Read Explorers of the Nile: The Triumph and Tragedy of a Great Victorian Adventure Online

Authors: Tim Jeal

Tags: #Non-Fiction, #Travel, #Adventure, #History

Explorers of the Nile: The Triumph and Tragedy of a Great Victorian Adventure (10 page)

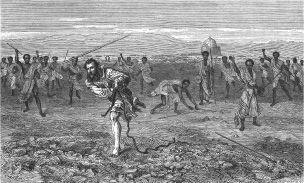

Speke’s escape from his captors (frontispiece of Speke’s

What Led to the Discovery of the Source of the Nile

).

Speke’s resentment against Burton for implying that he had been retreating at the height of the attack was not his only complaint against his leader. As expedition leader, Burton had taken possession of his junior officer’s diary and, although Speke could hardly object to a copy being sent to the Bombay authorities, he knew that Burton was an author and suspected that he might make personal use of the copy he had retained. He was also shocked when Burton told him that he was bound by his instructions to send to the Calcutta Museum of Natural History all the animals’ heads and other specimens he had collected.

Speke had hoped at least to send duplicates to his own private museum in his father’s house.

34

Yet it could be said in Burton’s favour that he was at least trying his hardest to get back the £510, which Speke had lost, along with a further thousand lost by other expedition members in the destruction of their camp. Speke was always aware of the need to keep on good terms with his leader in order to be invited to accompany him on his next expedition. So he did not reproach Burton for failing to negotiate a penny of compensation from the East India Company.

While at Kurrum, Speke had heard of the existence of a vast inland lake, which ‘the Somali described as equal in extent to the Gulf of Aden’.

35

This information made him all the keener to keep in with Burton – although there could be no denying that their Somaliland expedition had been such ‘a signal failure from inexperience’ that it had probably damaged their reputations too much to make funding a new journey a practical proposition.

36

Yet Burton had at least reached Harar, so

his

credibility had not been entirely ruined. Yet even supposing Burton managed to gain support in the right quarters, Speke doubted whether his former leader would want to return to Africa with a man who had written no books, knew no Arabic, and had failed to reach the objective he had been set.

FOUR

About a Rotten Person

When Richard Burton arrived in England on sick leave in June 1855, the two volumes of his

Pilgrimage to El-Medinah and Meccah

were in the shops and had just received the kind of press that normally makes an author well known for life. But circumstances were far from normal, with public attention riveted by the Crimean War and the cholera, starvation, dysentery and official incompetence that were together killing more British soldiers than the enemy. Britain and France were at war with Russia in defence of threatened Turkey and their own interests in the eastern Mediterranean. Though Burton had returned from Africa marked for life by a livid facial scar, he wanted to go and fight. Not that patriotism fully explained his ardour.

He had just been severely censured by Aden’s new British ruler, Brigadier William Coghlan, for his ‘want of caution and vigilance’ as leader of the Somali Expedition.

1

Fearing that Coghlan’s report could blight his chances of returning to Africa, he decided that a stint in the Crimea might persuade the Bombay government to view him more favourably. The best he could manage was a staff appointment with Beatson’s Horse, a lawless brigade of Turkish irregulars. However, within three months – during which Burton saw no action – he and the brigade’s other British officers failed to stop their ill-disciplined Turks, Syrians and Albanians clashing with French troops, their allies. General Beatson was forced to resign, and Burton, as his chief staff officer, had no choice but to follow him home.

2

Yet at this apparently disastrous moment, luck came to his rescue in a most unexpected way.

Dr James Erhardt, a missionary colleague of Dr Krapf and Johann Rebmann, sent a map of a gigantic slug-shaped central African lake to the secretary of the Church Missionary

Society, who forwarded it to the Royal Geographical Society, where it was discussed at meetings in late November and early December 1855 – the very time when Burton had just come home. Although the geographers’ general opinion of this map – which was based on the testimony of Arab-Swahili slave traders – was that it incorrectly conflated a southern lake with one, or possibly two lakes further to the north, its implications for the search for the Nile’s source were electrifying.

3

Because Burton knew the RGS’s secretary, Dr Norton Shaw, he had been kept abreast of the Society’s evolving plans, and so was in pole position to apply for the leadership of a new East African expedition. Indeed, Burton’s letter of application reached the Society two days before their Expeditions’ Committee resolved on 12 April 1856 to send an exploring party ‘to ascertain . . . the limits of the Inland Sea or Lake . . . [and, if possible, achieve] the determination of the head sources of the White Nile’.

4

By the time Burton wrote again, a week after this meeting, it was evident that he had already been informed

sub rosa

that the RGS meant to back him. At any rate, he felt confident enough to discuss with them a pivotal matter – which was whether to go alone, or accompanied. He plumped for the latter option, because ‘it would scarcely be wise to stake success upon a single life … I should therefore propose as my companion, Lt. Speke of the B.A. [Bengal Army]’.

5

If Speke had been in a position to hear that Burton had made him his first choice at this historic moment, he would have been amazed. But he was out of contact in the Crimea, and currently stationed at Kertch as second in command of the Turkish contingent of the 16th Regiment of Infantry. But, as he told a friend at this time, he had no interest in the war and ‘was dying to go back and try again [at the Nile]’, but doubted whether he would ever be given the chance.

6

So when he eventually received the good news from Norton Shaw, he was planning a hunting expedition in the Caucasus Mountains.

7

Although still smarting from the accusation of cowardice and the theft of his specimens, Speke did not hesitate to accept

Burton’s invitation. His former commander – as he was aware -’knew nothing of astronomical surveying, of physical geography, or of collecting specimens of natural history’, so he was confident that his own practical skills would be invaluable.

8

It is not easy to judge what the two men thought of one another before they began their second journey. This is because, after it, every word they wrote (and they wrote a good many) would be coloured by their great falling out. Burton’s own version of why he invited Speke to accompany him is highly suspect:

The history of our companionship is simply this: – As he had suffered with me in purse and person at Berbera in 1855, I thought it but just to offer him the opportunity of renewing an attempt to penetrate into Africa. I had no other reasons. I could not expect much from his assistance; he was not a linguist – French and Arabic being equally unknown to him – nor a man of science, nor an accurate astronomical observer.

9

This flatly contradicts Burton’s later admission that Speke had possessed ‘an uncommonly acute eye for country – by no means a usual accomplishment even with the professional surveyor’. It is, of course, inconceivable that Burton would have chosen someone to accompany him on the most important journey of his life, simply because he had suffered misfortune on an earlier occasion. If a better-qualified man had been available, Burton would have chosen him without hesitation. But Speke had much to offer. Even after they had fallen out, Burton would still feel compelled to praise his ‘noble qualities of energy, courage and perseverance’, and would pay tribute to his skill in ‘geodesy’, demonstrated by his use of a watch, the sun and a compass to fix the position of geographical features on a map.

10

Burton also knew that Speke understood how to measure the moon’s position, relative to other stars, in order to determine longitude – another exceptionally useful accomplishment. But perhaps what weighed most with him was his memory of the miraculous way in which Speke had escaped what had looked to be certain death. This feat had required outstanding physical fitness, and an unbreakable will.

Such qualities apart, what did Burton think of him as a person? Certainly, Jack Speke was not as well educated as he was, neither having been to a university nor having written books and mastered numerous languages. Speke’s parents -though they could have afforded the fees of a leading public school – had sent him as a boarder to unremarkable Barnstaple Grammar School, fifty miles from their estate in Somerset. Like many of his contemporaries at famous schools, Speke did little work, often cutting class and preferring country pursuits to Latin and Greek.

11

But though his teenage delinquencies were no match for Burton’s youthful love affairs, the pair still had one significant formative experience in common. Both had grown up in households where the mother was the dominant parent.

Speke’s reclusive father, William, although rich and head of a family that had owned land in Somerset since Norman times, had refused to stand for parliament, even when urged to do so by William Pitt, the prime minister, who was a neighbouring landowner. All he asked was to be left in peace to manage his estate, as had generations of his stay-at-home forebears. This slightly dull county family was certainly not one that might have been expected to produce, out of the blue, a man destined to rip the veil from the heart of Africa. Jack was the second of William’s four sons, but would be the only one sufficiently favoured by his mother to be given her maiden name, Hanning, as one of his forenames. Indeed she always addressed him as Hanning, his second name, in preference to John or Jack.

12

Georgina was an heiress with ambitions for her family. In later years, when ‘Hanning’ went abroad, it would be she, rather than her husband, who would correspond with her favourite son’s publisher and with the RGS on his behalf.

13

In a letter to John Blackwood, his publisher, Speke describes ‘leaving the mammy strings … [for] the life of a vagabond’, implying that his journeying sprang from the need to escape his mother’s control.

14

Richard Burton’s equally strong-minded mother, Martha -besides influencing him more than his professional invalid of a father – was fascinated by young tearaways like her remittanceman

half-brother – another Richard Burton. Her son Richard definitely believed that his own ‘madcap adventures … developed a secret alliance between them … Like all mothers she dearly loved the scamp of the family.’

15

Georgina Speke also seems secretly to have admired high-spirited misbehaviour. A curious passage was deleted by Blackwood from the proofs of Speke’s first book, in which the explorer advised an African monarch how to increase his chances of impregnating his wives. The young ruler, he suggested, should limit the number of times he had sex and ‘refrain from over-indulgences, which destroy the appetite in early youth’. There were plenty of youths in Europe and elsewhere, Speke explained, who, ‘because of the foolish vanity their mothers and nurses have of having forward boys increase their veins in size by over-exertion, and thereby decrease their power’.

16

The routine depiction of Speke by Burton’s biographers as a dullard, with no interest in sex, is given the lie by dozens of risqué passages cut by Blackwood from proof versions of his books. Speke described the cuts disapprovingly as ‘this gelding business’.

17

‘If you persist in gelding me,’ he told Blackwood, ‘I shall think you more barbarous than even the Somalis.’

18

Nevertheless, Fawn Brodie, one of Burton’s most respected biographers, stated that ‘Speke at thirty-three was inhibited and prudish’.

19

In fact, aged thirty-three he wrote to an officer friend, describing in graphic detail how Somali women’s vaginas were ‘stitched across to prevent intrusion until the bridegroom feels inclined to consummate the marriage’.

20

Speke is said by one biographer to have accused Burton of making sexual advances to him. The evidence is flimsy.

21

Certainly Burton was possessed by a passionate sexual inquisitiveness, and had probably had homosexual experiences in India, but he had also kept Indian mistresses and had loved one of them deeply.

22

Nor did he suddenly lose interest in women while in Africa. On arrival in Aden, after the Berbera disaster, he had been found by the Acting Civil Surgeon to be suffering from syphilis caught from prostitutes in Egypt.

23

And Speke’s behaviour towards

African women in Uganda will show that he too was by no means devoid of heterosexual feelings.