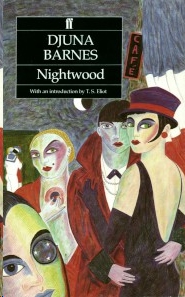

Nightwood

NIGHTWOOD

JEANETTE WINTERSON

INTRODUCTION BY

T. S. ELIOT

A New Directions Book

To

PEGGY GUGGENHEIM

and

JOHN FERRAR HOLMS

Certain texts work in homeopathic dilutions; that is, nano amounts effect significant change over long periods of time.

Nightwood

is a nano-text.

It is, in any case, not quite two hundred pages long, and more people have heard about it than have read it. Reading it is mainly the preserve of academics and students. Others have a vague sense that it is a Modernist text, that T. S. Eliot adored it, that Dylan Thomas called it “one of the three great prose books ever written by a woman,” (accept the compliment to DB, ignore the insult directed elsewhere), that the work is an important milestone on any map of gay literature—even though, like all the best books, its power makes nonsense of any categorization, especially of gender or sexuality.

Nightwood

is itself. It is its own created world, exotic and strange, and reading it is like drinking wine with a pearl dissolving in the glass. You have taken in more than you know, and it will go on doing its work. From now on, a part of you is pearl-lined.

In his Introduction, Eliot talks about the necessity of reading

Nightwood

more than once—because the second reading will feel very different to the first. This is true.

In our society, where it is hard to find time to do anything properly, even once, the leisure—which is part of the pleasure—of reading is one of our culture-casualties.

For us, books have turned into fast food, to be consumed in the gaps between one bout of relentless living and the next. Airports, subways, maybe half an hour at bedtime, maybe something with the office sandwich, isn’t really ideal. At least at the cinema, or at the theater, or at a concert, or even in a gallery, some real time has to be set aside. Books have been squeezed in, which goes a long way towards explaining why our appetite for literature is waning, and our allergic reaction to anything demanding is on the rise.

Nightwood

is demanding. You can slide into it, because the prose has a narcotic quality, but you can’t slide over it. The language is not about conveying information; it is about conveying meaning. There is much more to this book than its story, which is slight, or even its characters, who are magnificent tricks of the light. This is not the solid nineteenth-century world of narrative, it is the shifting, slipping, relative world of Einstein and the Modernists, the twin assault by science and art on what we thought we were sure of.

That is why, in

Nightwood

, Baron Felix represents a world that is disappearing. It is why he is so confused about the world he must live in, and why his son Guido is a kind of holy fool. As Gertrude Stein put it so well, “There is no there there.” You can read this twice—as a comment on matter, and a warning against consolation.

There is no consolation in

Nightwood

. There is a wild intensity, recklessness, defiance in the face of suffering. All the characters are exiles of one kind or another—American, Irish, Austrian, Jewish. This is the beginning of the modern diaspora—all peoples, all places, all change.

Djuna Barnes’s 1920s/30s Paris is a Paris on the cusp of leaving behind forever the haute world of Henry James, taken from Proust. That is a world where the better people dine in the Bois, and where open horse-drawn carriages still circle the park. It is in this world that the eager hands of Jenny Petherbridge first claw at Robin Vote, the American whom we meet passed out dead drunk in one of the new class of “middle” hotels, designed for a new kind of tourist—definitely not of the old world of servants and steamer trunks.

Seedy Paris of whores and cheap bars has not yet begun to change. It is to this world that Robin Vote is drawn; the night-time world, where she will not be judged, and where she can find the anonymity of a stranger’s embrace. This world is faithfully tracked and searched by Robin’s lover, Nora Flood, hunting faint imprints of her errant amour, sometimes finding her, collapsed with drink, and threatened by police, beggars, and women on the make.

It is a bleak picture of love between women. Jenny Petherbridge avid and ruthless. “When she fell in love it was with a perfect fury of accumulated dishonesty; she became instantly a dealer in second-hand and therefore incalculable emotions…. she appropriated the most passionate love that she knew, Nora’s for Robin. She was a ‘squatter’ by instinct.”

Nora Flood, “‘I have been loved,’ she said, ‘by something strange, and it has forgotten me.’”

Robin Vote “sitting with her legs thrust out, her head thrown back against the embossed cushion of the chair, sleeping, one arm fallen over the chair’s side, the hand somehow older and wiser than her body.”

Robin’s passivity, Jenny’s predatory nature, and Nora’s passionate devotion make an impossible triangle. The daily assaults of selfishness and self-harm do not offer a picture of love between women as anything safe or easy. A negative reading would sink us into the misery of the “invert,” the medical pathology of Havelock Ellis, and the bitterness of Radclyffe Hall and

The Well of Loneliness

(1928).

Djuna Barnes was well aware of these readings, and her own Paris community had its fair share of destroyed lives—think of Renée Vivien or Dolly Wilde. Djuna Barnes had spoofed the gay and not so gay times of her circle in

Ladies Almanack

, but if she was able to lampoon it—and that in itself is much healthier than Radclyffe Hall’s miserable mopings—then she was also able to celebrate it.

Nightwood

has neither stereotypes nor caricatures; there is a truth to these damaged hearts that moves us beyond the negative. Humans suffer, and, gay or straight, they break themselves into pieces, blur themselves with drink and drugs, choose the wrong lover, crucify themselves on their own longings, and let’s not forget, are crucified by a world that fears the stranger—whether in life or in love.

In

Nightwood

, they are all strangers, and they speak to those of us who are always, or just sometimes the stranger, or the ones who open the door to find the stranger standing outside.

And yet, there is great dignity in Nora’s love for Robin, written without cliché or compromise in the full-blown archetypal language of romance. We are left in no doubt that this love is worthy of greatness—that it is great. As the doctor, Matthew O’Connor, remarks, ‘“Nora will leave that girl some day; but though those two are buried at opposite ends of the earth, one dog will find them both.’”

“Grave” would have been a cliché, “dog” is a snapping stroke of genius. That’s how alive is the language of this text.

Robin, Nora, Jenny. Robin’s brief and disastrous marriage to Baron Felix, Felix’s own story of inferiority and loss, the underworld life of Paris, all are seen through the glittering eyes of a creature half leprechaun, half angel, half freak, half savant, half man, half woman, the “doctor,” Matthew-Mighty-grain-of-salt-Dante-O’Connor.

It is the doctor who first finds Robin Vote drowned in drink. The doctor who becomes the confidante of Felix, and urges him to carry his son’s mind “‘like a bowl picked up in the dark; you do not know what’s in it.’”

It is the doctor who talks his way through life as though words were a needle and thread that could mend it. When Nora finally comes to him, in the blackness of her despair, he talks her through it, alright, sitting up in his tiny iron bed, in a servant’s room at the top of a house, the slop bucket to one side, “brimming with abominations.”

The doctor is wearing full make-up, a nightgown, and a woman’s wig—he had been expecting someone else, but he begins his speech, as good as Molly Bloom’s soliloquy in

Ulysses

, and this episode is a linguistic, artistic, and emotional triumph. It matters that it is emotional.

Nightwood

is not afraid of feeling. It is not a glittering high-wire act, its pearls are deep-dived, and then dissolved into the language.

The best texts are time machines; they are of their moment, and can tell it, and they can take us back there later. But they are something more, too—they live on into the future because they were never strapped into time.

Most of what we hype is time-bound, and soon vanishes. Indeed, a good test of a work of art is that it goes on interesting us long after any contemporary relevance is dead. We don’t go to Shakespeare to find out about life in Elizabethan England; we go to Shakespeare to find out about ourselves now.

Djuna Barnes’s Paris is of its moment; yet

Nightwood

has survived not as a slice of history, but as a work of art. The excitements and atmosphere of her period are there, but there is nothing locked-in about

Nightwood

.

Readers in 1936, when

Nightwood

was published in Britain, would have been uncomfortably aware of Hitler’s rise and rise, and his notorious propaganda offensive at the Berlin Olympic Games—remember, Strength Through Joy?

It was the year of the British Abdication Crisis, when Edward VIII chose his American mistress, Wallace Simpson, over the English throne.

In America, other women were in the headlines—Margaret Mitchell published

Gone With The Wind

, and Clare Boothe Luce’s stageplay,

The Women

, was taking Broadway by storm.

It was also the start of the Spanish Civil War.

Nightwood

isn’t directly connected to any of this—a good example of why we must be careful of muddling up a work of art, or not one, with its subject matter.

Art isn’t rarefied or aloof, but it may have different concerns to the general—for instance, the Napoleonic Wars are never mentioned by Jane Austen, although she was living and working right through them.

Nightwood

, peculiar, eccentric, particular, shaded against the insistence of too much daylight, is a book for introverts, in that we are all introverts in our after-hours secrets and deepest loves.

Our world, this one now, wants everything on the outside, displayed and confessed, but really it cannot be so. The private dialogue of reading is an old-fashioned confessional, and better for it. What you admit here, what the book admits to you, is between you both and left there.

Nightwood

is a place where much can be said—and left unsaid.

For the rest of my life I will be climbing those stairs with Nora to the doctor’s filthy garret.

Why? Something of

Nightwood

has lodged in me.

It is not my story, or my experience, it is not my voice or my fear. It is, through its language, a true-shot arrow, a wound that is also a remedy.

Nightwood

opens a place that does not easily skin over.

There is pain in who we are, and the pain of love—because love itself is an opening and a wound—is a pain no one escapes except by escaping life itself.

Nightwood

is not an escape-text. It writes into the center of human anguish, unrelieved, but in its dignity and its defiance, it becomes, by strange alchemy, its own salve.

“‘Is there such extraordinary need of misery to make beauty?’” asks the doctor, but the answer is already written: Yes.

2006

Jeanette Winterson

When the question is raised, of writing an introduction to a book of a creative order, I always feel that the few books worth introducing are exactly those which it is an impertinence to introduce. I have already committed two such impertinences; this is the third, and if it is not the last no one will be more surprised than myself. I can justify this preface only in the following way. One is liable to expect other people to see, on their first reading of a book, all that one has come to perceive in the course of a developing intimacy with it. I have read

Nightwood

a number of times, in manuscript, in proof, and after publication. What one can do for other readers—assuming that if you read this preface at all you will read it first—is to trace the more significant phases of one’s own appreciation of it. For it took me, with this book, some time to come to an appreciation of its meaning as a whole.

In describing

Nightwood

for the purpose of attracting readers to the English edition, I said that it would “appeal primarily to readers of poetry.” This is well enough for the brevity of advertisement, but I am glad to take this opportunity to amplify it a little. I do not want to suggest that the distinction of the book is primarily verbal, and still less that the astonishing language covers a vacuity of content. Unless the term “novel” has become too debased to apply, and if it means a book in which living characters are created and shown in significant relationship, this book is a novel. And I do not mean that Miss Barnes’s style is “poetic prose.” But I do mean that most contemporary novels are not really “written.” They obtain what reality they have largely from an accurate rendering of the noises that human beings currently make in their daily simple needs of communication; and what part of a novel is not composed of these noises consists of a prose which is no more alive than that of a competent newspaper writer or government official. A prose that is altogether alive demands something of the reader that the ordinary novel-reader is not prepared to give. To say that

Nightwood

will appeal primarily to readers of poetry does not mean that it is not a novel, but that it is so good a novel that only sensibilities trained on poetry can wholly appreciate it. Miss Barnes’s prose has the prose rhythm that is prose style, and the musical pattern which is not that of verse. This prose rhythm may be more or less complex or elaborate, according to the purposes of the writer; but whether simple or complex, it is what raises the matter to be communicated, to the first intensity.