The History of the Medieval World: From the Conversion of Constantine to the First Crusade (75 page)

Authors: Susan Wise Bauer

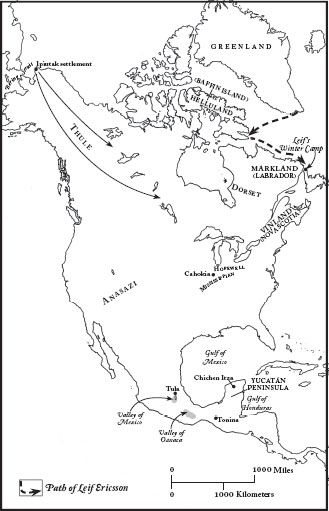

Between 985 and 1050, Leif Ericsson leads an expedition to North America, the biggest Mayan cities collapse, and the Toltecs leave paradise on earth

F

AR TO THE WEST

, the tiny Norse colony of Greenland was preparing to send colonists of its own to an unknown land.

Eric the Red’s son, Leif Ericsson, had long wanted to follow up on a fifteen-year-old rumor: that there were rich hospitable lands farther west. In 985, the Norse merchant Bjarni Herjolfsson had arrived home to discover that his parents had emigrated to Greenland while he was off trading, so he left his homeland to go and visit them. He had never sailed the Greenland sea before. When fog and north winds descended on his ship he was unable to find his way. “For many days,” says the thirteenth-century

Saga of the Greenlanders

, “they did not know where they were sailing.” When the sun finally came out, they found themselves off an unfamiliar forested coast. Bjarni’s crew wanted to go ashore, but their captain refused; instead he set course back to the east and finally sighted the coast of Greenland. When he told the settlers there of his journey, the saga adds, “many people thought him short on curiosity, since he had nothing to tell of these lands.”

1

Leif Ericsson had no shortage of curiosity. He bought Bjarni’s ship, stocked it, and in 1003 convinced Eric the Red, now in his fifties, to head up one more expedition to the west. The legendary explorer was reluctant to leave his home (“he was getting on in years,” the saga says, “and not as good at bearing the cold and wet as before”) but unable to turn down the challenge.

As the father and son rode towards the harbor where their ship lay anchored, Eric’s horse stumbled and threw him, injuring his foot. Eric took this as a bad omen and went back home, leaving his son in command.

Leif and his men sailed northwest until they reached the southern end of Baffin Island, and then down along the coasts of the North American islands and peninsulas. He named the lands as he passed them: inhospitable Baffin Island earned the name “Helluland,” or “Stone-slab land” forest-covered Labrador became “Markland,” or “Forest land” Nova Scotia was named “Vinland,” or “Wineland,” since the explorers found grapes there and immediately put them to use.

2

Leif decreed that the crew would build a winter camp on this new found land and remain there through the cold months.

*

But these were less severe than he expected. The unusual warmth of the Medieval Climatic Anomaly still blanketed the northern lands: “There was no lack of salmon both in the lake and in the river,” the

Saga of the Greenlanders

tells us, “and this salmon was larger than they had ever seen before. It seemed to them the land was so good that livestock would need no fodder during the winter. The temperature never dropped below freezing, and the grass only withered very slightly.” When spring came, Leif returned home with a ship filled with virgin timber, grapes, and wine. Eric the Red was able to see the long-delayed fruit of that original journey west just before his death in 1004.

3

The shores of the new country, apparently unclaimed, seemed like the ideal place for a permanent colony, and the following year Leif’s brother Thorvald launched an expedition to find the perfect settlement spot. He and his men settled in at Leif’s winter camp and began to mark out the borders of farms and claims. For over a year, they saw no “signs of men or animals” except for a single wooden grain cover, left on a small island by unknown inhabitants.

Then, during the second summer, they spotted inhabitants: nine men and three hide-covered boats drawn up in a sheltered cove. It doesn’t seem to have occured to the Norsemen to make any sort of peaceful approach; they went directly into conquest mode. “They managed to capture all of them except one, who escaped with their boat,” says the

Saga of the Greenlanders

, “[and] killed the other eight.”

This brought an immediate counterattack. That same night, a “vast number” of hide-covered boats swept down the nearest inlet, with the inhabitants raining arrows upon the Norsemen, and then almost as quickly whisked themselves away. The retaliatory raid left the Norsemen unhurt—except for Thorvald, who had been fatally struck by an arrow in the armpit. His men buried him on the farm site he had chosen for himself and went back home.

4

Three years later, a wealthy and experienced Norse explorer named Thorfinn Karlsefni arrived on Greenland’s shores from the homeland. Within weeks he had professed his love for Leif Ericsson’s sister Gudrid; when Leif (now head of the family) gave permission, Thorfinn married her.

75.1: The Hopewell Serpent Mound from the air, surrounded by modern pathways

Credit: Ohio Historical Society

That same spring, the couple decided to make another expedition to the west. Thorfinn hired a crew of sixty men—along with five women and plenty of livestock. This time, the Norsemen intended to stay in the new land if they could.

They arrived in Vinland without difficulty and began to build a settlement. The new land was just as fertile as previous expeditioners had told them, and their timber homes were soon stocked with grapes, fish, game, and (thanks to a chance beaching) whale meat. Less than a year after their arrival, Gudrid “gave birth to a boy, who was named Snorri”—the first European baby born in North America.

5

But the natives of their new homeland were now on the alert, and the settlers were soon building palisades and arming themselves for battle. Skirmishes broke out, and there was at least one large-scale fight with fatalities. The

Saga of the Greenlanders

gives few other details, but the attacks must have been seriously worrying, because the following year Thorfinn “declared that he wished to remain no longer, and wanted to return to Greenland.” Another saga adds that the natives had catapults and were well armed, and attacked while “shrieking loudly.” For this reason the Greenlanders called them

Skraelings

, the “Shriekers.”

6

The Norse sagas give us a rare glimpse into the world of people who have left only physical remains behind—in the words of anthropologist Alice Beck Kehoe, a “history without documents.” The Greenlander settlement sat on the northeastern corner of the North American continent, a land mass that was probably populated millennia earlier, when the Bering Strait was still a land bridge connecting North America with Asia. Some of the travellers who came into the northern reaches settled on the icy shores. One town, just east of the strait, was built at least five hundred years before the Greenlanders arrived on the opposite coast, over three thousand miles away. Archaeologists have given its culture the name “Ipiutak” the Ipiutak settlement boasted more than six hundred houses and a huge cemetery, and the remains of the town are scattered with elaborate ivory carvings, knife handles, and harpoons.

7

By

AD

1000, another culture had grown up from the Ipiutak ruins, and was rapidly spreading eastward to the coast; archaeologists call the people of this culture the “Thule,” distinguished from their ancestors by their use of iron tools instead of stone. The Thule managed to displace the culture that had already grown up on the northeastern American coast: the Dorset, a seal-hunting people who gave way, in the face of the invaders, and scattered into oblivion. The Skraelings who fought against Thorfinn’s men were either Dorset or Thule, possibly bands of both.

8

We know what these tribes built, what weapons they used, what animals they hunted, and roughly how they lived; we know nothing of their stories, their histories, or their ambitions. The same is true of the tribes farther south. By Leif Ericsson’s day, the Hopewell culture had spread across what is now Ohio and Illinois, reached its height, and dwindled away. The Hopewell builders left behind enormous tomb mounds, each a geometric set of circles and squares, and a winding mysterious earthwork, five feet tall and over a thousand feet long, in the shape of a serpent devouring an egg.

In their place, and slightly more to the south, the Mississippian peoples built cities. The largest of these was Cahokia, spreading across almost five square miles, with perhaps thirty thousand people living in it. They have left behind them tremendous earthen mounds, the remains of foundations and well-planned streets, tools and figurines, burial grounds and sacrificial pits—one containing fifty young women, all apparently executed at the same time to accompany a great nobleman into death.

9

Farther west, the Anasazi people built complexes from adobe bricks of baked clay and sand: rows of linked dwellings, some with as many as seven hundred rooms, housing thousands. The Anasazi were hunters, farmers, and turquoise-miners; their civilization reached its height just before

AD

1100.

10

75.1: Settlements of the Americas

The history of these North Americans, and the dozens of smaller tribes and states that spread across the continent, remains unknown. Archaeologists have pieced fragments together into kaleidoscopes that give us glimpses of daily life, but the large story of each civilization has been lost to the historian’s view. Cahokia was as large as the Mesoamerican city of Teotihuacan, as populous as the Zapotec city of Monte Alban; its rulers were as powerful as the Mayan sovereigns. But without written history we know nothing of the names of their kings and queens, the nature of their gods and goddesses, the struggles of their noblemen and peasants.

*

F

AR TO THE SOUTH

, the Mayan and Zapotec chronicles emerged from the long silence of drought, famine, and disorder. Bits and pieces of those chronicles have come down to us through translations made by Spanish conquerors, centuries later. Broken apart and distorted by their interpreters, they provide us names of kings and queens and a few cryptic details: a tiny, fogged peephole into the distant Mesoamerican past.

†

Put together, the chronicles and the ruins of cities tell us that the Maya never regained their former grip on the land bridge between the continents. The southern cities began to collapse, brought down in part by their own prosperity; a population boom filled the streets, the surrounding fields, and the more distant villages with hungry mouths. Mayan farmers were forced to make use of every single bit of fertile land. Swamps were converted to gardens, flood plains were cultivated, forested areas slashed and burned to create new fields. Food production kept up with demand, but just barely. There was no extra grain left at the end of the growing season.

11

This was fine as long as the weather remained good, but when drought hit in the middle of the ninth century, the Maya began to starve. Excavations in Mayan cemeteries show the slow but escalating signs of malnutrition. Adult skeletons grow shorter and shorter, signs of scurvy and anemia abound, striations in the teeth of young children testify to long periods of fasting.

12

The aristocracy tried to cope by seizing food for themselves, but in the end both aristocrats and commoners were forced to leave the overcrowded cities in search of fresh lands. Buildings were left half-finished as the population of the great urban centers drained away. The last Mayan monument in the south was erected on January 15, 909, in the city of Tonina, which sat on a ridge south of the Gulf of Mexico. After that, silence. The Maya who were still strong enough to travel moved elsewhere. Some journeyed far to the southeast and settled on the high ground south of the Gulf of Honduras. Others went north; excavations show a sudden surge in northern population as the refugees arrived, along with newly terraced hill-fields, necessary to feed the newcomers.

13