The History of the Medieval World: From the Conversion of Constantine to the First Crusade (55 page)

Authors: Susan Wise Bauer

In the far northern lands, a new empire arose. The northern Khitan warchief Abaoji made an alliance with the Shatuo and began a series of conquests that would eventually create an enormous Khitan realm. With the death of the last Tang emperor, the inside of China had disappeared and only the outside remained.

14

A

S THE

FANZHEN

DIVIDED

China among themselves, the castle lords of Unified Silla were carving lines into their own homeland, and the cracks were deepening to the point of fracture.

The king Gyeongmun, who had sent his son to study in Tang China before its fall, had unwittingly driven a wedge into the fissures. He had married a well-born noblewoman, but she had not borne him an heir, so he had married her sister as well. The second bride was equally barren. While the two royal sisters existed in unhappy tension at the palace, one of King Gyeongmun’s concubines bore him a son and heir.

The two queens, resentful and afraid, arranged for the concubine and her baby to be murdered. But as her mistress was dying, the child’s wet-nurse snatched her charge away from the assassins and fled with him, finally taking refuge at a monastery. The little boy, Kungye, grew up there, nurtured by the monks and aware of his royal heritage. He could never forget the murder of his mother and his own displacement; he had lost an eye in the assassination attempt.

15

Some years later, another of the king’s concubines gave birth to a second son. Gyeongmun protected this child, named him crown prince, and dispatched him to China to learn the principles of Confucian government. Returning to his homeland, the boy became King Heonggang after his father’s death. He must have discovered the truth about the older half-brother exiled in a monastery; we know nothing about his reaction.

During the eleven years of his reign, Heonggang did his best to pretend that all was well, in part by spending money like water and burnishing the capital city to a high gloss. Every house had a tile roof; every fireplace burned charcoal, rather than cheaper firewood, so that the skies remained clear of woodsmoke. Meanwhile, a hundred miles out from Kyongju, the countryside seethed with thieves and bandits, private armies and ambitious warlords.

16

Most of Heonggang’s courtiers seem to have encouraged his delusion that all was well with his country, but the poet and scholar Ch’oe Chi’won was an exception. The son of a Sillan aristocrat, Ch’oe Chi’won had also spent his school years in Tang China. Unlike Heonggang, he had actually absorbed the principles of Confucian government; the

Samguk sagi

tells us that he passed the civil service exam in China on his first try and was appointed “Chief of Personnel” for a Tang province. But as his adopted country began to spin into chaos, Ch’oe Chi’won returned home.

17

In 885, Ch’oe Chi’won applied for a post in Heonggang’s government. He wanted to reform Silla before it too collapsed, but Heonggang and his hangers-on weren’t enthusiastic. “Upon returning to Korea,” the

Samguk sagi

says, “[Ch’oe Chi’won] wished to realize his ideas, but these were decadent times, and, an object of suspicion and envy, he was not accepted.”

18

The following year, King Heonggang died without an heir. First his brother and then his sister Jinseong inherited the throne and its problems; Jinseong ruled for ten years, from 887 to 897, while Silla crumpled around her.

Queen Jinseong comes off badly in the contemporary accounts; she was “of manly build,” one chronicle tells us, and then reverses itself and accuses her of bringing “pretty young men” to court and installing them in paper positions. To be female and on the throne during the collapse of a medieval kingdom generally elicited accusations of lust, corruption, and general viciousness: the queen’s sex life becomes a convenient explanation for the end of an era. But the real culprits in Silla’s ongoing crisis were the castle lords, who continued to shake down the peasants and farmers who lived under their power, building luxurious lives on the backs of Silla’s laborers.

19

Queen Jinseong tried to keep her government funded by cracking down on taxpayers. Taxes from rural areas hadn’t reached the capital for years, so she ordered armed men to perform a forced tax collection. This was a desperate and short-sighted solution. The farmers and craftsmen had been paying tax all along; the payments had just gone into the coffers of their local castle lords. Now they were paying double taxes. Poverty and desperation drove more men into careers as bandits (“grass brigands,” the contemporary chronicles call them), and before long the bandits were organizing themselves into small and powerful anti-government armies under capable rebel leaders. The lands just below Kyongju were dominated by the Red Trousered Bandits; a farmer turned soldier named Kyonhwon led a rebel army in the southwest; and a robber leader named Yanggil organized the resistance to the northeast. His second-in-command was none other than Kungye, the one-eyed prince, now grown and hoping to reclaim some of the power that could have been his.

20

For the moment, though, the farmer Kyonhwon had emerged as the strongest of the rebel leaders. In 892, Queen Jinseong tried to stave him off by giving him a title; she awarded him the rule of the lands south of the capital, along with the honorary appellation “Duke of the Southwest.” With this semi-official authority behind him, Kyonhwon negotiated an agreement with Yanggil and his right-hand man Kungye: he would rule in the southwest, and they would govern an area farther to the north.

Over the next few years, Kyonhwon firmed up his hold on the southwest lands while the one-eyed prince Kungye built his power to the north. In name, Kungye remained second-in-command to the bandit leader Yanggil. In reality, he was collecting personal support for himself, sleeping on the ground with his men, dividing his spoils evenly with them, and suffering their hardships.

21

Meanwhile, Queen Jinseong remained on her throne, but she was rapidly becoming a monarch in name only. Once again, the Confucian scholar-poet Ch’oe Chi’won tried to help out, this time by submitting a ten-point proposal for reform that would, in his estimation, have begun to lift the remains of the Sillan kingdom out of its current mudhole. Once again, his reforms were rejected by the Sillan court.

Ch’oe Chi’won left the doomed palace and retreated to a distant mountain monastery, where he devoted himself instead to the pursuits of the spirit and the composition of mournful lyrics in Chinese.

The frenzied rush through the rocks roars at the peaks,

and drowns out the human voices close by.

Because I always fear disputes between right and wrong

I have arranged the waters to cage in these mountains.

22

Back at court, Queen Jinseong was forced to give up her throne. The courtiers brought forward a boy whom they claimed to be yet another son of Heonggang, this one the child of a girl from an outlying village where the king had spent the night during a hunting trip. In 897, Queen Jinseong abdicated in his favor, and the fourteen-year-old boy became King Hyogong.

Kungye, the one-eyed prince, is said to have responded to the exaltation of his supposed half-brother by finding his portrait and slashing it to bits with his sword. His own ambitions were becoming clearer; later that same year, Kungye murdered his chief Yanggil and made himself leader of the rebels in the north.

23

By 900, the Duke of the Southwest, the ex-farmer Kyonhwon, felt secure enough to proclaim himself king. Kyonhwon had actually been born in the old territory of ancient Silla, but the land where he was most powerful had once belonged to old Baekje, so he named his new state Later Baekje. The following year, Kungye followed suit. He too was a native Sillan, but he centered his new state at Kaesong, in the old lands of Goguryeo, and named his kingdom Later Goguryeo.

The days of Unified Silla had ended. Once again, three nations occupied the peninsula. All peace had ended; Ch’oe Chi’won lamented that the bodies of those who had starved to death or fallen in action were “scattered about the plain like stars.” The observation is repeated by Wang Kon, a competent naval officer who fought in the forces of Kungye: “People scattered in all directions,” he wrote, “leaving skeletons exposed on the ground.” The period of the Later Three Kingdoms had begun with war and famine.

24

The one-eyed Kungye, driven by anger as well as ambition, intended to completely destroy the remnants of Silla; he spent the first years as king of Later Goguryeo pushing deeper and deeper into Sillan territory, while the young Sillan king Hyogong took refuge from a hopeless future in alcohol. Slowly, Kungye’s resentment and fury unbalanced his mind. When he was not fighting, he was parading through his new kingdom on a white horse, clad in a purple robe and a gold crown, with a choir of two hundred monks following behind to sing his praises. He grew paranoid, ordering first his wife and then both of his sons put to death for treachery. “Kungye,” wrote his general Wang Kon, “became tyrannical and cruel. He considered treacherous means to be the best, and intimidation and insults to be necessary devices. Frequent corvée labor and heavy taxes exhausted the people, forcing them to abandon the land. Yet the palace was grand and imposing, and he ignored the established conventions.”

25

Wang Kon is hardly an objective observer. By 918, Kungye had become so unbearably tyrannical that his own officers murdered him and elevated Wang Kon to the kingship instead. Kungye had claimed ties both to the royal house of the present and to the old Goguryeon kingdom of the past, but his rule was supported by military might, not by aristocratic lineage. He had claimed his crown by conquest, not by right of blood, and in doing so set himself up to die by the same sword with which he had lived.

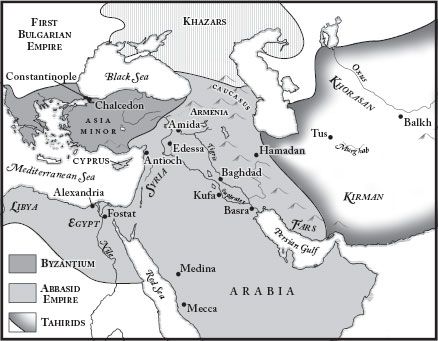

Between 809 and 833, the Abbasid caliphate is challenged by the independent Tahirids to the east

I

N

809,

THE RIGHTEOUS CALIPH

Harun al-Rashid was on his way to Khorasan with an army. The people of the province were making rebellious noises, and al-Rashid had decided to tend to the matter in person. But he grew ill on the journey and was forced to halt at the little town of Tus, where he died. He left a fortune behind. “It has been said,” al-Tabari writes, “that there were nine hundred million odd dirhams in the state treasury,” which, if true, means that al-Rashid died with three thousand tons of silver in his possession.

1

Al-Rashid had wavered over the choice of an heir. His oldest son, al-Amin, was the obvious choice, but he was also fond of his slightly younger son al-Mamun, the son of a concubine, and he thought that al-Mamun had a greater talent for governing. In the end, he made a strange, almost Frankish arrangement. He decreed that while al-Amin would succeed him as caliph, al-Mamun would become governor of Khorasan and his brother’s heir.

2

As al-Amin had children of his own, this was not to his liking. He insisted that al-Mamun come to Baghdad and recognize al-Amin’s oldest son as the heir. But for two years, al-Mamun refused to come. If he left Khorasan, the chances were that he would never return. At the same time, he stopped sending any reports to Baghdad and removed al-Amin’s name from its place in the official mottoes embroidered on the robes of state used at Khorasan—all acts that declared his independence.

3

Al-Amin retaliated by ordering that no one was to pray for al-Mamun any more during the Friday sermons. When al-Mamun received word of this, he realized that his brother was preparing to depose him as governor of Khorasan. He began to prepare for war, and al-Amin did the same. In the early days of 811, the armies of the two brothers met in battle. The army of al-Mamun, although smaller, outfought and defeated the caliph’s forces. Al-Mamun’s victory was in no small part due to the brilliant leadership of his chief general, a man named Tahir.

4

55.1: The Tahirids

Once hostilities were in the open, fighting went on, and for over a year the Abbasid empire was divided by civil war. Al-Mamun’s rebel army captured Hamadan, Basra, and Kufa; Mecca and Medina both declared themselves against the Abbasid caliph and placed their loyalty with al-Mamun instead. In a little over a year, al-Mamun had arrived at Baghdad—not as a loyal subject and brother, but as an invading conqueror.

Al-Amin and his men barricaded the city’s gates, and for another year the siege dragged on. The walls, pounded by siege engines, began to crumble. Merchants sailing into the city were forced to duck a fusillade of rocks hurled by al-Mamun’s catapults. The surrounding villages were forced to surrender; those that refused were burned to the ground. Inside Baghdad, the people grew desperate, hungry, and lawless. On the outside, al-Mamun’s general, Tahir, promised that anyone who left the city and came over to the attackers’ side would be treated well and given gifts.

At the end of the summer of 813, the defenders finally gave up. Tahir led his master’s army into the city. In the fighting and chaos that followed, al-Amin tried to swim across the Tigris to safety. A band of soldiers captured him, beheaded him, and brought the head to Tahir, who presented it to his master. Al-Mamun, who had conveniently not been in on the decision to execute his brother, prostrated himself in grief; but this did not prevent al-Amin’s head from being stuck up on the city walls—the fate of usurpers and rebels, not of duly appointed caliphs.

5

Al-Mamun was proclaimed rightful caliph, and by September most of the empire had dutifully agreed to obey him. But the authority he had seized by force never sat easily in his hands. He was forced to put down a serious rebellion in 815, and another in 817 led by his own uncle. Troubles down in Egypt, where the people were unhappy with their tax burden and their governor, were continuous. He was losing his grip on the east: he had given the governorship of Khorasan over to his general Tahir, out of gratitude for the man’s service, and Tahir had begun to pay less and less attention to commands from his caliph. One Friday evening, Tahir did not pray for the caliph during his Friday sermon—a clear declaration of his own independence.

6

Al-Mamun’s intelligence agents in Khorasan immediately sent word of this defiance to Baghdad, but on that same night Tahir died. A certain amount of confusion surrounded his death. One of his younger sons claimed that he died of a sudden high fever that struck him while he slept. An official reported that he was actually talking to Tahir when the governor’s face convulsed and he fell down in the middle of a speech. However it happened, his death seemed like good news to al-Mamun, who clapped his hands when news of Tahir’s end reached him, right after the report of his old friend’s defiance. “Praise be to God,” he announced, “who has sent Tahir on to the next life and kept us back.”

7

His celebration was premature; Tahir’s oldest son Talhah picked up his father’s defiance and declared himself ruler of Khorasan. A new dynasty had joined the already divided Muslim empire: the Tahirids, who would rule in the east, paying empty respect to the authority of the caliph but acting in independence.

Al-Mamun had won his position by conquest, and he held on to it for his entire life; he ruled as caliph until his death from typhoid in 833 and was succeeded by the heir he had designated, his half-brother al-Mutasim. But Talhah also passed on

his

authority to his brother, and the Tahirids grew in power in the east, just as the Umayyads had in al-Andalus. Now, three Islamic dynasties ruled in the once-unified Muslim lands, and the fractures would continue to spread.