Examination Medicine: A Guide to Physician Training (72 page)

Read Examination Medicine: A Guide to Physician Training Online

Authors: Nicholas J. Talley,Simon O’connor

Tags: #Medical, #Internal Medicine, #Diagnosis

Remember that you are, in fact, demonstrating the signs (particularly in the case of a neurological short case) to the examiners. It is important to perform each manoeuvre accurately and deliberately. Be seen to be smooth and confident, as if you have done the examination a thousand times before. Also try to be confident of each sign before moving on to another area (e.g. on finding an abdominal mass, concentrate on excluding the various possibilities and coming to a firm conclusion), and do not worry too much about the time it takes. Practice will facilitate formation of conclusions accurately and quickly.

Very occasionally, the examiners will pull a candidate away in the middle of an examination. This is why it is important to synthesise the data as you go. Do not get flustered by this – it usually means that enough of the examination has been completed for you to have discovered the important signs. Examiners no longer require the interpretation of a particular sign in isolation (e.g. the collapsing carotid pulse in aortic regurgitation or the double apex beat in hypertrophic cardiomyopathy).

Usually there is no interruption until the examination is almost finished. We suggest that candidates keep on examining until told to stop, and then list all the other things they would like to have done and why (e.g. urine analysis, rectal examination).

Before presenting the findings, listen closely to the examiners’ instructions. Candidates will often be asked: ‘What did you find?’ at which point they are expected to describe the relevant signs first and then comment on possible causes. Sometimes candidates will be asked: ‘What is your diagnosis?’, at which point they are expected to give a diagnosis or differential diagnosis first and then list the signs supporting the contention.

HINT

Formulate your diagnosis and differential diagnosis based on the individual in front of you.

Using a formulaic presentation of your findings might give you more time to think, but can be intensely irritating for the examiner if this is the fourth time they have heard ‘Mr Smith is an elderly man lying comfortably in bed’. And especially if the patient is no older than the examiners and is obviously breathless and not comfortable.

One useful method of presentation is to first repeat the examiners’ introduction briefly, then give the relevant findings, followed by the provisional diagnosis. For example: ‘I was asked to examine Mr Jones, a 60-year-old man who has had problems with dyspnoea. On examination of his cardiovascular system, I found …’ When describing the signs it is probably easiest to present them in the order they were looked for (e.g. for the cardiovascular system – pulse rate, then blood pressure, then jugular venous pressure). It is important to state all the positive signs and the important negative ones. Be definite about each sign mentioned or do not mention the sign at all. There is no place for expressions such as ‘slightly asymmetrical’ or ‘minor’.

HINT

In neurological examinations, don’t rush to undertake sensory testing which is often frustrating and less reliable. Leave the sensory examination to the end if at all possible.

Alternatively, you may talk as you go. This is not always acceptable to the examiners, and we recommend such an approach only in special cases in adult medicine, because the processing of information is usually more difficult for candidates (see Ch 16).

Confidence is critical to success in the short cases. Do not lose confidence if you make a minor error, just continue – the examiners may not even have noticed.

A short differential diagnosis is usually expected, even if the diagnosis is obvious. For example, a patient with fasciculation, plus upper and lower motor neurone signs in the legs and no sensory loss almost certainly has motor neurone disease, but a non-metastatic manifestation of carcinoma must be considered. Always mention common diseases before rare ones and always consider the patient’s age and sex. Never reel off any old list; the differential diagnosis must be tailored to the particular patient. Sometimes patients will have signs of two different problems. This should not be ignored. For example, a patient with proximal muscle weakness as a result of polymyositis may have unrelated Dupuytren’s contractures.

After presentation of the signs, a few minutes or more are set aside for discussion. The examiners are not encouraged to take the candidate back for a second look at a sign, as this can be extremely unsettling for the candidate and perhaps not fair. However, this does happen occasionally and it is best to think of it as a genuine second chance.

HINT

A redirect represents a genuine second chance – grab hold of the opportunity. There are no tricks in the examination.

From the examiners’ point of view, the candidate who is completely wrong presents a problem. This can occur because he or she has not read the stem properly; for example, when a request to examine the lower cranial nerves leads a candidate to begin to test visual acuity. Sometimes the examination depends on a spot diagnosis. For example, for an obvious acromegalic patient the stem might be: ‘This man has noticed some changes in his hands. Have a look at his face, examine the hands and go on from there.’ The risk here is that the acromegaly is not recognised and the candidate decides the diagnosis is, say, rheumatoid arthritis. The examination and discussion will then have nothing to do with what the examiners had expected and prepared for.

If the candidate’s mistake is recognised early on, the examiners may attempt to redirect the examination. This can be surprisingly difficult. Some candidates persist in continuing the way they began, despite strong hints or even direction from the examiners. This is presumably because they think an attempt is being made to trick them. This never happens.

HINT

If your diagnosis is completely incorrect, a good discussion won’t usually help you.

Sometimes the examination seems to be going well and then the candidate comes out with a completely wrong diagnosis. This makes the examiners’ prepared discussion unuseable. In this case the examiner will likely attempt to continue the discussion along

the lines the candidate has begun. For example, the candidate appears to have examined a patient with small muscle wasting of the hands satisfactorily, but then, against all the evidence, decides the problem is rheumatoid arthritis. The examiners may ask what was found that led to the diagnosis and were there any alternative possibilities, but if no alternatives can be extracted from the candidate they will allow a discussion of rheumatoid arthritis.

This problem usually occurs when a candidate has decided on a diagnosis before looking at the patient. Deciding that the stem was, ‘“examine the hands”, therefore this must be rheumatoid’, must be avoided.

If a candidate has done well in a case and there are a few minutes left for extra questions, the score can only improve. Relevant X-rays or an ECG may be shown to the candidate. Some diagnostic and therapeutic aspects may be discussed in the short case.

HINT

If you have done well, in the last few minutes of discussion your score can only go up, not down. So don’t worry if the depth becomes overwhelming – press on talking about the issues in a mature, sensible fashion!

One examiner will introduce the patient and repeat the stem. This is likely to be the lead examiner. In many cases that examiner will conduct the discussion. There may or may not be an opportunity for the other examiner to ask some questions at the end. This may be a sign that the first one has run out of questions. This doesn’t really tell you whether things are going very well or very badly.

The College has moved away from the traditional ‘spot’ short case (e.g. acromegaly) and now concentrates more on ‘realistic’ cases (e.g. heart murmurs, abdominal masses). However, all types still crop up and candidates must try to prepare for most possibilities. It is also true that the more straightforward the case, the higher the standard of examination that will be expected, and vice versa. Trick cases are deliberately avoided.

The value of some traditional clinical signs is now being questioned as

evidence-based

approaches to clinical examination help establish the validity and utility of signs. There is much work still to be done in this area, but an understanding of the value of signs is increasingly important. A tactful approach may be needed with the examiners to prevent any resentment at the candidate’s failing to look for a traditional sign that is a particular favourite of theirs.

Six golden rules for the short cases

1.

Do

everything

properly when you examine the patient –

never

take short cuts.

2.

Think

and

synthesise

as you examine the patient – be alert.

3.

Never

make up signs and

never

ignore signs because they don’t fit neatly together.

4.

Always

be sure of your facts

when presenting – it’s better to say that you don’t know than to guess.

5.

Always show consideration for the patient and

never

cause the patient pain.

6.

Wash your hands before and after the case.

CHAPTER 16

Common short cases

The trouble with doctors is not that they don’t know enough, but that they don’t see enough.

Corrigan (1802–80)

In the short cases, candidates may be asked to examine a system or a particular part of the patient. Now that 15 minutes is available for each case, ‘spot’ diagnoses alone are not likely to be asked for by the examiners. The following pages outline a system for examining major short-case possibilities. Use this information to help develop your own system. Many useful lists are also included in this section.

We have also provided examples of typical X-rays and scans related to particular short-case examinations. At the end of each short-case discussion the examiners will often ask: ‘What investigations might be helpful in this case?’, and in many cases X-rays, CT scans or MRI scans will be indicated and available for you to look at and comment on.

In all cases, before beginning a specific examination you should stand back for a moment and carefully observe the patient. It is still important to look for an associated ‘spot’ diagnosis, such as peripheral neuropathy in a myxoedematous patient or aortic regurgitation in a patient with Marfan’s syndrome.

The patient will normally be positioned and undressed ready for you to examine. However, if either positioning or undressing is unsatisfactory, correct it. Ask the proctor attendant to help. All hospitals have different bed mechanisms and trying to work out how to adjust the bed when you are anxious is not worth it.

The cardiovascular system

The cardiovascular examination

‘This 50-year-old man presents with dyspnoea on exertion and orthopnoea. Please examine his cardiovascular system.’

HINT

Many candidates worry about where they should start the examination – with the hands or at the praecordium. It rarely matters, but if the instruction is to examine the chest you should do that first. Otherwise, you can start with the hands, but this must be done quickly and efficiently. Some candidates take so long on the periphery that they scarcely have time to examine the praecordium.

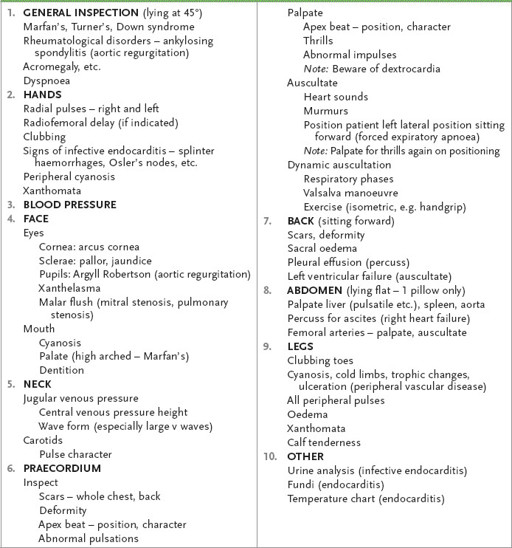

METHOD (SEE

TABLE 16.1

)

Table 16.1

Cardiovascular system examination

1.

Make sure the patient is positioned at 45° and that the patient’s chest and neck are fully exposed. For a woman, the requirements of modesty dictate that you cover her breasts with a towel or loose garment.

2.

While standing back, inspect for the appearance of Marfan’s, Turner’s or Down syndrome. Also look for dyspnoea and cyanosis. It is also worth looking from a distance at the neck. Big V waves are sometimes more obvious from a distance.

HINT

Struggling unsuccessfully with an unfamiliar blood pressure cuff looks very bad – especially when the incorrectly placed cuff crackles and then bursts as you inflate it. Practise taking the blood pressure quickly with different sphygmomanometers.