The Rule of Four (19 page)

That man was Francesco Colonna, and his book was hardly the pushover Paul had hoped. Though Paul flexed his mental muscle, he found that the mountain wouldn’t move. As his progress slowed, and the fall of junior year darkened into winter, Paul became irritable, quick with sharp comments and rude mannerisms he could only have learned from Taft. At Ivy, Gil told me, members began to joke about Paul when he sat alone at the dinner table, surrounded by stacks of books, talking to no one. The more I watched his confidence dwindle, the more I understood something my father had said once: the

Hypnerotomachia

is a siren, a fetching song on a distant shore, all claws and clutches in person. You court her at your risk.

And so it went. Spring came; coeds in tank tops tossed Frisbees beneath his window; squirrels and blossoms stooped the tree branches; tennis balls echoed in play; and still Paul sat in his room, alone, shade drawn, door locked, with a message on his whiteboard saying

DO NOT DISTURB

. All that I loved about the new season, he called a distraction—the smells and sounds, the sense of impatience after a long and bookish winter. I knew that I myself was becoming a distraction to him. Everything he told me started to sound like the weather report from a foreign land. I visited him little.

It took a summer alone to change him. In early September of senior year, after three months on an empty campus, he welcomed us all back and helped us move in. He was suddenly open to interruptions, eager to spend time among friends, less fixated on the past. In the opening months of that semester, he and I enjoyed a renaissance in our friendship better than anything I could’ve expected. He shrugged off the onlookers at Ivy who hung on his words, waiting for something outrageous; he spent less time with Taft and Stein; he savored meals and enjoyed walks between classes. He could even see the humor in the way garbage men emptied the Dumpster beneath our window each Tuesday morning at seven o’clock. I thought he was better. More than that: I thought he was reborn.

It was only when Paul came to me in October of senior year, late one night after our last fall midterms, that I understood the other thing our theses had in common: both of our subjects were dead things that refused to stay buried.

“Is there anything that could change your mind about working on the

Hypnerotomachia

?” Paul asked me that night—and from his tense expression, I knew he’d found something important.

“No,” I told him, half because I meant it, but half to get him to tip his hand.

“I think I made a breakthrough over the summer. But I need your help to understand it.”

“Tell me,” I said.

And however it began for my father, whatever galvanized his curiosity in the

Hypnerotomachia,

this was how it started for me. What Paul said that night gave Colonna’s long-dead book new life.

“Vincent introduced me to Steven Gelbman from Brown last year when he saw I was getting frustrated,” Paul began. “Gelbman does research with math, cryptography, and religion, all in one. He’s an expert at the mathematical analysis of the Torah. Have you heard of this stuff?”

“Sounds like kabala.”

“Exactly. You don’t just study what the scriptural words say; you study what the

numbers

say. Every letter in the Hebrew alphabet has a number assigned to it. Using the order of the letters, you can look for mathematical patterns.

“Well, I was doubtful at the beginning. Even after sitting through ten hours of lectures on the Sephirothic correspondences, I didn’t buy it. It just didn’t seem to relate to Colonna. But by the summer I’d finished the secondary sources on the

Hypnerotomachia,

and I started working on the book itself. It was impossible. I would try to force an interpretation onto it, and it would throw everything back in my face. As soon as I thought a few pages were moving in one direction, using a certain structure, making a certain point, suddenly the sentence would end, and in the next one everything would change.

“I spent five weeks just trying to understand the first labyrinth Francesco describes. I studied Vitruvius to understand the architectural terms. I looked up every ancient labyrinth I knew—the Egyptian one at the City of Crocodiles, the ones at Lemnos and Clusium and Crete, half a dozen others. Then I realized there were four different labyrinths in the

Hypnerotomachia

—one in a temple, one in the water, one in a garden, and one underground. As soon as I thought I was beginning to understand one level of complexity, it quadrupled. Poliphilo even gets lost at the beginning of the book and says,

My only recourse was to beg the pity of Cretan Ariadne, who gave the thread to Theseus to escape from the difficult labyrinth.

It’s like the book understood what it was doing to me.

“Finally I realized the only thing I knew that

definitely

worked was the acrostic with the first letter of every chapter. So I did what the book told me to do. I begged the pity of Cretan Ariadne, the one person who might be able to solve the maze.”

“You went back to Gelbman.”

He nodded. “I ate crow. I was desperate. In July, Gelbman let me stay with him in Providence after Vincent insisted I was making progress with the method. He spent the weekend showing me more sophisticated decoding techniques, and that’s when things started to pick up.”

I remember looking out the window beyond Paul’s shoulder as he spoke, sensing that the landscape was changing. We were sitting in our bedroom in Dod, alone on a Friday night; Charlie and Gil were somewhere below our feet, playing paintball in the steam tunnels with a group of friends from Ivy and the EMT squad. The following day I would have a paper to work on, a test to study for. A week later I would meet Katie for the first time. But for that moment, Paul’s hold on my attention was complete.

“The most complicated concept he taught me,” he continued, “was how to decode a book based on algorithms or ciphers from the text itself. In those cases, the key is built right in. You solve for the cipher, like an equation or a set of instructions, then you use the cipher to unlock the text. The book actually interprets itself.”

I smiled. “Sounds like an idea that could bankrupt the English department.”

“I was skeptical too,” Paul said. “But it turns out there’s a long tradition of it. Intellectuals during the Enlightenment used to write entire tracts like that as a game. The texts looked like regular stories, epistolary novels, that kind of thing. But if you knew the right techniques—maybe catching typos that turned out to be intentional, or solving puzzles in the illustrations—you could find the key. Something like ‘Use only primes and perfect squares, and letters every tenth word shares; exclude the words of Lord Kinkaid, and any questions from the maid.’ You would follow the directions, and there would be a message at the end. Most of the time it was a limerick or a dirty joke. But one of these guys actually wrote his will like that. Whoever could decipher it would inherit his estate.”

Paul pulled a single sheet of paper from between the pages of a book. On it was written, in two distinct blocks, the text of a passage written in code, and below it the shorter decoded message. How one became the other, I couldn’t see.

“After a while, I started thinking it could work. Maybe the acrostic with the

Hypnerotomachia

’s chapter letters was just a hint. Maybe it was there to tell you what sort of interpretation would work on the rest of the book. A lot of humanists were interested in kabala, and the idea of playing games with language and symbols was popular in the Renaissance. Maybe Francesco had used some kind of cipher for the

Hypnerotomachia.

“The problem was, I had no idea where to look for the algorithm. I started inventing ciphers of my own, just to see if one might work. I was fighting with it, day after day. I would come across something, spend a week rummaging through the Rare Books Room for an answer—only to find out it didn’t make sense, or it was a trap, or a dead end.

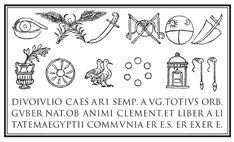

“Then, at the end of August, I spent three weeks on a single passage. It’s at the point in the story where Poliphilo is examining a set of temple ruins, and he finds a hieroglyphic message carved on an obelisk.

To the divine and always august Julius Caesar, governor of the world

is the opening phrase. I’ll never forget it—it almost drove me crazy. The same few pages, day after day. But

that’s

when I found it.”

He opened a binder on his desk. Inside was a reproduction of every page of the

Hypnerotomachia.

Turning to an appendix he’d created at the end, he showed me a sheet of paper on which he’d clipped the first letter of each chapter into what looked like a ransom note, spelling the famous message about Fra Francesco Colonna.

Poliam Frater Franciscus Columna Peramavit.

“My starting assumption was simple. The acrostic couldn’t just be a parlor trick, a cheap way to identify the author. It had to have a larger purpose: first letters wouldn’t just be important for decoding that initial message, they would be important for deciphering the entire book.

“So I tried it. The passage I’d been looking at happens to begin with a special hieroglyph in one of the drawings—an eye.” He flipped several pages, finally arriving at it.

“Since it was the first symbol in that woodcut, I decided it must be important. The problem was, I couldn’t do anything with it. Poliphilo’s definition of the symbol—that the eye means God, or divinity—led me nowhere.

“That’s when I got lucky. One morning I was doing some work at the student center, and I hadn’t slept much, so I decided to buy a soda. Only, the machine kept spitting my dollar back. I was so tired, I couldn’t figure out why, until I finally looked down and realized I was putting it in the wrong way. The back side was up. I was just about to turn it over and try again, when I saw it. Right in front of me, on the back of the bill.”

“The eye,” I said. “Right above the pyramid.”

“Exactly. It’s part of the great seal. And that’s when it hit me. In the Renaissance there was a famous humanist who used the eye as

his

symbol. He even printed it on coins and medals.”

He waited, as if I might know the answer.

“Alberti.” Paul pointed to a small volume on the far shelf. The spine read

De re aedificatoria

. “

That’s

what Colonna meant by it. He was about to borrow an idea from Alberti’s book, and he wanted you to notice it. If you could just figure out what it was, the rest would fall into place.

“In his treatise, Alberti creates Latin equivalents for architectural words derived from Greek. Francesco does the same replacement all over the

Hypnerotomachia

—except in one place. I’d noticed it the first time I translated the section, because I started hitting Vitruvian terms I hadn’t seen in a long time. But I never thought they were significant.

“The trick, I realized, was that you had to find all the Greek architectural terms in that passage and replace them with their Latin equivalents, the same way they appear in the rest of the text. If you did that, and used the acrostic rule—reading the first letter of each word in a row, the same way you do with the first letter of each chapter—the puzzle unlocks. You find a message in Latin. The only problem is, if you make just one mistake converting the Greek to Latin, the whole message breaks down. Replace

entasi

with

ventris diametrum

instead of just

venter,

and the extra ‘D’ at the beginning of

diametrum

changes everything.”

He flipped to another page, talking faster. “I made mistakes, of course. Luckily, they weren’t so big that I couldn’t still piece together the Latin. I took me three weeks, right up to the day before you guys came back to campus. But I finally figured it out. You know what it says?” He scratched nervously at something on his face. “It says:

Who cuckolded Moses?

”

He gave a hollow laugh. “I swear to God, I can hear Francesco laughing at me. I feel like the whole book just boiled down to one big joke at my expense. I mean, seriously.

Who cuckolded Moses?

”

“I don’t get it.”

“In other words, who cheated on Moses?”

“I know what a cuckold is.”

“Actually, it doesn’t literally say

cuckold

. It says, ‘Who gave Moses the horns?’ Horns, as early as Artemidorus, are used to suggest cuckoldry. It comes from—”

“But what does that have to do with the

Hypnerotomachia

?”

I waited for him to explain, or to say that he’d read the riddle wrong. But when Paul got up and started pacing, I could tell this was more complicated.

“I don’t know. I can’t figure out how it fits with the rest of the book. But here’s the strange thing. I think I may have solved the riddle.”

“Someone cuckolded Moses?”

“Well, sort of. At first, I thought it had to be a mistake. Moses is too major a figure in the Old Testament to be associated with infidelity. As far as I knew, he had a wife—a Midianite woman named Zipporah—but she barely appeared in Exodus, and I couldn’t find any reference to her cheating on him.