The Reluctant Film Art of Woody Allen (6 page)

Read The Reluctant Film Art of Woody Allen Online

Authors: Peter J. Bailey

Tags: #Biography & Autobiography, #Entertainment & Performing Arts, #Performing Arts, #Film & Video, #History & Criticism, #Literary Criticism, #General, #Literary Collections, #American

The brief affair generated by these kisses precipitates the usual marital and extramarital tensions, circumstances replicating the plot of an Ida Lupino film,

They Drive By Night

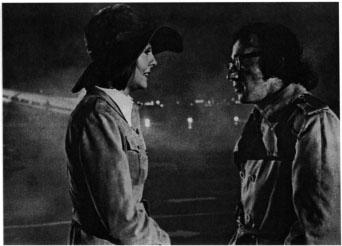

, which Linda wants to watch on the late movie. It’s “the one where she’s happily married and suddenly becomes involved with her husband’s best friend,” Linda explains. In a film so centrally concerned with the intercession of film narratives within our emotional lives, it is only appropriate that Felix’s anxieties about informing Dick of the affair get configured as movie scenes: Felix and Dick become stuffy Brits amicably resolving their romantic conflict without ever removing their pipes from their mouths; then Felix imaginatively transforms them into characters in a Vittorio deSica movie in which bakery workers Felix and Dick scream at each other through thick Italian accents. All of this is preparing for the climactic airport scene in which Felix will have the opportunity to play out Rick’s romantic love-renunciation scene, delivering a speech which, he forthrightly admits, is “from

Casablanca

. I’ve waited my whole life to say it.”

“That’s beautiful,” is Linda’s response to Felix’s thoroughly practiced “you’ll regret it—maybe not today, maybe not tomorrow” recitation, insisting that “the most wonderful thing in the world has happened” because Felix seduced her without leaving “open books lying around” and he didn’t have to “put on the proper mood music.” In effect, he had “scored” without resorting to all the self-conscious stratagems he used previously in his hapless attempts to “make an impression” on women. He had managed; Linda is suggesting, overcoming his film inspired self-consciousness and act forthrightly upon his desire. Bogart adds his own commendation of Felix’s closing monologue: “That was great,” Bogart tells him after Linda and Dick have deplaned for Cleveland, “you’ve really developed yourself a little style.”

“I do have a certain amount of style, don’t I?” Felix responds in wonderment. This realization achieved Felix’s phantasmagoric model of unself-conscious masculine artlessness has become dispensable. Accordingly, Bogart tells him, “Well, I guess you won’t be needing me anymore,” paying his protégé the ultimate male compliment by acknowledging, “There’s nothing I can tell you now that you don’t already know.” Significantly, Bogart never mentions that it’s Linda, not Felix, who renounces their affair in order to return to her marriage by flying off to Cleveland with Dick. This deviation from the

Casablanca

paradigm notwithstanding, Felix is clearly poised on the very brink of epiphany, one that builds upon his admission that he has “a certain amount of style.” “The secret’s not being you,” he boasts at last, “it’s being me. What the hell—I’m short enough and ugly enough to succeed on my own.”

Untold thousands of moviegoers have been charmed by Felix’s self-liberating declaration and by the salute Bogart offers him in response to it: reprising the affectionate appellation he has used with Felix throughout the film, Bogart smiles broadly at him, saying “Here’s looking at you, kid.” It’s a lovely moment of closure, the echo of Rick’s final words to Ilsa seeming to translate that scene’s sad farewell into

Play It Again, Sam’s

affirmation of Felix’s achievement of freedom from Bogart’s oppressive influence. It’s evident that what we are watching is the end of a beautiful split-protagonist friendship. But then, “Here’s looking at you, kid,” was the toast Rick and Ilsa shared in avowal of their love, a sentimental formula for the idea that “we’ll always have Paris.” Rick never says their obsession with each other will cease simply because “the problems of two little people don’t amount to a hill of beans in a crazy world like this”; if the most famous scene in American movie history works, the film’s dramatic evocation of the emotional cost of that renunciation is the reason. Rather than merely being a shorthand goodbye, Rick’s “Here’s looking at you, kid,“ is a way of recalling Paris, of asserting that memory’s potency, and of affirming that Rick and Ilsa’s separation will be geographical, not emotional or spiritual.

When Bogart salutes Felix with the same expression, he is implicitly commending him for so impressively reenacting the role which Bogart initiated, acknowledging the psychic progress that Felix’s playing out of the climactic scene constitutes, and perhaps saying as well that Felix too “will always have Paris”—that he hasn’t completely escaped the mental thrall in which he’sheld by Hollywood-inspired romance, by Bogart’s bravura masculinity, by the movies. In other words, Felix’s mind may be forswearing its dependency upon the romantic ethos of

Casablanca

but his heart is wailing, “I don’t want to go! I don’t want to go!” The “little style” Felix has developed is utterly mediated by

Casablanca,

and despite his putative declaration of independence from Bogart and from the desire to reenact the

Casablanca

plot, the only way he has contrived to assert his independence from that narrative has been through plagiarizing it. As Douglas Brode pointed out in discussing the “South American Way” scene in

Radio Days,

“As the men in Joe’s family slip into the moodby lip-synching the male chorus’s song lines, they too briefly turn their lives into art. ‘The desire to do that—to become one, if only for a second, with either popular or classic art—has been at the root of Allen’s characters since his very first film.”

7

As Felix confidently walks off across the airport tarmac, alone, embraced by his newly discovered insularity and self-reliance, the soundtrack undercuts the ending’s determinacy and sense of felicitous closure: Sam is playing it again—playing “As Time Goes By,” the song which Rick forbade him to perform at Rick’s Place in

Casablanca

because it was too potent a reminder of Ilsa and Paris. The “fundamental things apply as time goes by,” Dooley Wilson croons as Felix vanishes into airport fog, and we know that those fundamental things include the fact that “when two lovers woo, they still say ‘I love you.’”

Play It Again, Sam

is the first of many Allen films which consistently and deliberately merges the “fundamental things” of human romance with their idealized representations on movie screens, the film depicting simultaneously Allan Felix’s self-liberation from the

Casablanca

mythos and his continuing obsession with it.

In

The Purple Rose of Cairo,

a Hollywood actor offers Cecilia a sentiment invoking the same basic paradox depicted in

Play It Again, Sam’s

ending: “Look, I-I love you. I know that o-only happens in movies, but … I do.” When D.J. of

Everyone Says I Love You

explains how the film of her family’s crazy year evolved, she recalls her half-sister, Skylar, suggesting that it must be “a musical or no one will believe it”; as a result, the characters constantly and highly self-consciously burst into song to express the status of their current relationship to Eros. Allen’s translation of the old bromide that people might never have fallen in love if they’d never heard it talked about would be that few people would fall in love were they not acting out the plots of movies or the lyrics of popular songs. There

are

Woody Allen films in which human love is affirmed as real and redemptive—

Midsummer Night’s Sex Comedy, Hannah and Her Sisters, Manhattan Murder Mystery

, and

Mighty Aphrodite

can all be construed in these terms—but his most substantial films more typically depict the human erotic tropism as being irremediably inbred with media-inspired illusions; the “same old story, the fight for love and glory” often gets configured somewhat jadedly as just “the same old story” recycled endlessly through movie vehicles like

Casablanca

.

Lee Guthrie’s 1978 biography quotes Allen’s characterization of the original theatrical version of

Play It Again, Sam,

which opened on Broadway in 1969. It’s “an autobiographical story about a highly neurotic lover, an accumulation of themes which interest me: sex, adultery, extreme neuroses in romance, insecurity. It’s strictly a comedy. There’s nothing remotely noncomicabout it. “

8

The equivocation perceivable here between Allen’s acknowledgment of the autobiographical nature of the play with its dramatic themes and his insistence upon its “strictly comic” character is typical of Allen’s assessment of his early work, though the tendency to minimize the serious ambitions of his films, as we’ll see, continues down through his comments on

Deconstructing Harry

. Julian Fox cites the comments of Allen friends of the period who located the inspiration for the play in Allen’s recent divorce from Louise Lasser, the plot exploiting his friends’ not-always-felicitous attempts to fix him up with dates; additionally, Fox registers those Allen associates’ view that

Play It Again, Sam

represented the first time that Allen’s dramatic work had “engineered a more than passing connection between his on-screen and off-screen identities.” Allen’s disclaimers notwithstanding, Fox argues, “the one autobiographical element which he could never be able to deny is the way he has exploited his lifelong addiction to cinema.”

9

Many of the parodies of

film noir

scenes which proliferate in the movie are absent from the theatrical version, but Allen’s satirical piece about his recently-opened play in

Life Magazine

gave readers an introduction to the Bogart-fixation those parodies would amplify cinematically in the movie. Allen—who seems as intent upon blurring the distinction between himself and Allan Felix in the article as he was in eliminating the distinction between himself and his comic persona in his standup act—claims to have fallen in love with a woman named Lou Ann Monad, who breaks his heart by leaving him for the drummer of a rock group called Concluding Scientific Postscript. “Clearly,” Allen contends,

it was time to fall back on the unassailable strength and wisdom of Humphrey Bogart. I curled my lip and told her that she was a dame and weak and quoted a passage of hard-liner Bogey from

Key Largo

. When that didn’t work, I resorted to an emotional plea culled from the high points of

Casablanca

. Then I tried something from

The Big Sleep

and then

Sahara

… When it still left her unmoved, I fell back on

The Petrified Forest

and then

Sabrina

. Panicky now, I switched to a grubby Fred C. Dobbs in

The Treasure of the Sierra Madre

and asserted myself with the same petty ego he used on

Tim

Holt, to no avail. She laughed derisively, and moments later I found myself clicking two steel balls together and begging her not to leave me as I muttered something about the strawberries. I was given the gate.

10

Arguably, “[t]here’s nothing remotely no comic about” this classic bit of Woody Allen

shtick

—nothing, that is, except the understanding of human insecurity required to imagine a character so lacking in self as to so desperately seek to fill the gap with this succession of Humphrey Bogart movies. Allen would, of course, suggest a decade later that there is nothing no comic about Leonard Zelig, either.

“Apart from its commercial success,

[Play It Again, Sam]

also offered Woody a brand new perspective and maturity for his future career,” Fox contended; “starting with

Sam,

a popular image of [Allen] had begun to appear which, for movie audiences at least, was taken to be both a reflection of themselves and all the things they assumed that Woody was about.”

11

Fox is right about this and it is also true that it’s impossible to completely separate Allan Felix’s self-affirmation that “I’m short and ugly enough to succeed on my own” from Woody Allen’s own gradual, hard-won transformation of himself from reluctant stand-up comedian to playwright and lead Broadway actor of

Play It Again, Sam,

to screenwriter, lead actor, and director of

Sleeper, Love and Death, Annie Hall,

and so on. By the time he had completed the play script of

Play It Again, Sam,

it was clearly obvious to Allen that, given all the project ideas he had to shelve to appear in the Broadway play,

12

“I guess I do have little style, don’t I?” The film version—facilitated by the remarkably unobtrusive directorial efforts of Herbert Ross—allowed Allen/Allan Felix the perfect personal apotheosis of making that declaration in the medium in which the “little style” he’d discovered in himself would express itself most emphatically over the ensuing three decades.

Play It Again, Sam

is undeniably a watershed work in Allen’s career, one which obliquely celebrates his transcendence of the intimidations of the cinematic models whose grandeur inspired and inhibited his own creativity much as Bogart inhibits/inspires Felix’s efforts with women. However, as the Bergman-haunted, Fellini-inflected films that followed

Play It Again, Sam

suggest, that transcendence was tentative and partial; Woody Allen, filmmaker, is still subject to bouts of the extreme anxiety of influence, vulnerable to acquiescing to the strategy of “when in creative doubt, invoke the masters,” This characteristic is less a failing than Allen’s acknowledgment of the sometimes dominating affect of other filmmakers’ visions upon his own, his way of dramatizing the idea that the existence of an unadulterated, unmediated plot is no more conceivable than a completely original, uncontinent self. However much style we generate, in other words, we’re still haunted by the distinctive styles of other films, other selves, and Woody Allen’s films are honest enough repeatedly to acknowledge that omnipresence of influence. “I said I would never leave you,” Ilsa tells Rick in the concluding scene of

Casablanca,

and his response predicts the trajectory of Allen’s film career in terms of its sustained permeation by filmic precedents and influences: “And you never will.” To understand what can be construed as a fundamental antinomy of Woody Allen’s filmmaking career, one must appreciate how completely conflictual in Allen’s mind is Rick’s most affecting reassurance to Ilsa: “We’ll

always

have Paris.”