Examination Medicine: A Guide to Physician Training (96 page)

Read Examination Medicine: A Guide to Physician Training Online

Authors: Nicholas J. Talley,Simon O’connor

Tags: #Medical, #Internal Medicine, #Diagnosis

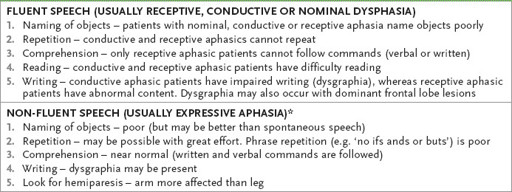

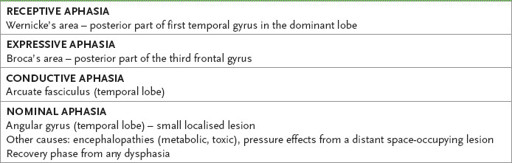

Table 16.52

Examination of dysphasia

*

As the patient is aware of his deficit, he is often frustrated and depressed.

4.

Next, assess the parietal lobes. Begin with the dominant parietal lobe, as Gerstmann’s syndrome is common in examinations.

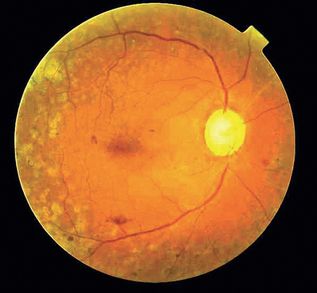

FIGURE 16.52

Diabetic retinopathy. N Efron,

Contact lens practice

, 2nd edn. Fig 35.1. Elsevier, 2010, with permission.

HINT

Dominant parietal lobe evaluation: using the mnemonic AALF, examine for:

Acalculia (test mental arithmetic)

Agraphia (test for an inability to write)

Left–right disorientation (e.g. by asking the patient to put his right palm on his left ear, then vice versa)

Finger agnosia (inability to name individual fingers), which is caused by a left angular gyrus lesion in right-handed and about half of left-handed patients

5. Test general parietal functions (involving either lobe). Examine for sensory and visual inattention. Also test for agraphaesthesia (inability to appreciate numbers drawn on the palm) and astereognosis (inability to name objects placed in the hand). Assess constructional apraxia by asking the patient to draw a clock face and fill in the numbers.

6. The major specific non-dominant parietal dysfunction is dressing apraxia. This can be tested by turning the patient’s pyjama top inside out and asking him to put it on correctly.

7. Assess memory, both short and long term. This is a medial temporal lobe function. Ask the patient to remember the name of three flowers (e.g. Rose, Orchid and Tulip – mnemonic ROT for those candidates with a poor memory) and repeat them immediately. Then assess long-term memory, such as by asking when World War II finished. Ask the names of the flowers again at the end of your higher centres’ examination.

8. Test frontal lobe problems, first by assessing the primitive reflexes (see

Figs 16.92

and

16.93

) normally not present in adults. The grasp reflex, pout reflex and palmar–mental reflex are usually all that need be tested. Then ask for interpretation of a common proverb, such as ‘A rolling stone gathers no moss’. Test for anosmia (cranial nerve I) and gait apraxia (a frontal gait abnormality is marked by gross unsteadiness in walking – the feet typically behave as if glued to the floor, resulting in a hesitant shuffling gait with freezing).

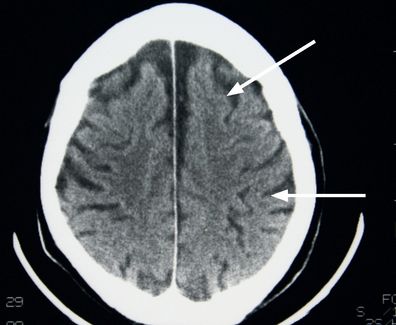

FIGURE 16.92

CT of the brain of a patient with early dementia, showing generalised cerebral atrophy. There is obviously more CSF present than normal (arrows). Figure reproduced courtesy of The Canberra Hospital.

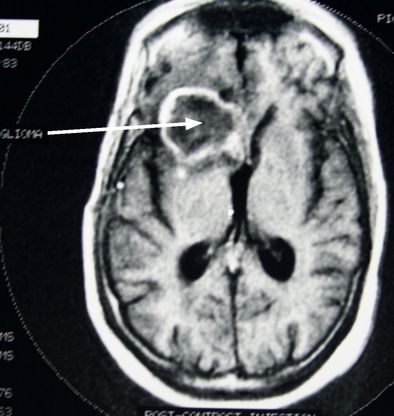

FIGURE 16.93

A frontal glioma found on MRI scan in a patient with frontal lobe signs (arrow). Figure reproduced courtesy of The Canberra Hospital.

9. If there is evidence of a frontal lobe lesion, look at the fundi to exclude the rare Foster Kennedy syndrome (optic atrophy on the side of the lesion and papilloedema in the opposite fundus).

10. Any abnormality of the parietal, temporal or occipital lobes may cause a characteristic visual field loss. This should be tested, if appropriate, at the conclusion of your examination. Other important signs to look for are carotid bruits, hypertension and relevant focal neurological signs.

11. MRI and CT scans may show cerebral atrophy consistent with dementia or sometimes a space-occupying lesion.

Speech

‘Please assess this man’s speech.’

Method

Immediately ask the patient to state his name, age and present location. Then ask him to say ‘British Constitution’. By now you should have decided whether the problem is dysphasia, dysarthria or dysphonia.

DYSPHASIA

1.

If the speech is fluent but conveys information imperfectly, often with paraphasic errors (e.g. ‘treen’ for train – substitution of a word of similar sound), the main possibilities are nominal and receptive dysphasia. Test for these by asking the patient to name objects, to repeat a statement after you and then follow commands. Then ask him to read and write if the above are abnormal (see

Table 16.52

).

2.

If the speech is slow and non-fluent (hesitant), exactly the same procedure is followed, but an expressive dysphasia is likely. At the end ask to assess for a hemiparesis (see

Table 16.52

).

3.

Remember, large lesions may cause global aphasia, with inability to comprehend or speak, plus hemiparesis (see

Table 16.53

).

Table 16.53

The sites of lesions in aphasia

DYSARTHRIA

1.

This is a disorder of articulation with no disorder of the content of speech. Consider cerebellar disease and lower cranial nerve lesions particularly. Cerebellar speech is slurred or ‘scanning’ (i.e. irregular and staccato). Pseudobulbar palsy causes slow, hesitant, hollow-sounding speech with a harsh, strained voice, while bulbar palsy causes nasal speech with imprecise articulation.

2.

Ask the patient to say ‘British Constitution’, ‘West Register Street’, ‘Me Me Me’ and ‘Lah Lah Lah’.

3.

If the speech is cerebellar, go on to this system (p. 457).

4.

If palsy of a lower cranial nerve is likely, examine the lower cranial nerves carefully.

5.

Do not forget to elicit the jaw jerk. Look in the mouth too for ulceration or other local lesions.

6.

Less common causes of dysarthria include extrapyramidal disease and myopathies (p. 451).

DYSPHONIA

This is huskiness of the voice from a laryngeal disorder, recurrent laryngeal nerve palsy or focal dystonia. Assess the quality of the cough too.

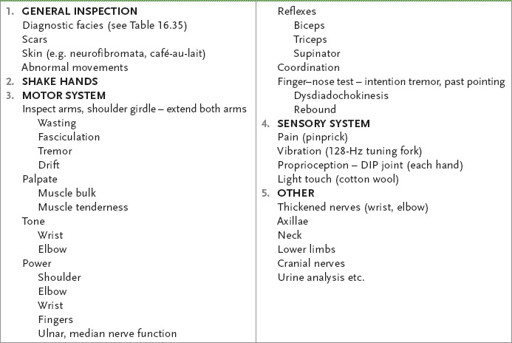

Upper limbs

‘This man has noticed weakness in his arms. Please examine him.’

Method (see

Table 16.54

)

Table 16.54

Upper limb neurological examination

1.

Look at the whole patient briefly. Note particularly evidence of a myopathic face, Parkinsonian features or stroke.

2.

Shake the patient’s hand firmly and introduce yourself. If he cannot let go, you have made the diagnosis: myotonia (usually caused by dystrophia myotonica). Ask him to sit over the side of the bed facing you.

MOTOR SYSTEM

Examine the motor system systematically every time.

1.

Inspect first for wasting (both proximally and distally) and fasciculations. Do not forget to include the shoulder girdle in your inspection (p. 436).

2.

Ask the patient to hold both his hands out with the arms extended and close his eyes. Look for drifting of one or both arms. There are only three causes for this drift:

a.

upper motor neurone weakness (usually downwards owing to muscle weakness)

b.

cerebellar lesion (usually upwards owing to hypotonia)

c.

posterior column loss (any direction owing to joint position sense loss).

3.

Also note any tremor and pseudoathetosis as a result of proprioceptive loss.

4.

Feel the muscle bulk next, both proximally and distally, and note any muscle tenderness. In the presence of wasting and weakness, fasciculation indicates lower motor neurone degeneration.