The Better Angels of Our Nature: Why Violence Has Declined (87 page)

Read The Better Angels of Our Nature: Why Violence Has Declined Online

Authors: Steven Pinker

Tags: #Sociology, #Psychology, #Science, #Amazon.com, #21st Century, #Crime, #Anthropology, #Social History, #Retail, #Criminology

BOOK: The Better Angels of Our Nature: Why Violence Has Declined

7.53Mb size Format: txt, pdf, ePub

FIGURE 7–3.

Hate-crime murders of African Americans, 1996–2008

Hate-crime murders of African Americans, 1996–2008

Source:

Data from the annual FBI reports of Hate Crime Statistics (

http://www.fbi.gov/hq/cid/civilrights/hate.ht

); see U.S. Federal Bureau of Investigation, 2010a.

Data from the annual FBI reports of Hate Crime Statistics (

http://www.fbi.gov/hq/cid/civilrights/hate.ht

); see U.S. Federal Bureau of Investigation, 2010a.

As lynching died out, so did antiblack pogroms. Horowitz discovered that in the second half of the 20th century in the West, his subject matter, the deadly ethnic riot, ceased to exist.

12

The so-called race riots of the mid-1960s in Los Angeles, Newark, Detroit, and other American cities represented a different phenomenon altogether: African Americans were the rioters rather than the targets, death tolls were low (mostly rioters themselves killed by the police), and virtually all the targets were property rather than people.

13

After 1950 the United States had no riots that singled out a race or ethnic group; nor did other zones of ethnic friction in the West such as Canada, Belgium, Corsica, Catalonia, or the Basque Country.

14

12

The so-called race riots of the mid-1960s in Los Angeles, Newark, Detroit, and other American cities represented a different phenomenon altogether: African Americans were the rioters rather than the targets, death tolls were low (mostly rioters themselves killed by the police), and virtually all the targets were property rather than people.

13

After 1950 the United States had no riots that singled out a race or ethnic group; nor did other zones of ethnic friction in the West such as Canada, Belgium, Corsica, Catalonia, or the Basque Country.

14

Some antiblack violence did erupt in the late 1950s and early 1960s, but it took a different form. The attacks are seldom called “terrorism,” but that’s exactly what they were: they were directed at civilians, low in casualties, high in publicity, intended to intimidate, and directed toward a political goal, namely preventing racial desegregation in the South. And like other terrorist campaigns, segregationist terrorism sealed its doom when it crossed the line into depravity and turned all public sympathy to its victims. In highly publicized incidents, ugly mobs hurled obscenities and death threats at black children for trying to enroll in all-white schools. One event that left a strong impression in cultural memory was the day six-year-old Ruby Nell Bridges had to be escorted by federal marshals to her first day of school in New Orleans. John Steinbeck, while driving through America to write his memoir

Travels with Charley

, found himself in the Big Easy at the time:

Travels with Charley

, found himself in the Big Easy at the time:

Four big marshals got out of each car and from somewhere in the automobiles they extracted the littlest negro girl you ever saw, dressed in shining starchy white, with new white shoes on feet so little they were almost round. Her face and little legs were very black against the white.The big marshals stood her on the curb and a jangle of jeering shrieks went up from behind the barricades. The little girl did not look at the howling crowd, but from the side the whites of her eyes showed like those of a frightened fawn. The men turned her around like a doll and then the strange procession moved up the broad walk toward the school, and the child was even more a mite because the men were so big. Then the girl made a curious hop, and I think I know what it was. I think in her whole life she had not gone ten steps without skipping, but now in the middle of her first step, the weight bore her down and her little round feet took measured, reluctant steps between the tall guards.

15

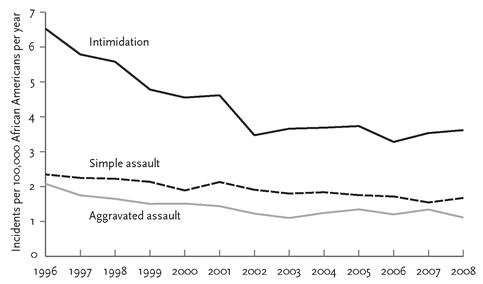

FIGURE 7–4.

Nonlethal hate crimes against African Americans, 1996–2008

Nonlethal hate crimes against African Americans, 1996–2008

Source:

Data from the annual FBI reports of Hate Crime Statistics (

http://www.fbi.gov/hq/cid/civilrights/hate.htm

); see U.S. Federal Bureau of Investigation, 2010a. The number of incidents is divided by the population covered by the agencies reporting the statistics multiplied by 0.129, the proportion of African Americans in the population according to the 2000 census.

Data from the annual FBI reports of Hate Crime Statistics (

http://www.fbi.gov/hq/cid/civilrights/hate.htm

); see U.S. Federal Bureau of Investigation, 2010a. The number of incidents is divided by the population covered by the agencies reporting the statistics multiplied by 0.129, the proportion of African Americans in the population according to the 2000 census.

The incident was also immortalized in a painting published in 1964 in

Look

magazine titled

The Problem We All Live With.

It was painted by Norman Rockwell, the artist whose name is synonymous with sentimental images of an idealized America. In another conscience-jarring incident, four black girls attending Sunday school were killed in 1963 when a bomb exploded at a Birmingham church that had recently been used for civil rights meetings. That same year the civil rights worker Medgar Evers was murdered by Klansmen, as were James Chaney, Andrew Goodman, and Michael Schwerner the following year. Joining the violence by mobs and terrorists was violence by the government. The noble Rosa Parks and Martin Luther King were thrown into jail, and peaceful marchers were assaulted with fire hoses, dogs, whips, and clubs, all shown on national television.

Look

magazine titled

The Problem We All Live With.

It was painted by Norman Rockwell, the artist whose name is synonymous with sentimental images of an idealized America. In another conscience-jarring incident, four black girls attending Sunday school were killed in 1963 when a bomb exploded at a Birmingham church that had recently been used for civil rights meetings. That same year the civil rights worker Medgar Evers was murdered by Klansmen, as were James Chaney, Andrew Goodman, and Michael Schwerner the following year. Joining the violence by mobs and terrorists was violence by the government. The noble Rosa Parks and Martin Luther King were thrown into jail, and peaceful marchers were assaulted with fire hoses, dogs, whips, and clubs, all shown on national television.

After 1965, opposition to civil rights was moribund, antiblack riots were a distant memory, and terrorism against blacks no longer received support from any significant community. In the 1990s there was a widely publicized report of a string of arson attacks on black churches in the South, but it turned out to be apocryphal.

16

So for all the publicity that hate crimes have received, they have become a blessedly rare phenomenon in modern America.

16

So for all the publicity that hate crimes have received, they have become a blessedly rare phenomenon in modern America.

Lynchings and race riots have declined for other ethnic groups and in other countries as well. The 9/11 attacks and the London and Madrid bombings were just the kind of symbolic provocation that in earlier decades could have led to anti-Muslim riots across the Western world. Yet no riots occurred, and a 2008 review of violence against Muslims by a human rights organization could not turn up a single clear case of a fatality in the West motivated by anti-Muslim hatred.

17

17

Horowitz identifies several reasons for the disappearance of deadly ethnic riots in the West. One is governance. For all their abandon in assaulting their victims, rioters are sensitive to their own safety, and know when the police will turn a blind eye. Prompt law enforcement can quell riots and nip cycles of group-against-group revenge in the bud, but the procedures have to be thought out in advance. Since the local police often come from the same ethnic group as the perpetrators and may sympathize with their hatreds, a professionalized national militia is more effective than the neighborhood cops. And since riot police can cause more deaths than they prevent, they must be trained to apply the minimal force needed to disperse a mob.

18

18

The other cause of the disappearance of deadly ethnic riots is more nebulous: a rising abhorrence of violence, and of even the slightest trace of a mindset that might lead to it. Recall that the main risk factor of genocides and deadly ethnic riots is an essentialist psychology that categorizes the members of a group as insensate obstacles, as disgusting vermin, or as avaricious, malignant, or heretical villains. These attitudes can be formalized into government policies of the kind that Daniel Goldhagen calls eliminationist and Barbara Harff calls exclusionary. The policies may be implemented as apartheid, forced assimilation, and in extreme cases, deportation or genocide. Ted Robert Gurr has shown that even discriminatory policies that fall short of the extremes are a risk factor for violent ethnic conflicts such as civil wars and deadly riots.

19

19

Now imagine policies that are designed to be the diametric opposite of the exclusionary ones. They would not only erase any law in the books that singled out an ethnic minority for unfavorable treatment, but would swing to the opposite pole and mandate

anti

-exclusionary,

un

-eliminationist policies, such as the integration of schools, educational head starts, and racial or ethnic quotas and preferences in government, business, and education. These policies are generally called

remedial discrimination

, though in the United States they go by the name

affirmative action

. Whether or not the policies deserve credit for preventing a backsliding of developed countries into genocide and pogroms, they obviously are designed as the photographic negative of the exclusionary policies that caused or tolerated such violence in the past. And they have been riding a wave of popularity throughout the world.

anti

-exclusionary,

un

-eliminationist policies, such as the integration of schools, educational head starts, and racial or ethnic quotas and preferences in government, business, and education. These policies are generally called

remedial discrimination

, though in the United States they go by the name

affirmative action

. Whether or not the policies deserve credit for preventing a backsliding of developed countries into genocide and pogroms, they obviously are designed as the photographic negative of the exclusionary policies that caused or tolerated such violence in the past. And they have been riding a wave of popularity throughout the world.

In a report called “The Decline of Ethnic Political Discrimination 1950–2003,” the political scientists Victor Asal and Amy Pate examined a dataset that records the status of 337 ethnic minorities in 124 countries since 1950.

20

(It overlaps with Harff’s dataset on genocide, which we examined in chapter 6.) Asal and Pate plotted the percentage of countries with policies that discriminate against an ethnic minority, together with those that discriminate in favor of them. In 1950, as figure 7–5 shows, 44 percent of governments had invidious discriminatory policies; by 2003 only 19 percent did, and they were outnumbered by the governments that had remedial policies.

20

(It overlaps with Harff’s dataset on genocide, which we examined in chapter 6.) Asal and Pate plotted the percentage of countries with policies that discriminate against an ethnic minority, together with those that discriminate in favor of them. In 1950, as figure 7–5 shows, 44 percent of governments had invidious discriminatory policies; by 2003 only 19 percent did, and they were outnumbered by the governments that had remedial policies.

When Asal and Pate broke down the figures by region, they found that minority groups are doing particularly well in the Americas and Europe, where little official discrimination remains. Minority groups still experience legal discrimination in Asia, North Africa, sub-Saharan Africa, and especially the Middle East, though in each case there have been improvements since the end of the Cold War.

21

The authors conclude, “Everywhere the weight of official discrimination has lifted. While this trend began in Western democracies in the late 1960s, by the 1990s it had reached all parts of the world.”

22

21

The authors conclude, “Everywhere the weight of official discrimination has lifted. While this trend began in Western democracies in the late 1960s, by the 1990s it had reached all parts of the world.”

22

Not only has official discrimination by governments been in decline, but so has the dehumanizing and demonizing mindset in individual people. This claim may seem incredible to the many intellectuals who insist that the United States is racist to the bone. But as we have seen throughout this book, for every moral advance in human history there have been social commentators who insist that we’ve never had it so bad. In 1968 the political scientist Andrew Hacker predicted that African Americans would soon rise up and engage in “dynamiting of bridges and water mains, firing of buildings, assassination of public officials and private luminaries. And of course there will be occasional rampages.”

23

Undeterred by the dearth of dynamitings and the rarity of rampages, he followed up in 1992 with

Two Nations: Black and White, Separate, Hostile, Unequal

, whose message was “A huge racial chasm remains, and there are few signs that the coming century will see it closed.”

24

Though the 1990s were a decade in which Oprah Winfrey, Michael Jordan, and Colin Powell were repeatedly named in polls as among the most admired Americans, gloomy assessments on race relations dominated literary life. The legal scholar Derrick Bell, for example, wrote in a 1992 book subtitled

The Permanence of Racism

that “racism is an integral, permanent, and indestructible component of this society.”

25

23

Undeterred by the dearth of dynamitings and the rarity of rampages, he followed up in 1992 with

Two Nations: Black and White, Separate, Hostile, Unequal

, whose message was “A huge racial chasm remains, and there are few signs that the coming century will see it closed.”

24

Though the 1990s were a decade in which Oprah Winfrey, Michael Jordan, and Colin Powell were repeatedly named in polls as among the most admired Americans, gloomy assessments on race relations dominated literary life. The legal scholar Derrick Bell, for example, wrote in a 1992 book subtitled

The Permanence of Racism

that “racism is an integral, permanent, and indestructible component of this society.”

25

Other books

Summer of My German Soldier by Bette Greene

A Cruel Season for Dying by Harker Moore

Honestly: My Life and Stryper Revealed by Michael Sweet, Dave Rose, Doug Van Pelt

Blind Trust by Jody Klaire

Fearless (Broken Love Book 5) by B.B. Reid

The Rescued Puppy by Holly Webb

Chasing Icarus by Gavin Mortimer

Istanbul Was a Fairy Tale by Levi, Mario

Goldest and the Kingdom of Thorns by Joanne Durda

Too Bright to Hear Too Loud to See by Garey, Juliann