Intelligence in War: The Value--And Limitations--Of What the Military Can Learn About the Enemy (45 page)

Authors: John Keegan

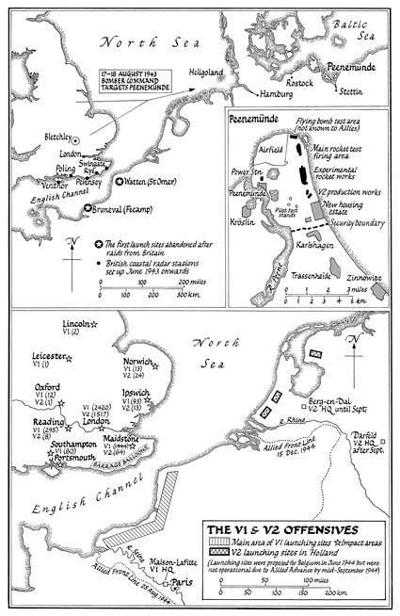

The bombing proved fruitless. General Erich Heinemann, the German commander of V-1 and V-2 launch units, had always suspected that the ski sites were both too conspicuous and too vulnerable and, after the December attack, decided to abandon them and build at other places, where he laid little more than foundations, the structures to be completed from prefabricated parts at the last moment. He also gave up the large storage structures, making use of natural caves to house his stocks of secret weapons and fuel. As a deception measure, however, some repair work was done at the ski sites, while security was screwed even tighter. The result, for the Germans, was highly satisfactory. Though the sixty-six modified sites were eventually identified, by photographic reconnaissance and from agent reports, intelligence officers failed to persuade their operational superiors that attacks were deserved. It was felt that enough had been done by the bombing of the ski sites, and that the “modified sites” could be attacked if and when a pilotless weapon bombardment started. Only one attack, by fighter bombers, was launched, on 27 May.

The threat, however, had not gone away. On 10 June a Belgian source reported the passage of a hundred “rockets” by rail through Ghent towards the Franco-Belgian frontier; on the 11th new photographic intelligence revealed “much activity” at six of the modified sites, with rails being laid on ramps and buildings completed. On 12 June the British Assistant Chief of the Air Staff (Intelligence) warned the Chiefs of Staff that the Germans were making “energetic preparations to bring the pilotless aircraft sites into operation at an early date.” The next day the first flying bomb fell on London. They would continue to do so until 14 January 1945.

Gun, fighter and balloon defences, deployed to a well-thought-out plan, achieved a measure of success from the outset. On 15 June, 244 flying bombs were launched but by the 21st the guns and balloons were bringing down 8 to 10 a day, fighters 30 a day, and, also because of technical faults, only about 50 a day were reaching London. By July the number had fallen to 25, by August, on one day, 14. The decrease in the number was largely due, however, to the overrunning of the launch sites as the Allied Liberation Armies advanced along the French coast. After 1 September, when Luftwaffe Regiment 155 (W) withdrew to Belgium and then Holland, most flying bombs launched against Britain were dropped from a mother aircraft. On 24 December 1944, fifty aircraft released flying bombs against Manchester, of which thirty crossed the coast and one reached the target.

It nevertheless caused more than a hundred civilian casualties. The V-1 was a highly effective weapon, hated and rightly feared by Londoners and the residents of other British cities it reached. Its approach was signalled by its distinctive pulse-jet beat, the beginning of its descent by silence, its impact by a major explosion. Because of its low terminal speed, it caused destruction over a wide area and heavy loss of life. Deaths inflicted by flying bombs are estimated at 6,184, the severely injured at 17,987. In all, 8,892 flying bombs were launched against Britain from ground ramps and 1,600 from aircraft, of which 2,419 reached the London Civil Defence Region (25 to 30 reached the ports of Southampton and Portsmouth and one Manchester) and another 1,112 landed on English soil; 3,957 were destroyed in flight, by fighters and guns about equally. Balloon barrages intercepted 231. Much of the success of the guns was due to the delivery from America of proximity fuses for their shells, devices which incorporated a miniature radar set, detonating the charge when a target was detected within effective range.

30

THE V-2 SUCCEEDS THE V-1

By early September 1944 the British Chiefs of Staff had reason to believe that the pilotless weapon threat had passed. All launching sites within the flying bomb’s known range from London had been overrun. The belief was ill-founded. The Germans would shortly turn to air launching, while Peenemünde was developing a lighter version of the V-1 that could reach England from German sites. Nevertheless, the Chiefs of Staff estimate was approximately correct. Only 235 air-launched flying bombs eluded the defenders and only 91 of the lighter model. Some caused heavy casualties; but the flying-bomb offensive was rightly judged to have passed its peak by early September.

Almost immediately, however, Peenemünde’s other gift to Hitler’s promise of retaliation by revenge weapons made its appearance. At 6:43 p.m. on 8 September 1944 a rocket—later known to have been launched from The Hague, in Holland—fell at Chiswick, in London, killing or seriously injuring thirteen people. A second rocket fell sixteen seconds later in Epping Forest, east of London, but caused no casualties.

The explosions might have been mistaken for those of flying bombs; but there had been no visual or radar observation of that missile, whose characteristics were by then all too well known. Moreover, very late in the day, the British intelligence establishment had at last accepted the reality of the threat. At a meeting held on 18 July, with the Prime Minister in the chair, R. V. Jones presented a paper summarising what was known of the rocket so far. The evidence consisted of reports by the Poles from Blizna of rocket firings, of similar reports from Peenemünde, of Enigma decrypts of German signals reporting flight details observed and, most tellingly, of physical evidence of a rocket misfired into Swedish territory on 13 June. Two British technical experts had been allowed to inspect the wreckage, which had subsequently been shipped to London. It was a baffling consignment, since the V-2 concerned had been used as the carrier for an experimental Waterfall anti-aircraft rocket; but the wreckage was complete enough to reveal that the rocket contained a turbo-compressor; which pointed to liquid fuel, internal guidance vanes and some radio-control equipment. Taken together, the evidence suggested that the Germans had fired between thirty and forty rockets in June and that the missile had reached a state of development “good enough, at least for a desultory bombardment of London.” Churchill was furious. “We have been caught napping,” he burst out, banging the table.

31

He had some reason for displeasure. Lord Cherwell’s doctrinaire dismissal of the feasibility of a rocket had caused delays; so, later on, had the tendency, typical of all intelligence bodies, for some of those involved to withhold evidence from others, on the grounds that they wished to be sure of its significance before passing it on. It was also seen, later, that not enough credibility had been attached to evidence extracted by interrogation from two prisoners of war. Eventually, too, it was realised that photographs of Peenemünde had shown rockets in their firing positions as early as 1943; they had simply not been recognised for what they were, being mistaken for “towers” connected with launching, instead of being seen as V-2s standing on end.

At the same time, it can be seen in retrospect that the British intelligence experts might be forgiven. Their fault was not obtuseness but ignorance, the result of a quite remarkable aeronautical backwardness in both Britain and the United States. Aeronautical science in both countries had achieved great success during the pre-war and war years in designing and developing highly successful fighters and bombers—of an entirely conventional type. While they, however, were building the Spitfire, Flying Fortress, Lancaster, Mosquito and P-51 Mustang, the equal or superior of their German equivalents, and the means by which Germany’s cities were flattened during the strategic bombing offensive and the bomber fleets which achieved the devastation were defended, the Germans were achieving a higher and quite revolutionary level of design and development. Between 1936 and 1944 they built and flew the first practical helicopter (the Focke-Achgelis FW-61), the first turbo-jet aircraft (the Heinkel He 178), the first cruise missile (the FZG-76 or V-1) and the first extra-atmospheric rocket (the A-4 or V-2).

32

It was an astonishing achievement, largely conducted in complete secrecy. Only the small size of Germany’s industrial base, compared to that of the United States, prevented it from dominating the skies during the Second World War.

Of all four achievements, helicopter, jet aircraft, cruise missile, rocket, the development of the V-2 was by far the most impressive. While Lord Cherwell, a scientist of formidable intellect, was denying that a liquid-fuelled rocket was feasible, Wernher von Braun was already perfecting his fourth model of such a missile. Having begun as a schoolboy enthusiast, working entirely alone, he had engaged the support of the German army, secured funds from the German state, learnt how to generate and control huge volumes of hot gas produced by the combustion of liquids, how to insert guidance devices in the exhaust and how to moderate his rocket’s rate of ascent until it could achieve a ballistic trajectory dirigible by an on-board guidance system. Between 1932 and 1942, when the first successful test firing of the A-4 was staged, it is no exaggeration to say that von Braun, still only in his thirtieth year, invented what would become both the intercontinental strategic ballistic missile and the space rocket.

Little wonder that the British scientific intelligence establishment of 1943–44, still fixed in the belief that rockets could only be propelled, and then for short distances at low speed, by solid fuel, were left to flounder among the miasma of vague agent reports, inexplicable air photographs, Enigma scraps, ill-informed prisoner-of-war interrogations which was all the intelligence machine supplied, seeking a focus. Lacking as they did the scientific and technical knowledge then enjoyed in abundance by their enemies, it is not surprising that the experts were “caught napping.” They did not know, could not imagine what it was for which they were looking. They were like men from the age of the mechanical calculator striving to perceive the nature of the electronic computer.

It was very fortunate for the British that the later stages of the V-2’s development proved fraught with difficulty for the Germans. Having supervised a perfect flight—with a missile not burdened by a warhead—as early as 3 October 1942, when an A-4 performed its characteristic slow-motion departure “as if being pushed by men with poles” before tilting gracefully into a ballistic trajectory and disappearing from sight at 3,000 mph, von Braun thereafter was racked with difficulty. Towards the end of 1943, when the rocket was approaching the production stage, it became apparent that between 80 and 90 per cent of firings ended in failure. Sometimes the rocket would fall back to earth at the firing point or explode when it had reached a height of only 3,000 feet, or would disintegrate on re-entering the atmosphere, or would split above the impact area, leaving the body behind while the warhead continued on course. Disintegration made assessment of the reason for failure very difficult (though providing the resistance fighters of the Polish Home Army with plentiful wreckage to forward to London; one Pole cycled 200 miles with components to reach an airstrip from which a liaison aircraft carried them back). The root of the trouble was mechanical: vibration caused breakages, particularly of electrical relays inside the rocket body. Re-entry caused shocks which broke its structure. Eventually, after 65,000 modifications, including a complete re-engineering of the nose cone containing the one-ton warhead, the rocket began to perform with reasonable consistency.

By then, however, the planned date for the inception of the “revenge” campaign had long passed. The flying-bomb operation had already been effectively defeated, by the capture of the sites from which it was launched; brilliantly effective though the V-1 was as a cheap and simple weapon, it suffered from the limitation of short range and its need for a static launching platform. The V-2 was potentially much more difficult to neutralise. Its complexity and high cost were offset by the simplicity of its launch system, which allowed it to depart from any point where a few square feet of hard surface to sustain the thrust of its exhaust gases could be built or even found. Indeed, in some respects, the Meillerwagen, which both transported the weapon and raised it to the vertical, was as brilliant a conception as the rocket itself. Variants remain a key component of all medium-range ballistic missile systems today.

The V-2’s only physical vulnerability lay in its operating crew’s dependence on storage facilities and certain ancillary factories. Its production, centralised in the underground works at Nordhausen in the Harz Mountains, staffed by slave workers, was impervious to bombing; the roof was 300 feet thick. Its existence, moreover, was not discovered until late 1944, and it was recognised as an unprofitable target. When, therefore, in late July 1944 the British at last became aware of the V-2 threat, the only means available to reduce it were seen to be bombing attacks on the rocket storage centres and on the facilities producing its key constituents, particularly liquid oxygen. By then, however, most of the “large sites,” as they were known to British intelligence, had already been heavily bombed and severely damaged; in any case, loss of bases in France and Belgium soon forced the V-2 units back into Holland, where, as General Dornberger had always wished, they operated from improvised sites supplied from centres deeper inside Germany on a hand-to-mouth basis. The German retreat forced the early abandonment of the two main liquid oxygen supply sources, at Liège in Belgium and Wittringen in the Saar, reducing the Germans to dependence on smaller sites difficult to identify and locate.

33