Blood Brotherhoods (59 page)

Read Blood Brotherhoods Online

Authors: John Dickie

‘For you, I am not

commendatore

,’ came the reply, as Vizzini waddled into the book-lined study and lowered his meaty frame onto the sofa. ‘Call me Uncle Calò.’

Uncle Calò’s tone was firm, but his manner open-hearted. He praised Lo Schiavo as a man of the law who had played hard but fair. The two men shook hands as a sign of mutual respect. Lo Schiavo tells us that, as he gazed at Uncle Calò, he was reminded of a picture from the past, from his first years as an anti-mafia magistrate in Sicily, when he first met a corpulent old mafia boss who always rode a white mare. He concluded his memories of Uncle Calò with good wishes for his successor within the mafia: ‘May his efforts be directed along the path of respect for the state’s laws, and of social improvement for all.’

Lo Schiavo’s account of the conversation between himself and don Calogero Vizzini is as heavily embroidered as any of his novels. But the meeting itself really happened. The reason for Uncle Calò’s visit was that he was caught up in a series of trials for the hand-grenade attack back in 1944. Only three days earlier, the Supreme Court had issued a guilty verdict against him. But the legal process was due to run on for a long time yet, and Uncle Calò knew that he would almost certainly die before he saw the inside of a jail. The real reason that he called in on Lo Schiavo may simply have been to say thank you. For the celebrated magistrate-novelist was involved in presenting the prosecution evidence at the Supreme Court. The suspicion lingers that, behind the scenes, he gave the mafia boss a helping hand with his case.

In today’s Italy, if any magistrate received a social call from a crime boss he would immediately be placed under investigation. But in the conservative world of Christian Democrat Italy, affairs between the Sicilian mafia and magistrates were conducted in a more friendly way. The state and the mafia formed a partnership, in the name of the law.

C

ALABRIA

: The last romantic bandit

W

HEN IT CAME TO ORGANISED CRIME

,

POST-WAR

I

TALY

’

S AMNESIA WAS AS DEEP AND

complex as the country’s geology: its layers were the accumulated deposits of incompetence and negligence; the pressures of collusion and political cynicism sculpted its elaborate folds. By the time the Second World War ended, this geology of forgetfulness had created one of its most striking formations in Calabria.

In 1945, Italy’s best-loved criminal lunatic returned to the land where he had made his name. Aged seventy, and now deemed harmless, Giuseppe Musolino, the ‘King of Aspromonte’, was transferred from a penal asylum in the north to a civil psychiatric hospital way down south in Calabria.

Musolino’s new home was an infernal place. Although it was a Fascistera building, it was already crumbling by the time the Fascist dictator’s battered corpse was swinging by its heels from the gantry of a Milanese petrol station. Bare, unsanitary and overcrowded, the psychiatric hospital’s rooms and corridors echoed with the gibbering and shrieking of afflicted souls. But in the late 1940s and early 1950s, before today’s encrustation of motorways and jerry-built apartments had sprouted around the Calabrian coast, the hospital did at least afford a lovely panorama: before it, the view down to the city of Reggio Calabria, across the Straits of Messina, and over towards Sicily; behind it, the wooded shoulders of Aspromonte—the ‘harsh mountain’ that had once been Musolino’s realm.

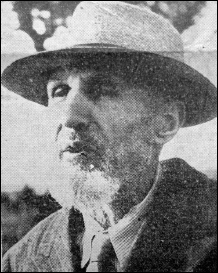

The new arrival attracted a great deal more attention and sympathy than the other patients. He was, after all, one of the most famous Calabrians alive. ‘Don Peppino’, the doctors and nurses all called him, combining a

respectful title and a fond nickname. Despite his mind’s desolation, his frail body did its best to live up to this lingering aura. Musolino was thin, but unbowed by decades of incarceration. His scraggy beard stood out strikingly white against the olive darkness of his skin, making him look part Athenian philosopher and part faun, as one journalist noted. An actress drawn to visit the hospital was struck breathless by his resemblance to Luigi Pirandello, the great Sicilian dramatist, whose tales of masks and madness had earned him a Nobel Prize.

Musolino’s own madness bore the blundering labels of mid-twentieth century psychiatry: ‘progressive chronic interpretative delirium’ and ‘pompous paranoia’. He thought he was the Emperor of the Universe. He spent most of his day outside, smoking, reading, and contemplating the shadow of the cypress trees in the nearby cemetery. Yet when he found anyone with the patience to talk, he would grasp the chance to expound the hierarchy over which he presided: from the kings, queens and princes enthroned at his feet, to the cops and stoolies who grovelled far below.

Don Peppino had an obsessive loathing of cops and stoolies. And somehow, when he spoke to visitors, that very loathing often became a pathway to the corners of his mind that were still lucid. ‘Bandits have to kill,’ he would concede, ‘but they must be honourable.’ For Musolino, honour meant vendetta: all the crimes that had led to his imprisonment had been carried out to avenge the wrong he had endured at the hands of the police and their informers. Even in his insanity, he prized honesty above all: he would proudly point out that he had never denied any of his murders. After all, the victims were only cops and stoolies.

The newspapermen who made the long journey to the mental hospital in Reggio relished the chance to delve into the past and fill the gaps in don Peppino’s fragmented memory for their readers. They told how this woodcutter’s son had escaped his wrongful imprisonment in 1899, and spent two and a half years as a renegade up in the Aspromonte massif. They told how he killed seven people and tried to kill six more, all the while proclaiming that he was the victim of an injustice. The longer he evaded capture, the more his reputation grew: he came to be seen as the ‘King of Aspromonte’, a wronged hero of the oppressed peasantry, a symbol of desperate resistance to a heartless state.

But the heartless state, the journalists explained, had its revenge in the end. During the years of solitary confinement that followed his capture, Musolino lost his mind. His insanity only threw his tragic stature into starker relief.

Then, in 1936, a Calabrian-born emigrant to the United States made a deathbed confession: it was he, and not Musolino, who had shot at Vincenzo Zoccali all those years ago. The King of Aspromonte had stuck heroically to the same story from the start of his murderous rampage, during his trial, and even through his descent into insanity. Now that story had been proved right.

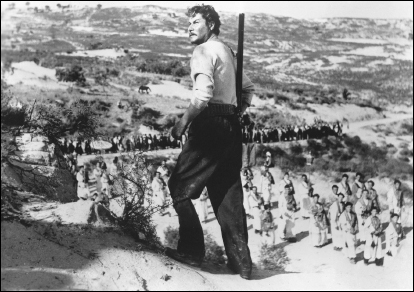

A noble and tragic desperado? Giuseppe Musolino was known as the ‘King of Aspromonte’. His famous story was acted out by major Italian star, Amedeo Nazzari, in the 1950 crime drama,

The Brigand Musolino

.

Perhaps it is no wonder that the psychiatrist in Reggio Calabria was so angry on his behalf. ‘Was Musolino antisocial?’ he asked in one newspaper interview. ‘Or was it society that forced him to become what he became?’

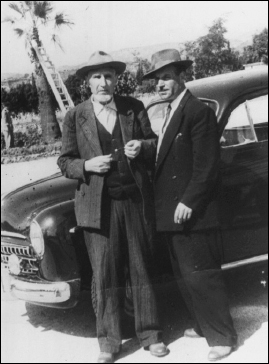

Don Peppino received many presents. The most generous—food, clothes and dollars—came from Calabrians who had emigrated to America and made it big. Occasionally, he was even allowed day release—when a sentimental Italian-American businessman in a fedora and pinstriped suit turned up to take the old bandit out on a motor tour of the mountain.

Looking back now, one has to suspect that the Americans who came to pay homage to Giuseppe Musolino may have known the truth. He was no lone bandit hero: he was a member of the Calabrian mafia, an Honoured Society killer. And the whole fable of the ‘King of Aspromonte’ had served only to keep what was really going on in Calabria hidden from the public eye.

After 1945, with the war over, the transition to democracy under way, and the King of Aspromonte residing in Reggio Calabria mental hospital, the organisation that is today known as the ’ndrangheta operated in very much the same way that it had done when he was in his murderous prime.

Carabinieri

‘co-managed’ petty crime with the underworld bosses. Grandees used the mafia to round up electors, and then returned the favour by

testifying in court that there was no such organisation. For successive governments, it proved easy to just bank the votes of Calabria’s mafia-backed members of parliament, and ignore the Honoured Society. And while politicians looked the other way, the police and magistracy had time to forget all they had learned about the Calabrian mafia during the Fascist era from—among other people—the King of Aspromonte’s own brother, Antonio Musolino. In the early 1920s, Antonio engaged in a long battle with his cousin and

capo

Francesco Filastò (the same cousin suspected of killing Lieutenant Joe Petrosino in 1909). In the end, defeated, impoverished and paralysed (a revolver shot cost him the use of his left leg and arm), Antonio Musolino went over to the state. He told the authorities everything he knew about the criminal organisation to which he, like his infamous brother, belonged. In 1932, his evidence fed into the trial of ninety men. Prosecutors in the 1932 case believed that the Calabrian mafia had its own governing body, known as the

Gran Criminale

(the Great Criminal), which intervened to settle disputes within the various

’ndrine

across the province of Reggio Calabria—but which had failed to settle the dispute between Antonio Musolino and his cousin. The surviving evidence suggests that the Great Criminal served the same purposes as what is now called the Crime, which would only finally be revealed to the world by investigators in 2010. In other words, post-war amnesia may well have cost Italy eighty wasted years when it came to understanding the unitary structure of Calabria’s Honoured Society.

Meanwhile, the real Musolino lived out his last years in a Reggio Calabria mental hospital.

Meanwhile, just as during Giuseppe Musolino’s homicidal rampage, lazy journalists were content to churn out the King of Aspromonte fable, even now that their primary source was a crazy geriatric killer. Musolino, for his part, lived as the Emperor of the Universe, commanding interplanetary

ships and deploying devices more destructive than the atomic bomb. In his psychologically damaged state, he became a metaphor for Italy’s own cognitive failure. The reasons for that failure were ultimately very simple. In southern Calabria, the conflict between Left and Right had nowhere near the explosiveness that propelled Sicily up the political agenda and created such devilish intrigues between

mafiosi

and men of the law. Calabria remained Italy’s poorest and most neglected region. The ’ndrangheta could be forgotten because the region it came from simply did not count.

Cinema proved unable to resist the story of the King of Aspromonte, however. Under Fascism, Benito Mussolini blocked any attempt to make a film of Musolino’s life because of the similarity in their surnames. Finally, in 1950, two of Italy’s biggest stars, Amedeo Nazzari and Silvana Mangano, were cast in

Il brigante Musolino

. Filmed on location on Aspromonte, the movie told how Musolino was unjustly imprisoned for murder on the basis of false testimonies, and then escaped to become an outlaw hero. The film did well among the Italian community in the United States.

Giuseppe Musolino died in January 1956 aged seventy-nine. Up and down Italy, the newspapers told his story one more time, and called him ‘the last romantic bandit’.