Meatonomics (32 page)

Authors: David Robinson Simon

Many studies show that egg consumption increases blood cholesterol, a phenomenon linked to increased risk of heart disease.

35

On the other hand, a well-publicized 2007 paper by Adnan Qureshi and colleagues found that adults who eat more than six eggs per week have no greater risk of stroke or heart disease than those who eat no eggs.

36

While some point to the first set of studies to argue that eggs cause heart disease, others—notably, the egg industry—cite the Qureshi article as evidence of eggs' harmlessness. Because this study's design and methodology are similar to those of other inquiries finding that animal foods are healthy, such as the Siri-Tarino piece discussed in

chapter 1

, it merits a closer look.

Using the cohort research model, Qureshi's team compared several populations of egg eaters to determine their incidence of disease

over time. Qureshi's team adjusted for confounding factors like age, gender, race, and cigarette smoking. But just as the Siri-Tarino researchers did, the Qureshi team failed to adjust for the most important confounding factor: regular consumption of other animal foods. American males over the age of twelve routinely consume more cholesterol than recommended, in some cases by 100 milligrams or more daily.

37

Since many Americans are

already

in a high-cholesterol category, which leads to heart disease for one in three, it's easy to see why adding an egg a day might not materially increase this risk.

In fact, in order to make their analysis representative of the US population, the Qureshi team

chose

cohorts whose members were overweight (with BMI over 25)

and

had blood cholesterol levels of 220 mg/dl or higher. That's 10 percent above the recognized safe cholesterol level of 200 mg/dl and 50 percent higher than the average of 146 mg/dl among vegans.

38

In other words, this study looked at whether overweight people with high cholesterol, already substantially at risk for heart disease, would get any worse if they ate an egg a day. That's like studying the risk of cigar smoking among people who already smoke two packs of cigarettes a day.

Dietary cholesterol is present in animal foods but not in plant foods. So the only accurate way to measure the cholesterol-related effects of eating eggs is to compare a cohort of vegans with one whose only source of dietary cholesterol is eggs. Since the Qureshi study failed to control for the confounding effects of cholesterol intake, it's little wonder the study found no difference in disease risk between groups.

On the other hand, researchers

do

find a link between egg consumption and disease when they compare cohorts who eat less animal foods than Americans do and for whom a single egg is thus a more significant part of their diet. One study involving Japanese cohorts noted health benefits associated with “limiting egg consumption.”

39

These researchers found links among egg consumption, blood cholesterol levels, and mortality rates among women “in geographic areas where egg consumption makes a relatively large contribution to total dietary cholesterol intake.”

40

Plainly stated, the harmful effects of eggs

are more clearly evident among those who eat less animal foods to begin with.

Despite the Qureshi study's design flaws, it's a favorite among egg industry marketers. The American Egg Board receives $21 million in yearly federal-mandated checkoff money.

41

These funds power the website

eggnutritioncenter.org

, where the Qureshi study gives credibility to misleading messages like “An Egg a Day is MORE Than Okay!”

42

Not to get too metaphysical, but is it possible to discuss eggs without mentioning chicken? Actually, chicken-related illnesses like cancer, heart disease, and food poisoning are discussed in the main text. As shown in

chapter 6

, there's little that's healthy about chicken.

Like eggs, fish are a nutritional paradox. On one hand, they're a good source of omega-3 fatty acids, which can improve infant brain development and reduce the risk of coronary heart disease.

43

On the other hand, almost without exception, fish contain mercury, a neurotoxin that can damage the nervous system and cause cognitive disabilities.

44

And they frequently contain polychlorinated biphenyls (PCBs), which cause cancer and, in infants, neurological and motor control problems.

45

Like all animal foods, fish also invariably contain cholesterol (in some cases at levels as high as ground beef—see

table 6.1

in

chapter 6

), and this substance causes heart disease. Finally, because

all

animal protein—including fish—promotes cancer, a diet high in seafood increases one's risk of cancer relative to a plant-based diet.

46

Where does all this mercury and PCB come from? The mercury seems to come mainly from coal-fired power plants. PCBs, on the other hand, were used in manufacturing in the United States until they were banned in 1977, but they've lingered in our water and soil for decades and, as a result, persist in the environment. Both PCBs and mercury accumulate in the fatty tissues of fish and other animals, which means they are passed up the food chain until eaten by humans.

In a seven-year study of fish in 291 US waterways, the US Geological Survey found that

every one

of more than one thousand fish

it examined contained some mercury. One-quarter of the fish contained mercury at levels unhealthy for human consumption, and two-thirds were contaminated at levels unhealthy for consumption by other mammals.

47

It's not just fish in inland waterways that are toxic with mercury; high levels of mercury are routinely found in deep-sea fish as well.

48

And PCBs are equally prevalent: another study found that thirty-nine of forty fish sampled contained PCBs in measurable quantities.

49

The nutritional paradox surrounding fish leads to complicated advice on whether and when to eat it, dispensed in articles with titles like “Fish Is Good—Fish Is Bad” and “Americans Confused about Health Effects of Eating Fish.”

50

In one particularly bizarre piece in the

Journal of the American Medical Association

, the authors note that omega-3s may help new or expectant mothers, but a few paragraphs later, warn that new or expectant mothers “should avoid four types of fish that are higher in mercury content.”

51

Other articles contain charts advising which fish have acceptable levels of mercury and PCBs and how often one can eat them.

52

If this seems like a lot of risk and effort to obtain omega-3s, consider a non-fish, nontoxic source for your beneficial fatty acids. Omega-3s are readily available in flax, hemp, soy, and walnuts. You won't need a chart to remember which you can eat and when, and none of these plant-based sources causes cancer, neurological defects, or developmental impairment.

¶

Milk, the source of all dairy, is the main ingredient in cheese, butter, cream, ice cream, yogurt, and whey.

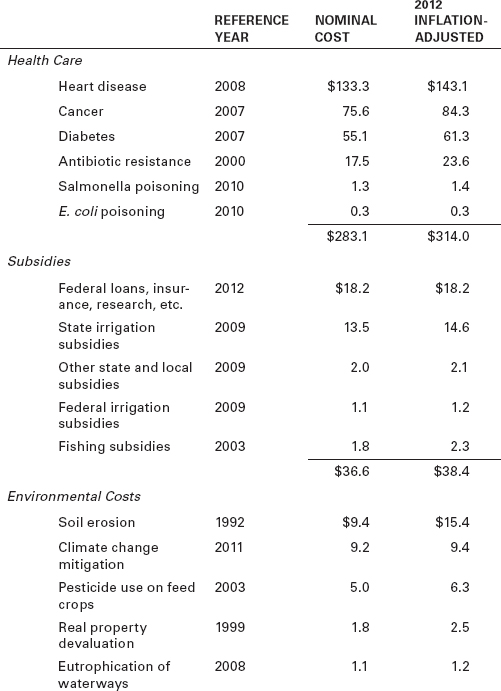

Summary of the Annual Externalized Costs of US Animal Food Production (in billions)

1

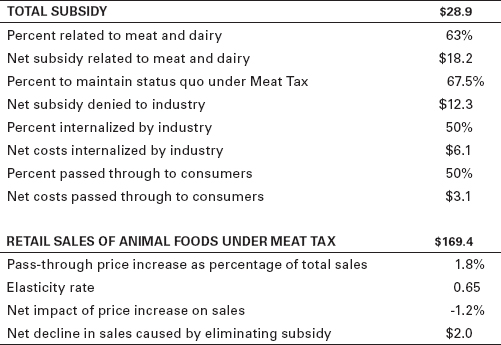

Economic Effects of Proposed Meat Tax and Support Changes

This appendix shows calculations for the main economic effects expected to result from this book's proposed changes to federal tax and support policy. These outcomes include: (1) reductions in subsidies and other support to the animal food industry, (2) a drop in consumption of animal foods, (3) a new tax burden for taxpayers, (4) a new tax credit for taxpayers, (5) an increase in tax revenue, (6) higher federal government outflows associated with the tax credit, (7) lower state and federal government outflows under Medicare and Medicaid programs, (8) a cash surplus for the federal government, and (9) decreases in externalized costs. As a reminder, economics is not a precise science, so while these figures may seem meticulously calculated, they are just estimates. You don't really know how something will play out until you try it, although you can certainly make predictions.

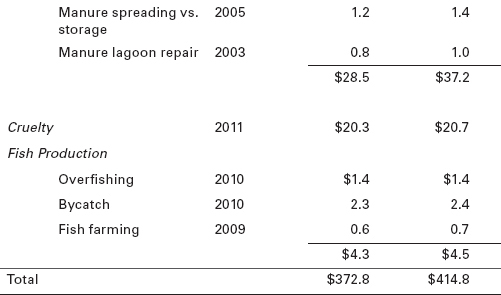

The following calculations use a constant of 0.65 as the price elasticity of demand for animal foods. This constant is a weighted average based on the individual fair market values of animal foods produced yearly and their respective price elasticities, as shown in

table C1

. Note that “production value,” roughly analogous to wholesale value, is used rather than retail value because retail sales data for individual animal foods is not uniformly available.

TABLE C1

Animal Food Production Values, Elasticities, and Weighted Average Elasticity Rate (dollar amounts in billions)

1

,

2

The proposed support changes affect two categories. First, there's the gross figure of $28.9 billion that the USDA spends supporting US farmers with loans, insurance, research, marketing assistance, and other help (the research and marketing subsidy).

3

My recommendation is to eliminate the portion of this subsidy related to animal food production, which is roughly $18.2 billion.

4

Loss of this subsidy will have an effect on both producers and consumers.

From the producers' perspective, because the Meat Tax will cause consumption (and production) of animal foods to decline by 32.5 percent (see “Drop in Consumption” below), the portion of this subsidy on which producers would rely in order to maintain the status quo after adjusting sales for the effects of the Meat Tax is 67.5 percent (1 – 0.325) of $18.2 billion, or $12.3 billion. In other words, following the drop in consumption, a subsidy of only $12.3 billion will allow producers to maintain production at the new, lower level.

In the absence of data predicting how producers are likely to respond to the loss of certain services, it is reasonable to assume that

they will choose to discontinue roughly half of these formerly subsidized services and continue half at their own expense ($6.1 billion). And in light of data showing that producers typically internalize some portion of increases in production costs (ranging from a minority to a majority of such costs), it is reasonable to assume further that producers will internalize roughly half of these costs and pass the other half ($3 billion) on to consumers.

5

The resulting price increase is roughly 1.8 percent of the total retail sales of animal foods, after reducing this sales figure for the effects of the Meat Tax (see “Drop in Consumption” below).

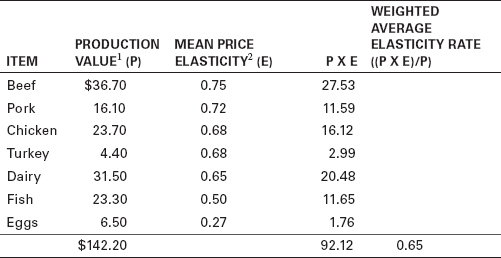

Table C2

shows the effect of applying the demand elasticity constant of 0.65 to this increase: eliminating this subsidy will cause consumer demand to decline by about 1.2 percent.

TABLE C2

Effects of Eliminating Research and Marketing Subsidy (dollar amounts in billions)