Gallipoli (71 page)

Authors: Peter FitzSimons

Captain Gordon Carter and his men of the 1st Battalion also move forward, ready to make their assault. To Carter's amazement, when the time comes to charge over open ground, they suffer few casualties, as the Turkish fire has died down by now, and they are soon able to join their comrades pushing forward in the Turkish trenches, battling the Turks as they go and trying to ignore the puddles of Australian blood that abound. It is going to be a long night, for those that make it to sun-up.

Two hours after the attack at Lone Pine has begun, with the situation still not clear, Charles Bean, worried about Jack, decides to head to the northern section of the perimeter, where the Breakout is due to be made. On the way, he comes across some of Jack's comrades, who tell him that his brother has been shot once more! Mercifully, however, again it looks like he is going to live, as instead of a shot to the head, heart or abdomen â all of which are near-certain death sentences â he has suffered a shrapnel wound to his right hand and wrist, badly shattering them. The main thing is he has been safely evacuated to the beach.

Strange. In peacetime Australia, Charles Bean would have been devastated to hear such news. In wartime Gallipoli, there can be little doubt that Jack is one of the lucky ones, because it will get him out of the firing line, and Charles Bean is proud that the wound has come honourably.

By 8.30 pm, the situation at Lone Pine is partly stabilised, as the Australians are in possession of the first three rows of Turkish trenches, and have been able to place heavy sandbag walls between themselves and the now massing Turks on the other side, yet no one is under any illusions. Everyone knows the battle will continue as the Turks launch counter-attack after counter-attack, and the call for stretcher-bearers is heard throughout a black night now shattered by the roar of rifles and machine-guns, the screams of dying men, and the regular explosions of artillery shells and bombs.

Though pleased so far with what has been achieved, General Birdwood is shocked at the number of deaths: âGod forbid that I should ever again see such a sight as that which met my eyes when I went up there: Turks and Australians piled four and five deep on one another. The most magnificent heroism had been displayed on both sides.'

75

(The danger of the position is emphasised for General Birdwood when he foolishly puts the top of his head above the parapet for the split instant necessary for a Turkish bullet to give him a new part in his hair. âIt was lucky,' he would reminisce ever afterwards, showing off his scar, âthat I am not a six-footer.')

76

As to the carnage before him, Charles Bean feels the same as Birdwood. âThe dead lay so thick,' he would write later, âthat the only respect which could be paid to them was to avoid treading on their faces.'

77

That rather wistful figure strolling along the beach at Imbros? It is General Hamilton, gazing contemplatively at the last of the departing flotilla bearing the 11th Division, gliding away in the gathering dusk, to soon be swallowed by the gloom. âThe empty harbour frightens me. Nothing in legend stranger or more terrible than the silent departure of this silent Army, K.'s new Corps, every mother's son of them, face to face with their fate.'

78

âPUSH ON!'

The extreme difficulty of the ground which the Left Assaulting Column [which included Monash's 4th Brigade] was to traverse can hardly be exaggerated. It is mad country ⦠The 4th Brigade, through no fault of its own, was unquestionably in the worst state of all the ANZAC brigades.

1

James Rhodes, Gallipoli

I am sorry, boys, but the order is to go.

2

Colonel Brazier

6 AUGUST 1915, NORTHERN ANZAC, THE SILENT MARCH TO THE NORTH

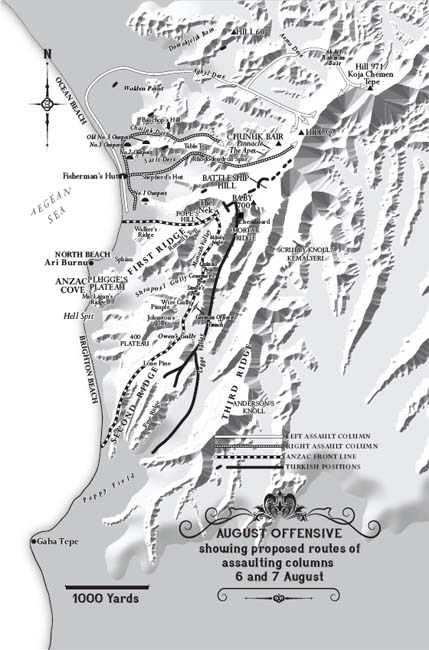

As the bloody distraction at Lone Pine continues, the four columns of troops who have been secreted in the gullies and on the slopes of spurs hidden from the Turks at Anzac are finally ready to launch their left-hook advance. It is not going to be easy, as this is the roughest of terrain in the entire Anzac sector. In fact, its rambling ravines and steep cliffs provide such a strong natural defence, Turkish soldiers are only thinly scattered at fortified outposts and unconnected sections of trenches instead of forming a continuous frontline, as with the southern two-thirds of their Anzac front.

At 8.30 pm, the Right Covering Force â made up of men from the New Zealand Mounted Rifles Brigade â are the first to move out, and they start winding inland along the gullies just to the south like a silent snake. Their job is to clear the way for the much larger Right Assault Column and capture the Turkish Old Number Three Outpost, plus other high points that lie on the spurs on the way up to Chunuk Bair.

August Offensive, by Jane Macaulay

As they go â just as has happened every night for a while now at around 9 pm â the destroyer

Colne

sails close to the shore and begins to shell that Old Number Three Outpost. Used to it by now, the Turkish soldiers there retreat as per custom to their shelters at the rear, while only 40 or so stay in the forward trenches.

The Aucklanders who are assigned to attack this, the strongest of the Turks' outposts, arrive as the shelling pours down, their footsteps muffled by the bombardment. The ruse has worked perfectly.

As planned, the shelling ceases at exactly 9.30 pm, at which point it is the Aucklanders themselves who explode, charging forward with a cheer straight at the Outpost. Some of them veer off, hooking around to the rear to bayonet any resistant Turks, while throwing bombs after those who flee. In short order, 100 Turks lie dead and a few are taken prisoner, while the Aucklanders have lost only seven men with 15 wounded.

This section of the Right Covering Force has accomplished its mission. The other hills and posts are not yet taken, however. And though the New Zealanders are progressing towards the objective, any delay is worrying. Time is of the essence, so that the Right Assault Force can move through here in the dead of night on their way up to Rhododendron Ridge and Chunuk Bair beyond.

Just an hour after their Shaky Islander comrades have marched out, the Left Covering Force, made up of British soldiers, begins its own silent march further northward along the beach, with the same kind of task â to clear the way for the Left Assault Column.

A right hook, followed by a left hook. It

must

destroy the enemy defences!

It has already been a long day for General Otto Liman von Sanders, but it is about to become longer still. At around 9 pm, he receives a telephone call informing him that âfrom the beach at Ari Burnu [Anzac] the enemy is moving northward along the coast â¦'

3

Immediately he calls Colonel Fevzi at Saros, some 35 miles to the north-east, telling him to ready his battalion: âBe prepared and make ready to march at once.'

4

Around 9.30 pm, Bean is still eager to get to the northern section of the perimeter, where the true thrust of the night is due to take place. It is from here that General Godley is to command the Right and Left Assault Columns, who are about to start their advance to seize the high ground of the Sari Bair Range.

The Right Assault Column is made up of men of the New Zealand Infantry Brigade, under the overall command of Brigadier-General Francis Johnston, who ⦠is a growing problem. Just how this alcoholic manages to access a seemingly never-ending supply of drink is never clear. What is apparent is that it now seems to be affecting his decision-making, or lack thereof.

âHe sat for hours in absolute silence,' his staff officer, Brigade-Major Arthur Temperley, would later write of Johnston's behaviour over this time period, âhe was frequently barely coherent and his judgement and mind were obviously clouded.'

5

And yet never do his men need more leadership than tonight. The job of the New Zealanders is to move up past the outposts already secured by their comrades of the Right Covering Force, and then on to Rhododendron Ridge and all the way to the heights of Chunuk Bair, likely against heavy resistance.

At their heart lies the Wellington Infantry Battalion, under the strong if gruff leadership of that fine officer from Taranaki, Lieutenant-Colonel William Malone. As he had recorded in his diary two days earlier, though, he is worried as to the state of his men's health. âWe are pleased to be moving, but the men are rundown and the reinforcement men are in a big majority, so I'm not too sanguine about what we can do.'

6

And the men of the other battalions are in not much better shape. Their numbers are dangerously low, and many are sick and broken, any trace of their joy for life now lost from their vacant stares and shuffling gait.

Malone is aghast that Johnston would volunteer such men for this momentous task, even when Birdie himself has âsaid the [New Zealand Infantry Brigade] had had so much hard work and had been so knocked about that it should not go out'.

7

Beyond that, Johnston's whole manner worries Malone. âHe is too airy for me ⦠He seems to think that a night attack and the taking of entrenched positions without artillery preparations is like “kissing one's hand”. Yesterday he burst forth: “If there's any hitch I shall go right up and take the place myself.” All, as it were, in a minute and on his own! He says, “There's to be no delay.” He is an extraordinary man. If it were not so serious, it would be laughable. So far as I am concerned, the men, my brave gallant men, shall have the best fighting chance I can give them ⦠No airy plunging â¦'

8

Malone also fears deeply that his own fate may not be a happy one. Just an hour before he starts the night advance, he had written a letter to his beloved wife, Ida, in case anything should happen to him:

I expect to go through all right but, dear wife, if anything untoward happens to me, you must not grieve too much, there are our dear children to be brought up. You know how I love and have loved you.

9

And now, as he is to move out, he cannot help but write once more, signing his letter:

My candle is all but burnt out and we will soon be moving. So good night, dearest one. With all my love. Your lover and husband. XXX

.

10

As Charles Bean arrives at General Godley's HQ at Number Two Outpost, the men of the Left Assault Column are on the move. They are being led out by Brigadier-General Monash's 4th Brigade, who are said to be âthe least healthy of all the Australian brigades'.

11

As soldiers march by outside, all their bayonets âwrapped in hessian to obviate glint' for when the sun rises

12

â

far and near, low and louder, on the roads of earth go by

â Bean lopes over to where Godley is standing and hears him ask one of his officers, âCan I tell Army Corps that both the Brigades have cleared this place?'

13

The officer goes outside to check, and comes back to report that the troops passing are those of Brigadier-General Monash, his stretcher-bearers, to be precise.

âThen I can say both Brigades are past here?'

âNo, no, Sir, the Indian Brigade is only arriving.'

âWhat, are they behind Monash? Good God!'

âBut that was the order they were told to go in, Sir.'

14

Godley gives a small nod, as if to say âvery well then'.

Bean is stunned. This is the General in charge of the whole operation, and yet on something as basic as which order his troops are due to leave in, he is mixed up?

Bean needs a drink, and perhaps Godley does too, for the two share some of the General's whisky before Bean heads off into the darkness with the column of Indian soldiers, eager to catch up with Monash. As he goes, Godley calls after him in his plummy English accent, âTell him to hurry up.'

15

The lanky journalist lets out a small, almost defeated sigh as he walks further into the darkness. Striding past the column of troops, whose movement is slowed by the gear on their backs, he has not gone far when he hears shots coming from a different direction, from a long way off.

From the direction of Suvla Bay?

Likely. The landing must have begun â¦

And then come more shots, from much nearer, as the Turks gather themselves to strike back at the columns of Anzacs heading up the gullies. As Brigadier-General Monash, with his troops up ahead, records, âWe had not gone half a mile when the black tangle of hills between the beach road and the main mountain-range became alive with flashes of musketry, and the bursting of shrapnel and star shell, and the yells of the enemy and the cheers of our men as they swept in, to drive in the enemy from molesting the flanks of our march.'

16

As the firing goes on, Bean continues to move forward regardless, when suddenly he feels âa whack, like a stone thrown hard, in the upper part of the right leg'.

17

Has he been hit by a stray bullet or piece of shrapnel?

Very likely. But there doesn't seem to be any blood, so perhaps whatever it was has not penetrated â or maybe the whisky has numbed him to everything. And yet, a short time later when he again puts his right hand inside his pants, it comes away sticky and greasy. He

has

been hit, and the wound is bleeding profusely.

Very reluctantly â like brother Jack, aware that it could have been much worse â he leaves Monash and his men to their own devices and starts limping back, to either get to an aid post, where he can get some treatment, or to his dugout, which lies just near the Headquarters of ANZAC Commander General Birdwood.

10 PM, 6 AUGUST 1915, AND SO IT BEGINS AT SUVLA BAY

There are thousands of them.

Aboard a silent armada of ten destroyers with ten of the black âbeetle lighters' in tow, 11,000 soldiers of the first wave of General Stopford's 11th Division are now approaching the shores of Suvla Bay. The landing is under the control of Commander Edward Unwin of

River Clyde

infamy, and how can he not help but compare this time to the last? If only they had had these beetles at Cape Helles.

Still, despite there being a strong force now lining up on the destroyer to climb down into superb landing craft with drawbridges that will drop as soon as they hit the shore, there is some nervousness among these raw soldiers of Kitchener's all-volunteer New Army as to what to expect from their first action. Their anxiety is heightened, as one soldier would recall, by looking at his own ship's superstructure: âThere were patches on her squat funnels and bullet-holes on her bridges. And what were those dark stains upon her decks?'

18

Now if the first of the 5000 British soldiers in the beetles don't quite âstorm ashore', at least they come on like a very strong breeze, and there is actually no reason to do anything else. Compared to what had been waiting for them at Cape Helles, the Turkish defences in these parts really are minimal. In fact, these men come âashore ⦠on undefended beaches'.

19

Atop the two hills overlooking Suvla Bay â Hill 10 at the east and Lala Baba at the south â the 1500-odd men of two Ottoman Gendarme Battalions first shoot up flares to illuminate those now crammed onto the beach and then open fire. Hill 10 pours down mortar shells, while those on Lala Baba fire their rifles.

Though Lala Baba falls quickly, Hill 10 does not. Like the mouse that scares the elephant, the Turks manage to keep up heavy fire on these strangely quiescent British troops, who display no dash, no daring, no derring-do. In the darkness, there is chaos on the heavily crowded beach as units are mixed up, and the shots that are fired by the few Turkish defenders all seem to find their mark. No one on the beach seems to know which hill they are meant to take and what their precise orders are. In the hurly-burly of it all, the general plan â to push east into the hills and then south to join hands with elements of the Left Assault Column trying to dominate the peaks of the Sari Bair Range â is lost sight of.

General Stopford? He is aboard his sloop, HMS

Jonquil

, somewhere well offshore. (In fact, far enough offshore that they can hear very little firing and assume that the forces have landed unopposed. General Stopford goes to sleep.)