Transmission: Ragnarok: Book Two (41 page)

Read Transmission: Ragnarok: Book Two Online

Authors: John Meaney

**Get the hell away!**

Whether the yell was meant for the enemy or his fellow Pilots, neither Jed nor Max would ever work out. All they could focus on was the need to fly fast and smart, away from the danger behind them.

But they saw the explosion that killed Davey even as they made their transition into mu-space.

EARTH, 1943 AD

The war had disrupted the university’s teaching, but Oxford retained its traditions and procedures. A new year meant the start of Hilary Term, and it was in the fifth week that Gavriela gave her first physics lecture. It was a one-off, and followed from her debriefing with the local atomic bomb developers, sharing what little she had learned in Los Alamos. She had a strong sense that the English programme lagged behind the American effort; by how far, she could not tell.

At tea following that debriefing, discussions of atomic structure and strategies for producing chain reactions naturally gravitated to college politics – though the programme was removed from academia, and its personnel included graduates of the redbrick universities – and then to general matters. A large, walrus-moustached man called Braithwaite delivered his opinion that Oxford would remain free of devastation, not because Hitler wanted to hold back from bombing the venerable sandstone architecture, but because the Luftwaffe’s aeroplanes and Rommel’s tanks were built by German women rather than their menfolk.

Stafford looked at Gavriela, and she found herself speaking.

‘Actually,’ she said, her voice mimicking the languid, fluting arrogance of the men, ‘you’ll find that the well-off German

Hausfrau

maintains her household with the aid of her maidservants, meaning the women are either presiding over drudges or working as such. That’s why they’ll

lose

the war, because Englishwomen are constructing the Wellington bombers that will blow the Wehrmacht war machine to bits.’

‘Well said, my dear.’ That was a narrow-featured man called Sanders, whose unlit pipe perched vertically in his breast pocket like a periscope, as if his unseen heart was peeking at the world. ‘And once the war is won, what do you expect to do? You personally.’

‘Teach physics, I suppose.’ Gavriela blinked. ‘I really haven’t really been thinking about life afterwards.’

At that, Braithwaite snorted and coughed out a

huh

: a walrus-like, barking sound to match his moustache. Afterwards, Gavriela thought that if he had not been so rude, Sanders would not have felt impelled to offer her the opportunity to speak to undergraduates, such few as remained studying while the war continued. Stafford said it was an excellent idea, effectively seconding and carrying the motion.

On the day of the lecture, she was in the room first, ahead of the students. The blackboard was one of the new kind: a tall loop of rubberized canvas stretched over horizontal rollers at ceiling height and floor. She would be able to present an extended train of argument without wiping clear the previous steps. Chalk in hand, she drew a diagram so that it would be ready before she spoke.

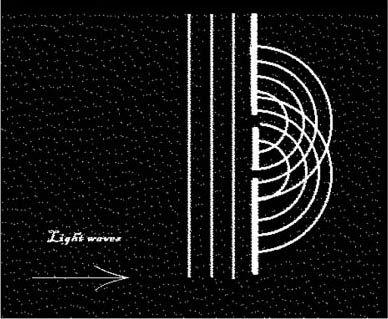

It represented linear wavefronts coming from the left, hitting a barrier with two holes in it, and propagating onwards as two sets of semicircular waves. She would have preferred to back it up with a demonstration, using a water tank with a strong light to illuminate the wave crests, but Sanders had balked when she suggested it. It was too bad, because thinking back to her first day at the ETH in Zürich, Professor Möller’s demonstration of the rubbish-basket Faraday cage had formed a spectacular memory that would be with her always.

When her audience had filed in and sat, she said, ‘Good afternoon, gentlemen. Dr Sanders tells me that you recently discussed wave-particle duality, at which point everyone’s head fell right off.’

She used her most patrician pronunciation –

awf

– and the students laughed.

‘So you’ll know about the double slit experiment’ – she gestured at the diagram – ‘and you see that wherever the semicircular wavefronts cross, two wave-crests are reinforcing each other. If we had a row of little fishing-floats on water waves, you can imagine them bobbing up and down strongly at those points.’

Nodding her head as she mentioned bobbing, she saw the students unconsciously nod in time.

‘In the mid-points between the maximum bobbing, we have places where a wave crest from one gap always meets the bottom of a wave from the other gap, cancelling out. So some of our imaginary fishing-floats remain calm, not bobbing at all.’

Again the nods: they were with her.

‘If this were light waves, and the gaps were narrow slits at right angles to the board’ – she gestured, moving her hand in towards the board, then out – ‘then instead of bobbing floats, we’d have lines of light interspersed with shadow, agreed?’

Nods, still.

‘That is an experimental fact, observed of course by Young in the nineteenth century, and thousands of times since. So the puzzle is, if light is a stream of particles as demonstrated by Einstein among others, then each individual photon can surely go through only one slit. So how does it know about the other slit? In particular, how does it know

never

to go where the two

imaginary

wavefronts cancel out?’

Fewer nods, but they were still with her, because this was in the realm of what they knew but did not understand.

Them and everybody else

.

Gavriela pushed that thought behind her, and focused on the faces, so young-looking.

‘Now Professor Bohr says that reality behaves like either waves or particles, according to which kind of observation we choose to make. In this, he’s factually correct, but only because he’s using the words

behaves like

in a very technical sense. In everyday terms, you

do

get wave and particle behaviour together, and I’m going to show you how.’

She turned to the board and drew an X at random.

‘If we shine light through slits onto a piece of card or a blank wall, we get a series of vertical bright lines. But replace the card or wall with an array of photomultipliers, and we detect exactly where each photon lands.’ She drew another X. ‘And that seems pretty particle-like to me.’

Moving apparently at random from right to left across the board, she drew some four dozen Xs in total. A pattern was emerging, and so was comprehension on the students’ faces.

‘As we keep track of the points’ – she drew two more – ‘we see that they gradually build up the vertical lines of light that we expect. Wave behaviour grows from the particle behaviour, while the particles followed wavelike constraints.’

It was time to explore the Schrödinger equation, which would lead to discussing the difference between electromagnetic waves and the ψ waves that the equation dealt with: a varying quantity specified by two numbers, like longitude and latitude combining to give a map location, from which a probability could be worked out. But before that, she needed to ensure her audience was with her psychologically.

‘I hope I’ve thrown some light on the subject’ – she waited for the smiles and groans – ‘and leave you to consider later how new patterns arise from increasing observations, and how, for the Sherlock Holmes devotees among you, it’s the places where the light may

not

shine that define the pattern, making it depart most strongly from classical reality, so that … that …’

She shivered, hearing nine discordant notes, but only in memory, not in the moment; and knew that her words meant more than intended.

‘… the darkness defines the light.’

After a moment, she was able to continue, but not without awareness of a strange, unfocused image lurking at the back of her mind.

Dmitri travelled in civilian clothes, not uniform, but his papers identified him as a member of the SS. His biography was well established in the Berlin archives, planted there by a V-man who was in fact a double agent: embedded in the Reich’s intelligence hierarchy but run from Moscow. Dmitri’s orders were to rendezvous with a contact in Kreisau, then decide on his own initiative whether to attempt an infiltration of the group in question.

The preliminary intelligence was that local high-ranking officers intended to attempt assassinating Hitler. Dmitri’s cynicism noted that such sentiment was rising now that the Wehrmacht no longer seemed unstoppable: not just their faltering against Moscow, but their destroying less than fifty Allied ships in the North Atlantic during the previous three months, in contrast to the six and a quarter million tonnes of shipping sunk in the prior year.

He knew those figures were accurate. He had purloined them himself via an asset among Admiral Canaris’s staff, and passed them on via courier to Moscow.

The German theatre of operations was where he belonged. His linguistic expertise and cultural knowledge meant that he should never have been sent to Japan; except that it had been a fortuitous posting, far from internal politics: his former superior, Colonel Yavorski, was no more. That had been the gossip from the case officer running the Frankfurt network and engaged in courier work on the side, hence his meeting with Dmitri.

The compartment door rattled open.

‘

Ihre Papiere, bitte

.’

Dmitri had no qualms as he handed over his ID for inspection. He could fit in here. If Germany won the war, he intended to become part of the establishment; meanwhile, he would continue to perform for his Soviet masters. While the more he quelled his desire for murder and the taste of human meat, the less hold his

other

master seemed to have on him. Or perhaps it did not care to direct him any more.

Perhaps, by his nature, he furthered its purpose no matter which side he took in humanity’s ephemeral, parochial affairs.

They worked in caverns below ground, a legion of the lost, each of them in the process of being broken down by workload and cold and starvation, each man a unit to be replaced: corpses were one of the waste products of Peenemünde; and Erik Wolf was just one more temporary component among the damned.

He did not believe in the concept of life force, of an

élan vital

; but there was a shining thought that kept him from death for now, and it was the conviction that Ilse had got away, using the loft that ran through to the house next door, before the Gestapo had come pouring in. There were no illusions: for him, it was only the work-gang and suffering, with death at the end.

But it lasted longer than he had expected, moving from digging and rail-laying to work that demanded more nimble fingers: fastening components inside metal casings of what looked like huge finned torpedoes, designed for flight. The insides had the clunky functionality of refrigerators or cars, robust and inelegant.

‘What is

Vergeltungswaffen

?’ muttered one of the other prisoners, a Russian.

They could get away with mumbled conversation from time to time, provided they remained bent over their work and did not stop assembling the hardware.

‘You understand “revenge”?’ said Dmitri.

‘Sure.

Mest

. I understand.’

‘Weapon of revenge, then.’

The Russian, his face lined and collapsed like everyone else’s, became even more grim.

‘Aeroplane bomb without pilot,’ he said.

‘Yes.’

The missiles were to be called reprisal-weapons, propaganda for the people at home who were suffering now as Allied bombers encroached on the Reich’s airspace, the name a joke to any non-Nazi. But the weapons themselves were deadly, urban populations their target.