition of the Iron Prefect’s own views.

The mafia is not just a state of mind or a mental habit. It actually spreads this state of mind, this mental habit, from within what is a genuine organisation. It is divided into so-called ‘Families’, which are sub-divided into ‘Tens’, and it has ‘bosses’ or ‘representatives’ who are formally elected. The members, or ‘brothers’, have to go through an oath to prove their unquestioning fidelity and secretiveness.

The oath, no one will be surprised to learn, involved pricking the finger with a pin, dripping blood on a sacred image, and then burning the image in the hands while swearing loyalty until death.

The mafia was organised ‘in the form of a sect, along the lines of the Freemasons’. Its Families in each province had an overall ‘representative’ whose responsibilities included contacts with the organisation’s branches abroad, in the United States, France and Tunisia. The Families in the provinces of Trapani, Agrigento and Caltanissetta looked to Palermo for leadership at crucial times. The mafia, declared the Inspectorate, ‘had an organic and harmonious structure, regulated by clearly defined norms, and managed by people who were utterly beyond suspicion’. At the centre of the mafia web, there was a ‘boss of all bosses’ or ‘general president’:

generalissimo

Ernesto Marasà.

The Inspectorate’s 1938 report was sent in multiple copies to senior figures in the judiciary and law enforcement. The forty-eight brave men who put their names to the document were desperate for their sleuthing to make a real difference in Sicily. Their desperation was evident in an indignant, impassioned turn of phrase: in the lurid talk of a ‘slimy octopus’ (as if a beast as sophisticated as the mafia could ever have just one head); and also in the conclusion, which deliberately parroted the catchphrases of Mussolini’s Ascension Day speech. Somewhere, they hoped, their plea would meet the eyes of someone determined to make Fascism’s results match up to its battle cries: there must be ‘no holding back’ against an evil that was ‘dishonouring Sicily’; the state must once again wield the ‘scalpel’ against the mafia.

The passion and insight that went into the Inspectorate’s 1938 report makes its every word chilling, for two reasons. First, because it provides the earliest absolutely indisputable evidence that the Sicilian mafia was a single highly structured organisation that extended right across western Sicily. Terms like ‘Family’, ‘representative’, and ‘boss of all bosses’ had never appeared before in the historical record. Second, because many years would pass, and the lives of many brave police,

Carabinieri

and magistrates would be sacrificed, before the moment in 1992 when a diagram of the Sicilian mafia that was

identical

to the one assembled by the Inspectorate would finally be accepted as the truth within the Italian legal system.

But in 1938 there was not the slightest hope that the Fascist state would return to a war footing against organised crime. In fact the signs that Fascism would fail to beat the mafia were there to be seen all along. In the Iron Prefect’s refusal to believe that his enemy was an Honoured Society, for example. Or in his crass view of Sicilian psychology. Or in Fascism’s preference for bundling suspects off into enforced residence on penal colonies: no noise, and no judicial process. For, as anyone with a historical memory for anti-mafia measures would have known, fighting organised crime in this way was like fighting weeds in your garden by transplanting them into your greenhouse.

The many faces of ‘Iron Prefect’ Cesare Mori, who spearheaded Mussolini’s attack on the Sicilian mafia in the 1920s.

Man of action, and scourge of the mafia.

Fascist role model.

Wannabe socialite . . .