Destiny Disrupted: A History of the World Through Islamic Eyes (5 page)

Read Destiny Disrupted: A History of the World Through Islamic Eyes Online

Authors: Tamim Ansary

BOOK: Destiny Disrupted: A History of the World Through Islamic Eyes

7.85Mb size Format: txt, pdf, ePub

The Roman Empire, meanwhile, was falling apart. In 293, the emperor Diocletian divided the empire in four parts for administrative purposes: it had grown just too huge and cumbersome to run from a single center. But Diocletian’s reform ended up splitting the empire in two. The wealth was all in the east, it turned out, so the western part of the Roman Empire crumbled. As nomadic German tribes moved into the empire, government services shrank, law and order broke down, and trade decayed. Schools

foundered, western Europeans stopped reading or writing much, and Europe sank into its so-called Dark Ages. Roman cities in places like Germany and France and Britain fell into ruin, and society simplified down to serfs, warriors, and priests. The only institution binding disparate locales together was Christianity, anchored by the bishop of Rome, soon known as the pope.

foundered, western Europeans stopped reading or writing much, and Europe sank into its so-called Dark Ages. Roman cities in places like Germany and France and Britain fell into ruin, and society simplified down to serfs, warriors, and priests. The only institution binding disparate locales together was Christianity, anchored by the bishop of Rome, soon known as the pope.

The eastern portion of the Roman Empire, headquartered in Constantinople, continued to hang on. The locals still called this entity Rome but to later historians it looked like something new, so retrospectively they gave it a new name: the Byzantine Empire.

Orthodox Christianity was centered here. Unlike Western Christianity, this church had no pope-like figure. Each city with a sizable Christian population had its own top bishop, a “metropolitan,” and all the metropolitans were supposedly equal, although the top bishop of Constantinople was more equal than most. Above them all, however, stood the emperor. Western learning, technology, and intellectual activity contracted to Byzantium. Here, writers and artists continued to produce books, paintings, and other works, yet once eastern Rome became the Byzantine Empire it more or less passed out o

f Western history.

f Western history.

Many will dispute this statement—the Byzantine Empire was Christian, after all. Its subjects spoke Greek, and its philosophers . . . well, let us not speak too much about its philosophers. Almost any well-educated Westerner knows of Socrates, Plato, and Aristotle, not to mention Sophocles, Virgil, Tacitus, Pericles, Alexander of Macedon, Julius Caesar, Augustus, and many others; but apart from academics who specialize in Byzantine history, few can name three Byzantine philosophers, or two Byzantine poets, or one Byzantine emperor after Justinian. The Byzantine Empire lasted a

lmost a thousand years, by few can name five events that took place in the empire during all that time.

lmost a thousand years, by few can name five events that took place in the empire during all that time.

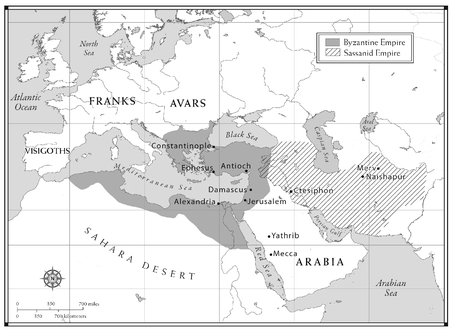

Compared to ancient Rome, the Byzantine Empire didn’t wield much clout, but in its own region it was a superpower, largely because it had no competition and because its walled capital of Constantinople was probably the most impregnable city the world had ever known. By the mid-sixth century, the Byzantines ruled most of Asia Minor and some of what we now call eastern Europe. They butted right up against Sassanid Persia, the region’s other superpower. The Sassanids ruled a swath of land stretch

ing east to the foothills of the Himalayas. Between the two empires lay a strip of disputed territory, the lands along the Mediterranean shore, where the two world histories overlap and where disputes have been endemic. To the sou

th, in the shadow of both big empires, lay the Arabian Peninsula, inhabited by numerous autonomous tribes. Such was the political configuration of the Middle World just before Islam was born.

ing east to the foothills of the Himalayas. Between the two empires lay a strip of disputed territory, the lands along the Mediterranean shore, where the two world histories overlap and where disputes have been endemic. To the sou

th, in the shadow of both big empires, lay the Arabian Peninsula, inhabited by numerous autonomous tribes. Such was the political configuration of the Middle World just before Islam was born.

ON THE EVE OF ISLAM: THE BYZANTINE AND SASSANID EMPIRES

2

The Hijra

Year Zero

622 CE

622 CE

I

N THE LATE sixth century of the Christian age, a number of cities flourished along the Arabian coast as hotbeds of commerce. The Arabians received goods at Red Sea ports and took camel caravans across the desert to Syria and Palestine, transporting spice and cloth and other trade goods. They went north, south, east, and west; so they knew all about the Christian world and its ideas, but also about Zoroaster and his ideas. A number of Jewish tribes lived among the Arabs; they had come here after the Romans had driven them out of Palestine. Both the Arabs and the Jews were Semitic an

d traced their descent to Abraham (and through him to Adam). The Arabs saw themselves as the line descended from Abraham’s son Ishmael and his second wife, Hagar. The stories commonly associated with the Old Testament—Adam and Eve, Cain and Abel, Noah and his ark, Joseph and Egypt, Moses and the pharaoh, and the rest of them—were part of Arab tradition too. Although most of the Arabs were pagan polytheists at this point and the Jews had remained resolutely monotheistic, the two groups were otherwise more or less indistinguishable in terms of culture and lifestyle: the Jews of this area spoke Arabic, and th

eir tribal structure resembled that of the Arabs. Some Arabs were nomadic Bedouins

who lived in the desert, but others were town dwellers. Mohammed, the prophet of Islam, was born and raised in the highly cosmopolitan town of Mecca, near the Red Sea coast.

N THE LATE sixth century of the Christian age, a number of cities flourished along the Arabian coast as hotbeds of commerce. The Arabians received goods at Red Sea ports and took camel caravans across the desert to Syria and Palestine, transporting spice and cloth and other trade goods. They went north, south, east, and west; so they knew all about the Christian world and its ideas, but also about Zoroaster and his ideas. A number of Jewish tribes lived among the Arabs; they had come here after the Romans had driven them out of Palestine. Both the Arabs and the Jews were Semitic an

d traced their descent to Abraham (and through him to Adam). The Arabs saw themselves as the line descended from Abraham’s son Ishmael and his second wife, Hagar. The stories commonly associated with the Old Testament—Adam and Eve, Cain and Abel, Noah and his ark, Joseph and Egypt, Moses and the pharaoh, and the rest of them—were part of Arab tradition too. Although most of the Arabs were pagan polytheists at this point and the Jews had remained resolutely monotheistic, the two groups were otherwise more or less indistinguishable in terms of culture and lifestyle: the Jews of this area spoke Arabic, and th

eir tribal structure resembled that of the Arabs. Some Arabs were nomadic Bedouins

who lived in the desert, but others were town dwellers. Mohammed, the prophet of Islam, was born and raised in the highly cosmopolitan town of Mecca, near the Red Sea coast.

Meccans were wide-ranging merchants and traders, but their biggest, most prestigious business was religion. Mecca had temples to at least a hundred pagan deities with names like Hubal, Manat, Allat, al-Uzza, and Fals. Pilgrims streamed in to visit the sites, perform the rites, and do a little business on the side, so Mecca had a busy tourist industry with inns, taverns, shops, and services catering to pilgrims.

Mohammed was born around the year 570. The exact date is unknown because no one was paying much attention to him at the time. His father was a poor man who died when Mohammed was still in the womb, leaving Mohammed’s mother virtually penniless. Then, when Mohammed was only six, his mother died too. Although Mohammed was a member of the Quraysh, the most powerful tribe in Mecca, he got no status out of it because he belonged to one of the tribe’s poorer clans, the Banu (“clan” or “house of ”) Hashim. One gets the feeling that this boy grew up feeling quite keenly his uncertain status as an orph

an. He was not abandoned, however; his close relatives took him in. He lived with his grandfather until the old man died and then with his uncle Abu Talib, who raised him like a son—yet the fact remained that he was a nobody in his culture, and outside his uncle’s home he probably tasted the disdain and disrespect that was an orphan’s lot. His childhood planted in him a lifelong concern for the plight of widows and orphans.

an. He was not abandoned, however; his close relatives took him in. He lived with his grandfather until the old man died and then with his uncle Abu Talib, who raised him like a son—yet the fact remained that he was a nobody in his culture, and outside his uncle’s home he probably tasted the disdain and disrespect that was an orphan’s lot. His childhood planted in him a lifelong concern for the plight of widows and orphans.

When Mohammed was twenty-five, a wealthy widowed businesswoman named Khadija hired him to manage her caravans and conduct business for her. Arab society was not kind to women as a rule, but Khadija had inherited her husband’s wealth, and the fact that she held on to it suggests what a powerful and charismatic personality she must have had. Mutual respect and affection between Mohammed and Khadija led the two to marriage, a warm partnership that lasted until Khadija’s death twenty-five years later. And even though Arabia was a polygynous society in which having only one wife must have been u

ncommon, Mohammed married no one else as long as Khadija lived.

ncommon, Mohammed married no one else as long as Khadija lived.

As an adult, then, the orphan built quite a successful personal and business life. He acquired a reputation for his diplomatic skills, and quarreling parties often called upon him to act as an arbiter. Still, a

s Mohammed approached the age of forty, he began to suffer what we might now call a midlife crisis. He grew troubled about the meaning of life. Looking around, he saw a society bursting with wealth, and yet amid all the bustling prosperity, he saw widows eking out a bare living on charity and orphans scrambling for enough to eat. How could this be?

s Mohammed approached the age of forty, he began to suffer what we might now call a midlife crisis. He grew troubled about the meaning of life. Looking around, he saw a society bursting with wealth, and yet amid all the bustling prosperity, he saw widows eking out a bare living on charity and orphans scrambling for enough to eat. How could this be?

He developed a habit of retreating periodically to a cave in the mountains to meditate. There, one day, he had a momentous experience, the exact nature of which remains mysterious, since various accounts survive, possibly reflecting various descriptions by Mohammed himself. Tradition has settled on calling the experience a visitation from the angel Gabriel. In one account, Mohammed spoke of “a silken cloth on which was some writing” brought to him while he was asleep.

1

In the main, however, it was apparently an oral and personal interaction, which started when Mohammed, meditating in the utte

r darkness of the cave, sensed an overwhelming and terrifying presence: someone else was in the cave with him. Suddenly he felt himself gripped from behind so hard he could not breathe. Then came a voice, not so much heard as felt throughout his being, commanding him to “recite!”

1

In the main, however, it was apparently an oral and personal interaction, which started when Mohammed, meditating in the utte

r darkness of the cave, sensed an overwhelming and terrifying presence: someone else was in the cave with him. Suddenly he felt himself gripped from behind so hard he could not breathe. Then came a voice, not so much heard as felt throughout his being, commanding him to “recite!”

Mohammed managed to gasp out that he could not recite.

The command came again: “Recite!”

Again Mohammed protested that he could not recite, did not know

what

to recite, but the angel—the voice—the impulse—blazed once more: “Recite!” Thereupon Mohammed felt words of terrible grandeur forming in his heart and the recitation began:

what

to recite, but the angel—the voice—the impulse—blazed once more: “Recite!” Thereupon Mohammed felt words of terrible grandeur forming in his heart and the recitation began:

Recite in the name of your Lord Who created,

Created humans from a drop of blood.

Recite!

And your Lord is most Bountiful.

He who taught humans by the pen,

taught humans that which they knew not.

Created humans from a drop of blood.

Recite!

And your Lord is most Bountiful.

He who taught humans by the pen,

taught humans that which they knew not.

Mohammed came down from the mountain sick with fear, thinking he might have been possessed by a jinn, an evil spirit. Outside, he felt a presence filling the world to every horizon. According to some accounts, he saw a light with something like a human shape within it, whi

ch was only more thunderous and terrifying. At home, he told Khadija what had happened, and she assured him that he was perfectly sane, that his visitor had really been an angel, and that he was being called into service by God. “I believe in you,” she said, thus becoming Mohammed’s first follower, the first Muslim.

ch was only more thunderous and terrifying. At home, he told Khadija what had happened, and she assured him that he was perfectly sane, that his visitor had really been an angel, and that he was being called into service by God. “I believe in you,” she said, thus becoming Mohammed’s first follower, the first Muslim.

At first, Mohammed preached only to his intimate friends and close relatives. For a time, he experienced no further revelations, and it depressed him: he felt like a failure. But then the revelations began to come again. Gradually, he went public with the message, until he was telling people all around Mecca, “There is only one God. Submit to His will, or you will be condemned to hell”—and he specified what submitting to the will of God entailed: giving up debauchery, drunkenness, cruelty, and tyranny; attending to the plight of the weak and the meek; helping the poor; sacrificing for justice

; and serving the greater good.

; and serving the greater good.

Among the many temples in Mecca was a cube-shaped structure with a much-revered cornerstone, a polished black stone that had fallen out of the sky a long time ago—a meteor, perhaps. This temple was called the Ka’ba, and tribal tales said that Abraham himself had built it, with the help of his son Ishmael. Mohammed considered himself a descendant of Abraham and knew all about Abraham’s uncompromising monotheism. Indeed, Mohammed didn’t think he was preaching something new; he believed he was renewing what Abraham (and countless other prophets) had said, so he zeroed in on the Ka’

ba. This, he said, should be Mecca’s only shrine: the temple of Allah.

ba. This, he said, should be Mecca’s only shrine: the temple of Allah.

Al

means “the” in Arabic, and

lah,

an elision of

ilaah,

means “god.”

Allah,

then, simply means “God.” This is a core point in Islam: Mohammed wasn’t talking about “this god” versus “that god.” He wasn’t saying, “Believe in a god called Lah because He is the biggest, strongest god,” nor even that Lah was the “only true god” and all the other ones were fake. One could entertain a notion like that and still think of God as some particular being with supernatural powers, maybe a creature who looked like Zeus, enjoyed immortality, could lift a hundred camels with one hand, and was th

e only one of its kind. That would still constitute a belief in one god. Mohammed was proposing something different and bigger. He was preaching that there is one God too all-encompassing and universal to be associated with any particular image, any particular attributes,

any finite notion, any limit. There is only God and all the rest is God’s creation: this was the message he was delivering to anyone who would listen.

means “the” in Arabic, and

lah,

an elision of

ilaah,

means “god.”

Allah,

then, simply means “God.” This is a core point in Islam: Mohammed wasn’t talking about “this god” versus “that god.” He wasn’t saying, “Believe in a god called Lah because He is the biggest, strongest god,” nor even that Lah was the “only true god” and all the other ones were fake. One could entertain a notion like that and still think of God as some particular being with supernatural powers, maybe a creature who looked like Zeus, enjoyed immortality, could lift a hundred camels with one hand, and was th

e only one of its kind. That would still constitute a belief in one god. Mohammed was proposing something different and bigger. He was preaching that there is one God too all-encompassing and universal to be associated with any particular image, any particular attributes,

any finite notion, any limit. There is only God and all the rest is God’s creation: this was the message he was delivering to anyone who would listen.

Mecca’s business leaders came to feel threatened by Mohammed because they were making good money from religious tourism; if this only-one-god idea took hold, they feared, the devotees of all the other gods would stop coming to Mecca and they’d be ruined. (Today, ironically, over a million people come to Mecca each year to perform the rites of pilgrimage at the Ka’ba, making this the biggest annual gathering on earth!)

Other books

Witch House by Dana Donovan

White Narcissus by Raymond Knister

The Wordy Shipmates by Sarah Vowell

Elm Creek Quilts [06] The Master Quilter by Jennifer Chiaverini

Dog by Bruce McAllister

Extraordinary by David Gilmour

Breaking Point by Kit Power

Saddlebags by Bonnie Bryant

Knowing the Ropes by Teresa Noelle Roberts

The Hero's Walk by Anita Rau Badami