Dennis Wheatley - Duke de Richleau 07 (90 page)

Read Dennis Wheatley - Duke de Richleau 07 Online

Authors: The Second Seal

On the 11th he gracefully

fulfilled the role of guest of honour at the Marquise de Frontignac’s lunch.

About thirty people were present, the great majority being middle-aged, heavily

bejewelled women. As he was introduced to them, few of their names meant

anything to him, but he realized that they were the wives of wealthy men and

had social ambitions. In every great capital there were many of. their kind

who, for the privilege of lunching with a Marquise and meeting a Duke with an

ancient name and romantic background, would willingly give big sums to charity.

He was pleased that he had come, as he felt certain that the draw of his

presence would enable his

ch

è

re

Madeleine to make a good haul.

After the meal they

adjourned to the Marquise’s

salon.

An elderly tabby-cat man, of the type who always seems to stage manage such

affairs, called for silence. The Marquise produced some notes and studied them

for a moment through her lorgnette. Then she addressed the company:

“My dear friends, I have

a confession to make. I feel I have got you here to-day under false pretences.

Perhaps that was very naughty of me; but I wanted to speak to you about the

charity that means so much to me. Now, please don’t be angry. I know how

generously you are all giving to the new war charities for our poor, brave

wounded. But we should not forget our other obligations. Both in peace and war

more people are killed by disease than by bullets. Alas, we cannot stop the

bullets of our wicked enemy; but we can help to save lives threatened by

disease. Most of you know of the great work in which I am so deeply interested.

It is the checking of that greatest of all scourges—Tuberculosis. I want your

help—your generous help—to stamp this awful plague out once and for all from

our dear France. And I wish to remind you of one thing. I do not appeal to you

now only to help to protect the poor. This terrible disease is so contagious

that every day it menaces your own dear ones. A consumptive nursemaid may

easily give it to your children. No one of us is too rich, too far removed from

the slums, of too high station, for our homes not to be threatened by it.

“Let me give you an

example. Many of you will recall the beautiful young Archduchess, Ilona Theresa

of Austria, who stayed in Paris for a short time this spring, on her way to

England. She was then a lovely, healthy girl, full of the joy of life. In the

summer she contracted tuberculosis. She became subject to a galloping

consumption. Only yesterday I saw the great Swiss specialist, Dr. Bruckner, who

has been attending her. He tells me that now he cannot give her more than three

weeks to live—”

HAPTER

XXVIII

-

ACROSS THE RHINE

Two afternoons later, De

Richleau was standing in the fringe of a pine wood on the west bank of the

Upper Rhine. With the same pair of powerful Zeiss glasses that, eighteen

afternoons earlier, he had used to study the German-Dutch frontier, he now

scrutinized that between Switzerland and Austria. He had felt then that his

life depended on his getting out of the territories controlled by the Central

Empires: he felt now that something worth more than his life depended on

getting into them again.

Madeleine de Frontignac’s

innocent disclosure about Ilona had struck him like a thunderbolt. He had known

for a long time that her illness was more serious than she admitted, and

latterly that it was a matter for considerable anxiety: but he had not thought

for one moment that she was in any danger of death. Yet the Marquise’s report

had not been based on idle gossip. She had received it from Dr. Bruckner.

Her terrible words had

temporarily paralysed De Richleau’s brain. He felt sure that his social

instincts had carried him through the last half hour of the party, and that he

had said the appropriate things to her and her guests before leaving; but he

could remember practically nothing about that. His mind had become obsessed

with the thought that, if Ilona had only a few weeks to live, he must get to

her at the earliest possible moment.

He had had neither

compunction nor difficulty in terminating the work he had been given on the

fateful evening of September the 4th. Returning at once to Melun, he had told

Sir Pellinore the facts. The Baronet had agreed that his commitment was an

entirely voluntary one, and that he was free to go whenever he wished. After an

earnest expression of his sympathy, he added:

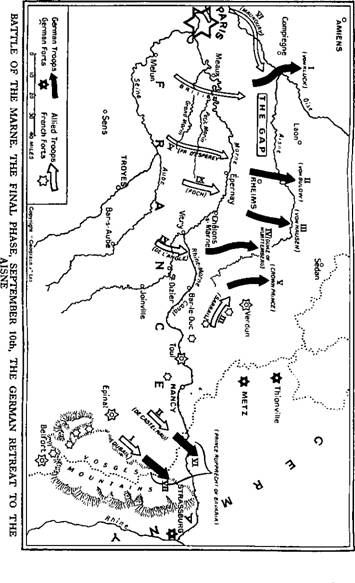

“Battle’s won now,

anyway. Sir John’s movin’ his H.Q. forward to-morrow. So I’m goin’ home myself.

Thunderin’ glad to have had the chance to lend a hand here. Experience I’ll

never forget. But many more urgent things than drawin’ lines on maps with

coloured pencils waitin’ my attention in London.”

Sir Henry Wilson had

proved equally amenable. To him the Duke simply said that he wished to be

relieved of his duties on account of private affairs that needed immediate

attention.

“I’m sorry you’re leaving

us,” the General said. “But you know the position as well as I do. The Huns are

digging in on the Aisne, and the French haven’t another kick left in them; so

there is bound to be a stalemate now for several weeks. It may even be the

sprint! before either side has recovered sufficiently to launch another full

scale offensive. You’ve been a big help to us in the past week, but it is no

longer necessary for us to keep in such constant touch with General Galli

é

ni.

How long do you think it will take you to arrange these affairs of yours?”

“About a month,” De

Richleau had informed him glumly.

“Well, when you’re

through, if you care to come back to us, we’d be glad to have you. I’m afraid I

can’t promise you the rank of Brigadier-General. But hundreds of people are

being given temporary commissions now, and experts of all kinds are being

granted field rank at once to enable them to be used to the best advantage. I

should have no difficulty in getting you made a G.S.O.I., and with your ability

you would. soon be stepped up to full Colonel.”

If anything could have

pleased the Duke, the thought that he could now take up a post in which he

could use his military knowledge would have done so. But for him the future was

filled with nightmare uncertainties. Nevertheless, he thanked Sir Henry with

all the cordiality he could muster, and promised to report for duty as soon as

his affairs were settled.

Next morning, Sir

Pellinore saw the British Ambassador for him and secured him a permit to enter

Switzerland. He bought himself a civilian outfit, packed his uniform into a

suitcase and parked it at the Ritz. After lunch they parted with regret and

affection; Sir Pellinore to return to England, De Richleau to seek a way of

reaching Ilona’s deathbed. so that he might give her the comfort of his

presence when she died.

Early on Saturday, the

13th, he had arrived at St. Gall, near the south-east corner of Lake Constance.

There, he bought a large scale map and hired a car to drive him the fifteen

miles through the Appenzell to the village of Alst

ä

tten.

In the village he had paid off his hired car and lunched; then gone out on his

reconnaissance.

Alst

ä

tten

lay on a slope of the mountain range he had just crossed. To the east of it

spread the low ground of the Rhine valley, which was there some eight miles

wide; then on the Austrian side the ground rose steeply again to the mountains

of the Vorarlberg. About four miles below him lay the village of Kriesseren; a

mile beyond it wound the river, and two miles beyond that another village which

he knew must be Hohenembs. For a few moments he searched the heights above it

intently, knowing that the Imperial villa would be somewhere upon them. On one

spur he could see a little irregular patch which he thought might be it.

Having mastered the

general lie of the land from his vantage point, he returned to Alst

ätten

,

and took a local ’bus down into Kriesseren. There was a little hotel there with

a vine-covered terrace overlooking the river. From it he could now see the

patch with his naked eye and confirmed his belief that it was a large châlet.

At that hour in the

afternoon the terrace was deserted, and having ordered himself a Kirschwasser

he got into conversation with the waitress. She was a daughter of the

proprietor, and lamented that the war had ruined the summer tourist trade of

Switzerland. Few foreigners were coming there now, apart from invalids, and

they were no good to a little hotel lying on low ground near the river.

After a while he pointed

to the châlet, remarking on its lovely situation, and asked if she knew who

owned it.

“The Emperor of Austria,”

she replied. “It is occupied now by an Austrian Princess. I forget her name,

but she is said to be very beautiful. She came there for her health soon after

the war started, but they say she is in a bad way and unlikely to recover.”

He winced, looked quickly

away, and said: “In spite of the war, you still get news then of what goes on

over there across the river?”

“Oh yes,” she nodded. “We

are not at war with Austria, God be thanked; so trade continues. But they are

very careful now who they let in and out, because of spies and deserters.”

After finishing his

drink, the Duke walked down to the bank of the river. The Rhine was not very

broad there, so he knew that he could easily swim it, but, obviously, it would

be preferable if he could get a boat to take him over. As it was not a war

zone, there were no defences, but he felt certain that, even in peace time,

occasional night patrols would be on the look-out for people endeavouring to

enter Austria clandestinely.

Britain was the only

country in Europe which had continued to allow the products of other countrys’

cheap labour to be dumped without limit or tax upon her. All the others

protected their principal industries by duties; so, although travellers had

been permitted to pass freely from one to another, all European frontiers had

customs guards stationed alone; them to prevent illegal imports.

This had resulted in the

creation of a vast international smuggling organization, and the gradual

building up of a complete system of underground communications. De Richleau

knew that on the frontiers of all countries still at peace the smugglers’

operations would have continued to function, and he felt that if he could get

in touch with the local Rhine smugglers they would easily be able to put him

across.

Strolling back to the

village, he began to make a round of the few peasant drinking dens that it

contained. At the first he tried, a sour-faced woman brought him his drink and

regarded him with quick suspicion when he endeavoured to get her to talk about

smuggling; but at the second he was luckier. Two fairly prosperous looking men

were drinking there, and readily accepted his offer that they should join him

in another round. They were not very communicative on the subject of smuggling,

but admitted that it went on in the neighbourhood. After a while he took the

bull by the horns, said that he wanted to get across the river that night and,

under the table, showed them a handful of French gold.

The chances that a police

spy would possess so much foreign money were remote, so the sight of it allayed

their suspicions. They discussed the matter between themselves in

patois

for a few minutes, then told De Richleau that for

twenty

louis d’or

his crossing could be arranged. It was decided that he should dine at the

little hotel and remain there till it closed, then return to the drinking den,

and when the moon was down someone would take him across.

Everything went without a

hitch. The moon did not set till three, but it was a night of drifting cloud

with few stars, and soon after four o’clock he was put ashore at a derelict

landing stage on the Austrian bank.