Embers of War (40 page)

Authors: Fredrik Logevall

Tags: #History, #Military, #Vietnam War, #Political Science, #General, #Asia, #Southeast Asia

Revers in his report catalogued many of these problems and drew sobering conclusions. No military solution favoring France was possible, he argued, not in the long run. All actions must proceed from this basis, and ultimately Paris leaders would need to seek a “peace of the brave” with Ho Chi Minh’s Democratic Republic of Vietnam. Bao Dai was a poor leader whose government had minimal support, and France did not have enough manpower in Indochina to impose her will on the population. Since the Viet Minh were bound, sooner or later, to gain significant assistance from the Chinese Communists, France could not realistically hope to hold the whole of Tonkin (at least not without the introduction of American ground forces); instead, she should withdraw from all of Tonkin except a rough quadrilateral around the Red River Delta anchored on Haiphong, Hoa Binh, Viet Tri, Thai Nguyen, and Mong Cai. The fortresses on the Chinese frontier along Route Coloniale 4, already suffering from the relentless attacks on the convoys, would become indefensible if the PLA reached the border and decided to aid the Viet Minh. They were, moreover, strategically unimportant and were tying down troops badly needed in the Red River Delta.

39

The Revers report was top secret and was made for the private information of senior French policy makers. It thus caused an uproar when excerpts from it were broadcast on Viet Minh radio and when, following a fight between a French soldier and a Vietnamese student on a Paris bus, a copy of the report was discovered in the latter’s briefcase. The student, Do Dai Phuoc, led French counterespionage agents to another Vietnamese student’s apartment, where they found seventy-two additional copies. Subsequent investigation revealed that the document had circulated widely within the French capital’s large Vietnamese community. A major political scandal—“The Generals’ Affair”—erupted, preoccupying the chattering classes for months and delaying a final decision on Revers’s call for an evacuation of the northern forts.

40

The months went by. In late 1949, Giap stepped up pressure on the convoys along the RC4, and the consolidation of PLA control in South China increased his determination to subject the French installations to a major assault. He grasped what the new French commander in chief, Marcel Carpentier—a wunderkind who had gone from major in 1940 to lieutenant general in 1946, but who knew little about Indochina—also grasped: that these posts were forlorn islands in a Viet Minh sea.

CHAPTER 10

ATTACK ON THE RC4

A

T 6:45

IN THE MORNING OF MAY 25, 1950,

A VIOLENT FUSILLADE

suddenly rained down on the small French garrison (eight hundred men, mostly Moroccan) at Dong Khe, a post situated between Cao Bang and That Khe along the RC4. The post was a bastion in the French military system where convoys could stop to rest in the shelter of the French flag. Giap’s aim: to take and hold Dong Khe, thereby isolating Cao Bang from its links with That Khe. In the days prior, four Viet Minh infantry battalions succeeded in hoisting five 75mm cannons onto the heights surrounding the town without being detected by the garrison, and then proceeded to unleash barrage after barrage on the post. It was a preview of the technique they would use at Dien Bien Phu. For forty-eight hours the shelling continued, whereupon the Viet Minh overran Dong Khe in a human-wave assault.

The French responded quickly, dispatching thirty-four aircraft to drop a battalion of paratroops upon the town. They caught the Viet Minh units completely off guard and after intense fighting forced them to flee for the jungle. Giap had reinforcements he could have called in, but the monsoon was fast approaching, and he chose to call it a day. The French congratulated themselves on their quick deployment of the paratroops rather than face the deeper truth of their extreme vulnerability in the Viet Bac. They chose not to take this last great chance to evacuate the frontier posts while time remained.

1

Giap, having seen what his forces could do in a major engagement, believed the time had come to shift to the strategic offensive. With China as a secure rear base, a sanctuary where his troops could be trained, reorganized, and equipped for more conventional operations, he could prepare to strike the first hammer blow against the French Union. By the late spring, the Viet Minh had grown to a force of about a quarter of a million troops, organized into three components: a regular army (

chu luc

), regional units, and guerrilla-militia forces. The regular forces, with an estimated strength of 120,000, Giap organized into six divisions, on European lines—the 304th, 308th, 312th, 316th, 320th, and 325th; five were rooted in Tonkin, and the sixth (the 325th) was based in central Vietnam. Each had three infantry regiments, an artillery battalion, and an antiaircraft battalion, as well as staff and support elements. The task of these regular forces was to conduct a war of maneuver, aimed at drawing French units into combat in locales and under conditions in which French advantages in firepower and air support would be neutralized. The isolated French garrison in an outlying area was thus always a tempting target, and if the attack could occur during the

crachin

, or misty season in Tonkin, when the low cloud cover inhibited French aerial bombardment and resupply, so much the better.

2

To keep these new formations fighting in the field required complex logistical planning. For example, senior Viet Minh planners determined that maintaining an infantry division in action away from its base required the use of roughly fifty thousand local peasants as porters, each carrying about forty-five pounds in supplies. These numbers could be reduced when bicycles were available—when pushed along roads and tracks by the rider, these specially outfitted vehicles could carry up to two hundred pounds during the dry season—but even then the figure was huge. The porter had to carry his own rations with him, which usually took the form of rice in a cloth bandolier. As a general rule, a porter was not to be away from home for more than two weeks, meaning that he would spend “seven carrying days” with the army unit and then could commence the return journey to his village. Fresh porters would be conscripted as the division continued its journey.

3

The regional and guerrilla-militia forces had vital tasks of their own, mostly related to defensive and security matters but also including small-scale guerrilla operations against static enemy positions. Giap’s early writings stress the importance of these roles. Each province and district had responsibility for raising and equipping its own units of regional troops, who on occasion served as a general reserve for the regular army. At the province level, battalions sometimes comprised several rifle companies and a support company equipped with light machine guns and mortars. Ammunition was often in short supply, but these battalions could take on French units effectively for brief periods of time. Often they also had the task of training the guerrilla-militia forces, who tended to be unarmed or lightly armed and were usually part-timers. Their chief duties included intelligence gathering, transport, and sabotage. A better-armed element of the guerrilla-militia forces, so-called elite irregulars, was equipped with grenades, rifles, and mines, and sometimes even a few automatic weapons. It frequently joined with the regional forces in local operations.

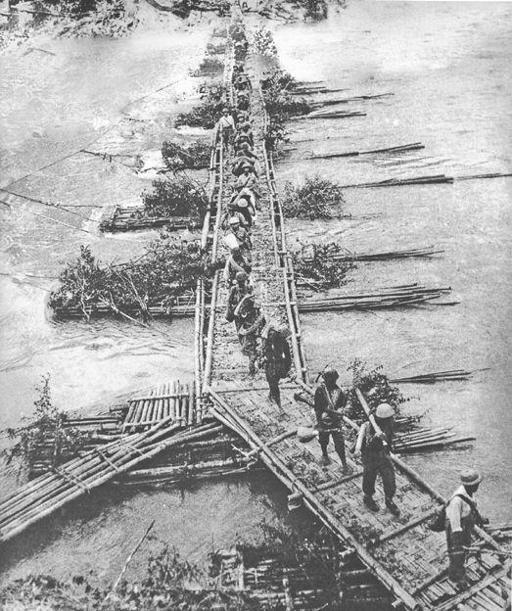

VIET MINH SOLDIERS CROSS A BAMBOO PONTOON BRIDGE IN BAC KAN PROVINCE IN NORTHERN VIETNAM, IN 1950. THIS CONSTRUCTION TECHNIQUE WOULD BE USED FREQUENTLY IN THE WAR AND AGAIN LATER IN THE STRUGGLE AGAINST THE UNITED STATES.

(photo credit 10.1)

Women took on key roles in the war effort. Though barred from enlisting in the regular army, they served by the thousands in the DRV bureaucracy—though almost never in senior positions—and as nurses and doctors. Many also carried out dangerous undercover sabotage, espionage, and assassination missions in the urban areas of Vietnam, or signed up for duty in the guerrilla-militia forces. At one point in Hung Yen province, for example, 6,700 women served in these forces, taking part in 680 guerrilla operations. A considerable number of them paid with their lives or were seriously wounded.

Giap spent the rainy season preparing for a large-scale autumn offensive. There was in effect a truce in the fighting from July to September, as the war came to a stop in the wet. The rain fell almost continuously, and the rivers overflowed. The spongy, saturated jungles were virtually impassable by French troops—and, for that matter, by Viet Minh units—and the going was not much easier in the watery surfaces of the deltas. Recalled one French observer: “The soldiers were overwhelmed and blinded by the forces of nature, by the soaking vegetation, the mountains that vanished in the clouds, the rivers swirling with turbid, dangerously rapid water, by the mud, the heat, by everything. It was a formless, green-gray world, devoid of outline, inimical, a world in which every movement, even eating was an effort.”

4

Resourceful commanders take advantage of such intermissions. Giap and his subordinates engaged in meticulous preparations during the summer months, even going so far as to construct elaborate models of the French posts of That Khe, Dong Khe, and Cao Bang, which their troops then practiced taking, day after day after day. They sabotaged roads and bridges, hoping to slow the advance of French motorized forces. They also used propaganda to wage a war of nerves against the French and the Bao Dai government, playing up the theme of a forthcoming offensive.

Most critical of all, Giap received considerable assistance from the Chinese, as pledged by Mao Zedong to Ho Chi Minh in Moscow and Beijing earlier in the year. On June 18, Liu Shaoqi, vice chairman of the Chinese Communist Party, instructed Chen Geng, commander of the PLA’s Twentieth Army Corps and a longtime acquaintance of Ho Chi Minh, to “work out a generally practical plan based on Vietnam’s conditions (including military establishments, politics, economy, topography, and transportation) and on the limits of our assistance (including, in particular, our shipping supplies).” Upon receiving this plan, Beijing could “implement various aid programs, including making a priority list of materials to be shipped, training cadres, and rectifying troops, expanding recruits, organizing logistical work, and conducting battles.”

5

In short order, Chinese advisers were assigned to numerous Viet Minh units at battalion level and above, and the PRC also provided a large amount of weaponry and other matériel—by one authoritative account more than 14,000 guns, 1,700 machine guns, about 150 pieces of varying kinds of cannons, 2,800 tons of grain, and large amounts of ammunition, uniforms, medicine, and communication equipment. Some 200 heavy Molotova trucks stocked with supplies ran continuously from Canton and across South China, crossing into Vietnam in the gaps in the French defense line northeast of Cao Bang, the western anchor on the RC4. If the amounts in these truck beds still did not come close to matching what Washington gave to the French Union—by early 1951, the French would receive some 7,200 tons of military equipment per month on average—it nevertheless had a highly significant impact. Meanwhile, Viet Minh forces were sent to China’s Yunnan province for training by PLA officers, including in the use of explosives. By early September, they were back in Vietnam, gathered on the lines of penetration, using the jungle to keep themselves hidden.

6

The result was a Viet Minh main battle force in Tonkin whose firepower was roughly equal to that of the French Expeditionary Corps and in some respects superior. In certain heavy weapons, for example, such as bazookas and mortars, a Viet Minh battalion could now outgun its French counterpart. The French retained total superiority in naval vessels, aircraft, armored vehicles, and—with some exceptions—artillery, but overall Giap, by the early autumn of 1950, possessed a fighting force that could accomplish what it had never been able to do before: Go toe-to-toe with the adversary.

7