William Falkland 01 - The Royalist (21 page)

Read William Falkland 01 - The Royalist Online

Authors: S.J. Deas

I read on:

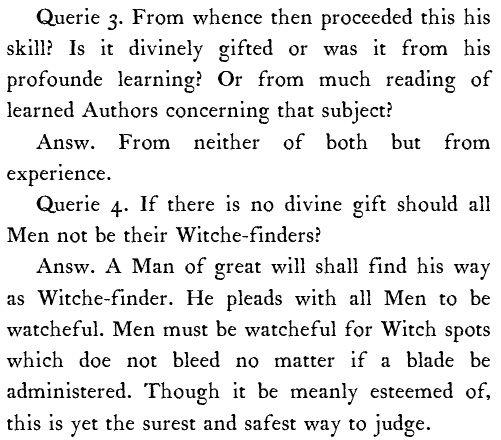

I meant to read on, for now there was something compelling about the answers Hopkins gave as narrated by his companion John Stearne. It sounded to me like the same vindictive railing I’d seen in this camp and indeed across the country – of one kind of man taking joy in torturing another. Yet as I squinted at the papers, a sudden sound tore me away. I stood up. The sound came again and I had the instinctual sense that I was cornered as I’d been outside Abingdon when I was finally captured.

The sound came again and I realised that somebody was tapping very softly on the shutters across my window. My hand went to my hip but I had no dagger there and never would have while I remained in this camp. I crept to the shutters and lifted the latch to see who was outside. I will admit that a large part of me feared a rock thrown through the window or for musket fire lighting the night. At once the very idea seemed laughable – an assassin does not announce himself by tapping at a window as though he’s your long-lost love; still, my heart pounded in my breast, its thunderous rhythm instructing me that I was too old and weary to fling myself about like a young man.

I drew myself up and craned out into the night. The sky was overcast and swollen with snow. Indeed, thin flakes were falling already, presaging a tumultuous fall to come. I could smell it in the air. In the street in front of me stood a figure. At first I could make out little but his frame, tall and spindly. He wore a coat fastened high around his neck and great gloves that made him appear bigger than he was. He had no hat but his hair was frosted with sparkling crystals of ice.

‘Who goes there?’ I hissed. I could see only a vague outline of his face. He had a nose like a hawk.

‘Are you the intelligencer?’

That word was beginning to grate, no matter if it was true. All the same I told him he was correct.

‘Sir, you must come with me.’

‘Come with you where?’

‘Sir, please . . .’ His voice seemed suddenly frayed and I wondered if his baritone commands of only moments ago had been an act he was finding hard to continue. ‘Must I beg?’

I risked glances up and down the street. All was dark and I could see no other man abroad, not even a camp guard making his rounds. From here I couldn’t even see the light of the fires that surrounded Crediton. The world appeared strangely at peace. ‘No,’ I said, ‘not beg.’ I paused. The man shifted uneasily from one foot to the other. I still couldn’t see his face. ‘But what is this about?’

His voice broke. It was only then, in the way he croaked his words, in the way he had to force them out, that I knew he was genuine. ‘Thomas Fletcher,’ he finally said. ‘We saw you by his old home. We heard you were . . . asking questions. If you want to know how he died, you’ll come with me.’ He paused once again. ‘Please, sir.’ Again his voice faltered. I could not tell whether he was dread fearful or distraught. Either way, I owed it to those dead boys to hear what he had to say.

I nodded my assent and closed the shutters.

Alone in my room I took haste to dress myself and put on my boots, forcing my swollen feet into each one. Thomas Fletcher, they told me, was not a boy with many friends. What friends he had were his family and they were gone already. I didn’t know who the soldier in the street was but I was certain of one thing; he was not the sort of man to befriend a small, cowardly boy like Thomas Fletcher.

I crept along the hall and up the stairs past Warbeck’s door. Outside Miss Cain’s room I stopped. My hand hovered on the handle. I wanted to push in, to wake her and tell her where I was going, yet I hesitated. The worst of it was the reason – that a very large part of me wished I’d returned here some hours before.

I tapped on the door and turned the handle. I could hear her breathing now, soft and steady, quietly asleep. I eased into the room. At once she stirred.

‘Falkland . . . ?’ she whispered, rising and turning to me. She was wrapped in a shawl but wore little else. In the gloom I couldn’t see the swollen patterns of her face.

‘Miss Cain,’ I began, ‘I’m sorry to have woken you.’

She rubbed her eyes and showed no alarm that I’d crept into her bedroom in the dead of night. As I came closer she reached out a hand and touched my leg. I was suddenly glad of the man waiting down by the door.

‘There is something I must do,’ I said.

She drew away. I sensed her puzzlement.

‘Kate, there’s one thing you might do for me.’

‘What is it, Falkland?’

‘Miss Cain,’ I said. ‘I shall need a knife. A dagger would be best but a blade from the kitchen would suffice.’

CHAPTER 20

The soldier in the street was impatient. He stood some distance from the house and beckoned me to join him. As I approached, I felt for Miss Cain’s scullery knife secreted at my back and did as I was told; it was only as I came close that the starlight finally pulled his face from the shadows and I recognised him: Lucas, the surgeon. It had only been days since I’d seen him, a man no older than twenty-five suddenly in charge of all the invalids the New Model coughed up, but it seemed much longer. If he knew who I was or recognised me from that day as I did him, he was working hard not to show it. He barely fixed me with a look as he turned and began to shuffle away.

‘You treated Thomas Fletcher,’ I began, ‘after he was found?’

He mumbled something I didn’t catch and led me along the street, past the inn and the chestnut tree with its hanging man. Over the rooftops I could see the spire of Crediton church and then at last the glow of red and orange from the fires pitting the encampment.

‘Did you treat the hanged brothers too?’ I asked.

I was getting used to the idea that he didn’t want to respond when he stopped, dug his heels into the snow and turned. It was only a half-turn, just enough for me to make out his lips. He kept his eyes downcast. ‘There wasn’t any treating to do,’ he said. ‘I’m a surgeon, not a sorcerer.’ He was trembling, and not simply from the cold.

‘Not a

witch

,’ I breathed, remembering the pamphlet.

I stirred a reaction in him but not one I expected. His face screwed up and his eyes lifted and for a second it seemed as if his gaze was locked into mine. There was terror in those eyes. It was the terror of a little boy on a dark night, camping out with his father with a head full of stories of devils and their familiars. It seemed laughable that a grown man could recreate such an expression, but there it was.

‘You should not talk of the dead,’ he whispered.

He led me on a familiar route along Main Street. The snow began to fall in ribbons of white. The further we walked, the more thickly it came down, until I wondered if we’d crossed the frontier one storm makes with the next. I was thankful there was no wind to whip it at my face but it was hypnotic. There’s a magic in falling snow. It makes all the world seem the same, even if underneath one patch of ground is vastly different to the other: one corner for the roundheads, one corner for the cavaliers; one corner for the Puritans, one corner for Catholics clinging to their rosaries and praying not to be discovered.

We passed close by Mrs Miller’s home and came through the last of the Crediton cottages. The sprawl of the encampment tents spread out before me. Even at this hour of night it felt like day, for the whiteness of the snow made the tents visible to the very horizon, brought close by the encroaching blizzard. There was movement in the camp too as soldiers, stirred from restless sleep by the snowfall, rushed to stoke their fires and make sure they saw it through the night. Men can get used to the worst deprivations. I’d learned that in prison.

We followed a weaving trail through the tents to join a track I’d taken once before on that very first night with Miss Cain. She was without doubt a better escort than the surgeon Lucas but at least I knew where I was going. It already seemed so very long ago.

We left the camp and crossed the acre of land beyond its border. We plunged above our knees into the snow. Drifts were building again. If the blizzard continued through the night then in places those drifts would climb as high as my head by morning. In the distance I saw the witching tree. Thinking of its name like that set new mechanisms whirring in my head. The word

witch

seemed, all of a sudden, to have different and less idle meanings. It was probably trees like this that Matthew Hopkins used to string his sorcerers up while baying crowds gathered round. Tonight the tree was a black silhouette crowned in deeper and deeper white. As we approached it seemed to grow more stark, to leap out at me, pitch-black against the swirling snow.

Twenty yards away and with the falling snow a shifting curtain between us and the old oak, Lucas put out his hand and bade me stop. No sooner had I done so than the snow began to settle on me, frosting my eyebrows and eyelashes, caking my skin.

‘He’s waiting,’ Lucas said.

I squinted. There was another figure in front of the tree. That was all he was to me now, but something made me move my frozen hand to the handle of the knife at my back. My fingers were stiff but they closed around it tightly. It was enough to know I could draw it if I needed. ‘You’re not coming?’ I asked.

Lucas shook his head. ‘I want no part of this, Falkland. Besides, the cold will kill us as easily as a granadoe being lit.’ He shivered.

I nodded and left him behind. It took an age to cross those measly twenty yards. The snow had not been walked upon – where the man at the tree had come from, I couldn’t yet tell – and I had to kick my way through. Where the granadoe had exploded, the depression in the land still showed, the snow piled higher in the crater so that I plunged suddenly and stumbled, falling into what felt like a pit. When I recovered my feet, the snow in the crater reached my waist. I fought my way free but the ice clung to me and I could feel it seeping into my bones.

The figure waited on the opposite side of the tree but moved around as I approached. I was glad we didn’t stand beneath the very branch where the brothers and Hotham had hanged themselves high. I stopped my eyes from even glancing that way; I was cold enough without having to bear another chill.

‘I’m glad that you could come.’ The voice was measured. Calm. I knew it at once.

‘Carew,’ I whispered.

‘I’m glad to meet you again, Falkland,’ he said, extending his hand. ‘Would that it were in less trying circumstances.’ His voice didn’t tremble as I knew mine would, in spite of the cold. He moved nearer but I couldn’t see his face. All around us the world was illuminated by snow – but here, underneath the crown of white lodged in the branches, we were only outlines in black. He held himself like a lord, less like the roundhead pikeman I’d first taken him for and more like the fey cavaliers with whose image they mocked the King’s army. He had the vestiges of a London accent – though it seemed to my ears a tone relentlessly rehearsed – and when I took his hand, I found it limp this time, the touch too light. Perhaps it was only that both of our hands were frozen inside our gloves but something seemed awry in that pose.

‘I was told you knew things about Thomas Fletcher,’ I said. ‘So what’s this about? And why the forsaken hour?’

‘A sorry tale.’

‘A tale that might easily have been told in front of a fire with ale in our hands and pottage on our plates . . .’

‘And have the whole camp hear?’ he replied, rising in a shrill peak but holding back from laughter. ‘No good could come from that.’

‘The surgeon’s quarters then. Surely we might have spoken there?’

I was suddenly aware of the pamphlet still stuffed into my pocket. I pictured Carew and Hotham working the press, arranging the letters, fixing the paper. In my head, Thomas Fletcher scurried around them, obeying orders thrown at him from left and right.

‘Jacob would have been disturbed,’ Carew replied. ‘And there are too many boys lying there. I don’t want the story told too freely.’

‘I know you knew Thomas, Carew.’ A wind flurried up, throwing a veil of snow between us, and for a moment it robbed my breath. ‘But you know I know as well.’

‘I wasn’t sure you had recognised me.’

In truth I hadn’t. It was only as I looked at him now that it occurred to me: he had exactly the same lean, willowy figure as the hooded man I’d chased from the Fletcher house before I was drawn, instead, to old Beatrice Miller. Carew had been there all the while. And Beatrice Miller had known it too and quietly never said a word. Somehow it felt as if we were parrying blades, with me forced onto the back foot. ‘You might have told me,’ I ventured, ‘when I first came to see Jacob, that you knew Fletcher as well. You were not honest, Carew. Why was that?’

I could see him weighing up the words he was about to say. ‘You must forgive me, Falkland. These are trying times.’

‘All the same, it was a lie. You told me you knew only his story, yet all the while he was your messenger boy, delivering your –’ I checked myself from saying pamphlets: there was still a chance I didn’t know that part of the story – ‘Bibles to the soldiers.’

‘That was how White Tom and Jacob knew each other.’ Carew came closer to me. I hated to admit it but I was thankful. Together we formed our own windbreak, turning against the worst of the chill. No longer did we look at the witching tree; instead, we gazed over the endless white. ‘We didn’t know it was Fletcher’s house. Not to begin with. He was just some simpering royalist whelp who started loitering around. But we had our use for him. We were turning out more books of verse than we—’

‘The printing press,’ I interjected. ‘Where does it come from?’

Carew’s lips curled. He seemed to be enjoying a joke at my expense. ‘Why, Falkland,’ he said, as if the answer was so obvious that a child might have known it. ‘It belongs to the New Model.’

‘The army has its own press?’

‘How else is it to lead its soldiers? We are not barbarians. We are –’ and here he could not but grin, for he was driving a stake into what he presumed was my unending loyalty to the King and Prince Rupert – ‘not

minions

. There can be little opportunity for a printing press when the army is campaigning. But in a winter like this the contraption has a part to play that is much, much bigger than any individual soldier.’

There was truth in this. He didn’t know that I already understood, but he wasn’t only talking about Bibles and books of pocket verse. The pamphlets, I was beginning to understand, were as much a way of controlling the men, cut from disparate towns and disparate militias, as was drilling and the rule of soldier’s law. The pamphlets cut away all mention of the King from the traditional Oaths. They filled their pages with images of Prince Rupert as a devil and his dog as his familiar and other such. These were not idle thoughts. These were careful manipulations. Yet as I looked at him, I was suddenly aware of how young he was. War is a time for young men to make bold, to climb high, to be ambitious and stake claims from which they can build their future lives. I suppose, in a way, that was what I’d done, though I’d not planned on it and didn’t care much for where it had brought me. All the same, Carew did not seem to me to be a man in any way in charge of this army. For all his airs, he was common soldiery.

It dawned on me then that perhaps Cromwell wasn’t the astute tactician he seemed. If a weapon as powerful as the printing press – for, make no mistake about it, this was a weapon far more powerful than any granadoe – was left for boys to employ, then the New Model was not as clever as he believed.

‘Why you?’ I asked.

The question must have caught him off guard. ‘Falkland?’

‘Why are you running the press?’

‘Not me,’ he said. ‘Jacob. He is an esteemed sort of man. Knows the presses inside and out from his days in London. He fancied himself a poet, you see. Or, if not a poet, a polemicist. When we came to camp he was asked to help in the binding of the Bibles but it quickly became clear that he was much more useful than that. He asked me to aid him.’ Carew paused. A shiver ran through him; we’d been out in the cold too long. ‘He’s fortunate that he did. If I’d not been working the press with him, I would not have been there to save his life.’

I remembered what Carew had told me the last time we met – that they had been working a watch around the camp, that Hotham had taken himself to the witching tree where we now stood and strung himself up there only for Carew to have a vision from God and come running with his fellows to cut him down. My eyes began to stray back to the branch from which the rope had dangled but Carew ploughed on:

‘It was because of Thomas Fletcher,’ he said. ‘It was all because of him. You know, by now, that the house we use for printing was where he grew up. Well, he came there often. We took pity on him at first. He was hardly more than a boy and certainly he didn’t have the ideas and thoughts that might belong to a man. So we thought it little danger to take him in. We did not let him near the press but he was useful enough as a messenger—’

‘And a courier.’

Carew ploughed on, heedless of my interruption. ‘He became something of a little brother to us. One night we had a wineskin and offered it to him. Do you know, I believe that until that moment the only wine to ever touch his lips had been from some secret communion in that treacherous little church of theirs. Still, he took to it with aplomb. You will think it cruel but it became a game for us, to taunt him and see how far he might go. We decided to share some stories. Jacob is a man with many stories to tell and I will admit to having my own tall tales, but Thomas Fletcher – well, a more naïve, hopeless boy you’ll never meet. You see, Falkland, it became clear to us that Thomas Fletcher was

innocent

of things a soldier must not be innocent of. I don’t mean killing a man . . .’ He said it with a lascivious grin, his mouth open a fraction too wide like a glutton contemplating his supper.

‘I know what you mean, Carew,’ I said.

‘There are lots of sorts around here to take that innocence from a boy. So we took him to see a girl we knew.’

It didn’t strike me as right that a boy like Carew, so fiercely Puritan in his outlook, would have fraternised with camp whores. I remembered distinctly the way he’d looked on the Day of Admonishment, not baying like the rest of the crowd but somehow pleased nonetheless. I met his eye. ‘Then I’d like to talk to her. Who was she?’

I had it in mind that he’d answer ‘Mary,’ and before he’d even spoken the word, ideas exploded and reformed in my head. If Fletcher had wandered into the same ménage as Richard Wildman and his brother then perhaps there was something other than their Catholicism to draw all these boys together after all: three boys enamoured of the same whore? Jacob Hotham the one who spun the spider’s web . . . ?