The Rise and Fall of a Palestinian Dynasty (64 page)

Read The Rise and Fall of a Palestinian Dynasty Online

Authors: Ilan Pappe

Others – mainly the Husaynis who remained in Jerusalem – were not content to shape their image for posterity but returned to public life in the spheres of welfare and education. A notable example was Khalid al-Husayni, Abd al-Qadir’s brother who succeeded him as commander of the Palestinian forces in Jerusalem until the end of the war of 1948. Afterwards he became the director of the United Nations Relief and Works Agency (UNRWA) in the district of Nablus and made his home in that town. He was perhaps the only Husayni who worked directly with the refugees, but apparently they were not grateful. Towards the end of February 1951, he was twice attacked by an armed refugee in Nablus; the second blow was fatal. He was projected as the main culprit in the Palestinian catastrophe. The family believes that the Hashemite secret service was behind his assassination, and it has been said that the murder of King Abdullah was an act of revenge.

In the 1990s, Khalid’s work was continued by his son Sharif, who worked in Orient House. One of the few Husaynis who engaged in political activity during the 1980s, he joined the Palestinian leadership in the Occupied Territories.

The story of Ishaq Musa al-Husayni, who made a name for himself in the 1950s, is quite different. He became a known spokesman for the

Palestinian cause in the region and beyond. At first he went to Aleppo in Syria and in 1949 settled in Beirut, where he taught at the American University until 1955. Like other members of the family, he was impressed by Gamal Abd al-Nasser, and in the late 1950s he moved to Cairo and taught at the American University there. During those years he wrote one of the pioneering studies on the Muslim Brotherhood. In the 1960s, he contributed to the cause by writing books about the Arab character of Jerusalem and Palestine.

18

During the following two decades, he was regularly invited by leading universities in the West to lecture on Arabic literature. He returned to Jerusalem in 1973, almost thirty years after he had left it, and to the subject of Palestinian literature as distinct from Arab literature as a whole. He has done a good deal to strengthen higher education in East Jerusalem. He died in 1990 at the age of eighty-six.

FAYSAL AL-HUSAYNI

The best-known member of the family at the end of the twentieth century was Faysal al-Husayni, the son of Abd al-Qadir. He played a major role in the Palestinian leadership in the Occupied Territories and in the Palestinian Authority. In May 2001 he died of a heart attack while on a frustrating political mission to Kuwait in an abortive attempt to secure a reconciliation with the Kuwaiti regime in the wake of Arafat’s unequivocal support for Saddam Hussein in the First Gulf War.

Since the Palestinian Authority, to which Faysal belonged, did not enjoy the full support of the Palestinian people, and since the future of Palestinian politics remains obscure, it is not yet possible to define Faysal al-Husayni’s place in his people’s history. The climax of his political career was probably the eve of the Madrid Conference in 1991, where he was a senior member of the Palestinian delegation at the peace talks with Israel. But he lost his seniority to Mahmud Abbas, aka Abu Mazen, who succeeded Arafat in 2004 as President of the Palestinian Authority.

19

Faysal al-Husayni was born in Baghdad in 1940, when his father Abd al-Qadir was staying there with al-Hajj Amin. But soon afterwards, he moved with his family to Cairo where he spent his first twenty years until he returned to Jerusalem as a young man in 1961. He was very active as a student in Cairo, and in 1958 he founded the General Union of Palestinian Students, which became one of the pivotal institutions in the PLO.

In Jerusalem he was attracted to the Palestinian nationalism propagated by Fatah, and he worked in the organization’s office in East Jerusalem before the June 1967 war. At the age of twenty-seven, he wished to be even more active and asked to be recruited to Fatah’s fighting units. When the 1967 war broke out, he was attending a course offered by the Palestinian Liberation Army, the military organization created by the Arab League, and he returned to Jerusalem in secret.

In November 1967, he was arrested for possession of weapons, which he had received from Arafat, who commanded Fatah in the territories and was trying in vain to start a popular uprising against the Israeli occupation. Before giving the slip to the Israeli army and crossing to Jordan, Arafat held a brief meeting in Ramallah with Faysal al-Husayni. At his trial, Faysal said that he himself did not believe in the efficacy of the armed struggle and wanted to dedicate himself to the political path. This statement led the judges to sentence him to only one year in prison.

When he was released, he married his cousin Najat al-Husayni, who bore him a son and a daughter. For years he engaged in private business, then worked in his uncle’s X-ray institute in East Jerusalem, helped with the development of the lands at Ayn Siniya and in 1979 returned to public life, founding and directing an academic institute of Arab studies. He made an important contribution to the collection of archival and academic material that enabled young Palestinian historians to reconstruct the history of the country and to recreate almost from nothing the Palestinian collective memory that had been effaced by Israel since 1948. Not surprisingly, the Israeli authorities would not accept him as a purely academic figure and several times placed him in administrative detention.

When the First

Intifada

broke out, Faysal was in Abu Iyyad’s camp in Fatah, which was looking for a political way to realize the gains of the uprising. He had led the advisory team of PLO delegations at various meetings in the Arab countries that drew up a well-defined Palestinian position and consequently took part in the Palestinian delegation that went to Madrid in 1991 to discuss a comprehensive peace settlement of the Arab-Israeli conflict.

20

But there was little in Faysal al-Husayni’s modern biography to connect him to the family history. ‘The son who did not follow in his father’s footsteps’, said the Israeli journalist Pinhas Inbari, meaning that Faysal had worked to bring about Israeli-Palestinian peace, whereas his father had fought against Zionism and paid with his life. But it must

be remembered that the family had ceased to be a meaningful political body in Faysal’s life and in Palestinian politics as a whole. It was Faysal’s younger brother Ghazi who believed he was following in his father’s footsteps when he joined the Islamic Jihad movement, whose name echoes that of the organization created by Abd al-Qadir,

al-Jihad al-Muqaddas

.

21

Let us conclude this book not with Faysal al-Husayni, but with al-Hajj Amin. Towards the end of his life, al-Hajj Amin occupied himself more and more with the pan-Islamic world, since he had been deposed from all significant positions in Palestine and the pan-Arab arena had faded since 1967. He tried to participate in the first pan-Islamic conference in Rabat, Morocco, in 1969 but was prevented by the strenuous protests of the PLO, which wanted to eliminate him as a representative of Palestinian nationalism. When the second conference was held in Lahore, Pakistan, in 1974, al-Hajj Amin was invited, since by then he had become weak and his health had deteriorated. The conference took place in February, and in July of that year al-Hajj Amin died of a heart attack in the Mansuriya quarter of Beirut in Lebanon.

22

The following year, the civil war erupted in Lebanon and the former

mufti

’s house was burned down by the Maronite-Christian Phalangists. Mona Bori, today a refugee in Texas, was a neighbor and managed to photograph some of the archives in the house that burned down. Some of the missing material was seized by the Phalangists, and no one knows where it is or what was contained in the material that perished. But whatever it was, it was not likely to diminish al-Hajj Amin’s grave responsibility as head of the family for his people’s tragedy.

At al-Hajj Amin’s grave, his only son heard the leaders of the PLO praising and eulogizing his father (his six sisters did not come to the funeral). But Salih remained in Spain and did not follow the family’s political tradition. Nor did the fulsome eulogies last very long. After al-Hajj Amin’s death, the question of his place in Palestinian historiography was raised. He himself had tried as early as 1954 to engrave the ‘official’ version of his life and role into Palestinian history. In newspaper articles and anthologies, he repeatedly described his positive role in the struggle for Palestine, hoping that the catastrophe would appear as a terrible concatenation of irresistible hostile forces. At the heart of his historiographical analysis was the British betrayal. His mixing of rational thinking with demonic mythology served to diminish his historical stature rather than enhance it.

The discussion continued without him and focused on his responsibility for the Nakbah. Even before he died, Palestinian historians and intellectuals of the left severely criticized the role of the upper class, with the Husaynis at its center. ‘The urban upper class remained alien to the armed struggle throughout the period of the mandate,’ argued Hisham Sharabi. ‘This class especially benefited through that period.’ The problem of the Husaynis, Sharabi stated in 1969, was that they perceived Zionism not as the ultimate danger but as a nuisance, while to the peasants and the workers Zionism was a tangible threat.

23

During the 1980s, the discussion became clearer and more focused. The attack on al-Hajj Amin was led by the Palestinian historian Samih Shaqib, and the opposite viewpoint was presented by the historian Husni Jarar. In 1988 the two conducted a thorough debate that left the

mufti

’s historiographic image in tatters.

24

In the next decade, the picture became more balanced when Philip Mattar published the first comprehensive Palestinian biography of al-Hajj Amin, offering a balance-sheet of achievements and failures.

25

Only Abd al-Qadir al-Husayni’s reputation has remained impeccable, and perhaps it was natural that his son Faysal, rather than al-Hajj Amin’s son Salih, went on to play a part in Palestinian politics. It also redounded to the Husaynis’ credit that Yasser Arafat, the unquestioned leader of the Palestinian revolution from 1969 to 2004, was related to their family on his mother’s side. Furthermore, he always made a point of telling everyone that in 1948 he had been Abd al-Qadir’s personal secretary.

Above all, al-Hajj Amin should not be confused with his family’s pivotal role in the history of Palestine, for good or for worse. Its achievements and failures – and those of the other notable families – were those of Palestinian society as a whole. And since the Husaynis, more than any other family, were at the center of Palestinian politics on the eve of the 1948 catastrophe, they bear heavy responsibility for its occurrence. And yet, one should not for a moment forget the nature of this responsibility. It was the inability to defend and organize a community that was the object of an ethnic cleansing ideology and praxis. It is very difficult to assess whether an alternative leadership would have fared better in the face of such a calamity.

By 1948, the family had declined not only because of the Nakbah but also because the Arab-Ottoman world to which it belonged was gone for ever. In the words of the English travel writer Colin Thubron, who visited Jerusalem in the 1960s: ‘The Husaynis no longer rule over the

city’s religious life, nor do the Nashashibis rule over the municipality. A whole generation has departed from the highway followed by their ancestors for centuries.’

26

The Husaynis are not what they had been. Their history shows that they were part of a culture, an experience and a life that vanished in 1948. The desire to resurrect them lies at the heart of the historical-political thought of all Palestinians, wherever they may be. This thought animates the struggle over this country, and if it were understood by the other party in the conflict it could lead to reconciliation.

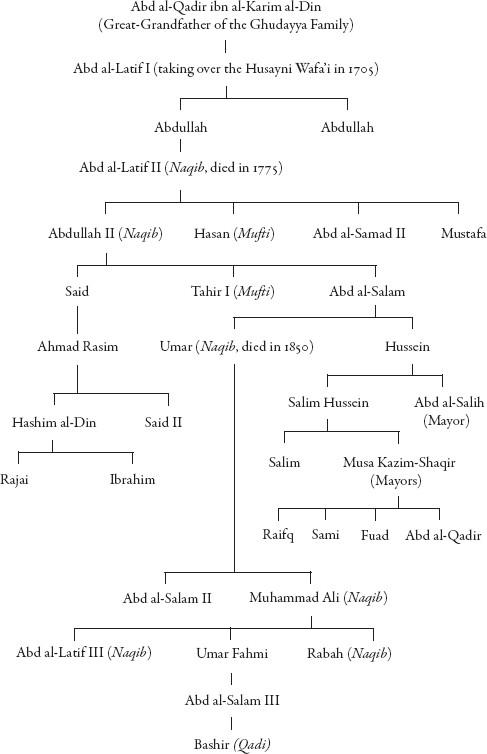

Family Trees

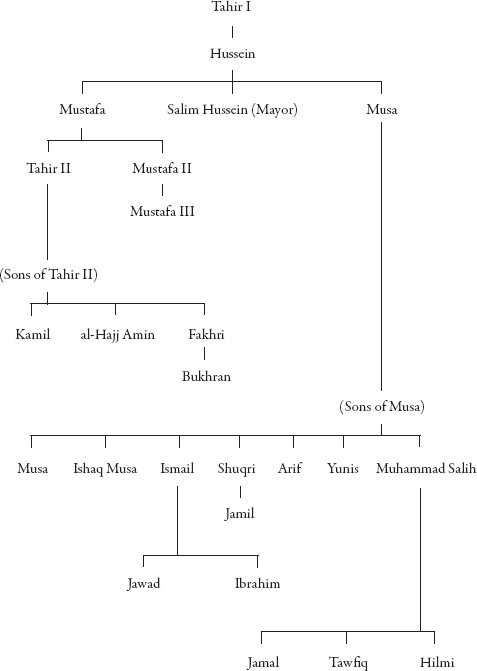

The Tahiri Branch