Read The Tao of Natural Breathing Online

Authors: Dennis Lewis

The Tao of Natural Breathing (8 page)

The “law of least effort” is not, however, a license for laziness. Our health, well-being, and inner growth all require a dynamic balance of tension and relaxation, of yang and yin. They depend on the ability to know through our inner and outer senses what is necessary and what is not in our efforts and actions. To sense ourselves clearly, we need to be able to experience a part or dimension of ourselves that is quiet, comfortable, and free of unnecessary tension. It is the sensation of subtle impressions coming from this more relaxed place in ourselves that allows us to observe and release the unnecessary tension in other parts of ourselves. In short, effective action requires relaxation. But this relaxation should not be a “collapse” of either our body or our awareness. It is more like the “vigilant relaxation” of a cat. Vigilant relaxation makes it possible to manifest the appropriate degree of contraction—the life-giving tension called “tonus”—in any given situation.

THE POWER OF PERCEPTUAL FREEDOM

There are many obvious reasons for learning how to relax unnecessary tension, but one that is often overlooked is that such relaxation frees the brain to notice and respond to a broader, more-subtle spectrum of data and impressions. It is this increase in “perceptual freedom” that can be one of our major contributions to promoting good health in ourselves, since it allows the brain and other systems of the body to make maximum use of their powers in discerning problems and responding appropriately. The hormones, enzymes, endorphins, T-cells, and neuropeptides being produced by the brain and body change dramatically in relation to our ability to perceive in new ways. To be able to perceive in new ways means that our energies are not locked into old patterns, but are free to respond to the actual needs and possibilities of the moment.

There is a wonderful Taoist story that illustrates the importance of perceptual freedom. A man was plodding along a dusty road carrying a long pole on his shoulder with most of his possessions hanging from the ends of the pole. The driver of a horse-drawn wagon saw the man and offered him a ride in the back of the wagon. The man gratefully accepted. As they moved along the bumpy road, the driver heard loud crashes coming from the back of the wagon. When he looked back he noticed that the man was stumbling about with the heavy pole still on his shoulder, bumping into the sides of the wagon. “Why don’t you put down the pole and relax a bit,” the driver suggested. “I don’t want to add any more weight to your already heavy wagon,” the man replied sincerely, trying very hard to keep his balance.

Anyone who has studied martial arts, tai chi, dance, and so on knows that the body is capable of remarkable intelligence, sensitivity, and action when we are able to rid ourselves of unnecessary tension. There is the legend of the tai chi master who was so relaxed, so sensitive to the forces in and around him, that his whole body would sway gently under the impact of a fly landing on his shoulder. And there is the legend of another master on whose palm a bird had alighted; whenever the master sensed the bird tensing to take off, he would simply relax his hand and the bird would have nothing solid from which to take flight. However fantastic such legends may seem, it is the ability to be inwardly sensitive in the midst of action, to be relaxed and free enough to experience subtle variations in our sensations and feelings, which lies at the heart of our health and well-being. And it is through natural breathing that we can begin to experience this sensitivity and freedom.

PRACTICE

Be sure that you practice in a space where you won’t be interrupted by people or phone calls. Though early morning is preferable, you can practice anytime during the day or early evening except for up to an hour after a meal. Wear as few clothes and as little jewelry as possible. Make sure that what clothes you do wear are loose, especially around the waist and pelvis. Do not practice outside if it is extremely cold or windy. When you practice, remember to be playful. Don’t worry about results. As your breathing begins to reach into more parts of yourself, the results will come—usually when you least expect them.

Where appropriate, the practices in this book are divided into sections. Each new section builds on the previous section. Do not move on to a new section until you feel comfortable with the previous one.

1

Basic standing position

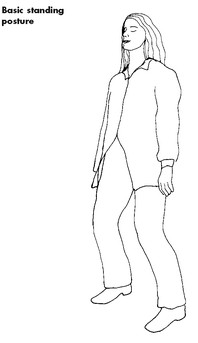

The following standing position will be used not just in this practice but in all other standing practices in this book. Don’t worry if the position seems awkward at first. As you continue working with it, your body will begin to understand it through your inner sensation, and you will find yourself able to relax far more than you can in your normal standing postures. What’s more, the posture will help root you to the earth and provide a stable foundation from which to experiment.

Stand quietly, with your knees slightly bent, your feet parallel (about shoulder width apart) and your arms at your side (

Figure 10

). Tilt your sacrum (the triangular bone that forms the back of the pelvis) very slightly forward, so that your coccyx (tail bone) is more or less pointed toward the ground and your lower back is flat (not arched). Let your knees bow slightly outward so that they are more or less over your feet. As you do this you will feel that both your perineum (the area between your anus and your sexual organs) and your groin are open. Let your shoulders and sternum relax downward and simultaneously feel that your head is being pulled upward from the crown, gently stretching the back of your neck.

2

Awakening attention

Once you are settled in the posture, sense as many parts of your body as you can simultaneously. Then let part of your attention focus on your feet. Sense the various points of your feet on the floor—the five toes, the pads under the big and little toes, the heel, and the entire outside edge of each foot. As you feel your feet relax, sense your weight sinking into and being supported by the earth. Once the sensation of sinking becomes clear, rock gently forward and back on your feet, from the ball of your foot to the heel and so on. Notice how various muscles in your feet, legs, and pelvis alternately tense and relax as your position changes in relation to the force of gravity. See if you can sense any adjustments in your back, your chest, your neck. Now shift your weight from side to side. See if you can simultaneously sense one leg becoming tense while the other relaxes. Let your attention take in as many sensations of these subtle movements as possible. Work in this way for at least five minutes. Then stand quietly for a minute or two and sense any changes that have taken place in your overall sensation of yourself.

3

Basic sitting position

Now sit comfortably, either on a chair or cross-legged on a cushion on the floor, close your eyes, and sense yourself sitting there. Be sure that your spine is relaxed and straight and that you are not leaning against anything. Also make sure that the chair or cushion you sit on allows your hips to be higher than your knees. Rock forward and backward gently on your “sit bones” until you find a relative sense of ease and balance while sitting. Do not slump backward onto your tail bone (coccyx). This area is filled with nerves and is one of the body’s key energy centers. Slumping back on this area will have a deleterious effect on both your awareness and your health. If your spine starts tightening up anytime during the practice, simply rock gently on your sit bones to help relax it.

4

Going deeper into sensation

Once you’ve found a comfortable yet erect sitting posture, let your thoughts and feelings begin to quiet down. One very effective way to support this “inner quieting” is by becoming interested in the overall sensation of your body. Start by allowing impressions of your weight and form to enter your awareness. Really let yourself sense your entire weight on the chair or floor. Once you can feel the weight clearly, include as much of the complete sensation of your skin as possible. When you can feel the tingling, the vibration, of your skin, then sense your overall form, the outer structure of your body, including any tensions in this structure. Sense yourself sitting there, letting your kinesthetic and organic awareness become increasingly alive. As your inner sensitivity increases, you will begin to experience your sensation as a kind of substance or energy through which you can begin to receive direct impressions of the atmosphere of your inner life.

5

Include your thoughts and feelings

Over time, as your sensation becomes more and more sensitive, you will begin to observe your thoughts and feelings as they start to take form—but before they absorb your complete attention. Let them come and go as they wish, but do not occupy yourself with them, analyze them, or judge them. As they come and go, simply include them in your awareness as part of the reality of the moment.

6

Include your breath

As you continue to work in this way, and as your inner attention becomes stronger and more stable, include your breath in your awareness. Follow your breath. Sense any movements or sensations associated with it. Let yourself really feel these movements of inhalation and exhalation, as well as their limitations and restrictions, in the context of the whole sensation of your body. Notice how your breathing influences your sensation of yourself. Don’t try to change anything. Work in this way for 15 minutes or longer. You may want to try this practice morning and night for a week or two before continuing on.

AWAKENING ORGANIC SELF-AWARENESS

As we pointed out in the first chapter, our breath has an influence on all our major organs. Most of us, however, have little awareness of our inner organs. Few of us even know their locations in our body, and our doctors don’t seem to have much interest in showing us. It wasn’t until I reached my late forties that I even knew the difference between my small and large intestines, and where they were located. If you are one of those readers who is not familiar with the location of your organs, take a look at

Figure 11

. Study it carefully, seeing if you can sense the approximate location of the organs in your body.

As you undertake this work of organic self-awareness, it is important to recognize that though the internal organs and tissues are well supplied with nerves, the sensations in these areas are not as strong as sensations closer to the surface of the body, especially the skin. Pain in a particular organ, for example, is often “referred” by spinal nerve segments to other locations, so that it appears that the pain is coming from near the skin.

For example, though it is well known that problems with the heart are often first felt in the arms, shoulders, and neck, it is not quite so well known that the uterus and pancreas refer pain to the lumbar region; the kidneys, to the groin area; and the diaphragm, to the shoulders.