Read You're Never Weird on the Internet (Almost) Online

Authors: Felicia Day

You're Never Weird on the Internet (Almost) (5 page)

I called myself Leesie as a kid because I guess my family couldn’t think of a more unattractive nickname. Oh wait. My grandpa called me Pooch. That one I won’t embrace in print.

But the way I wrote to this diary, you’d think I was writing on the mirror to another little girl who existed on the other side of the page.

“Dear Diary, it’s been a month since I wrote. I know, I’m a bad friend.”

“. . . I finished the

Emily of New Moon

books this week, but I mustn’t bore you.”

“Today’s our first anniversary. Happy Birthday to us!”

I confided everything a weird sixth-grader would share with other children and definitely be rejected for in a typical school situation. Big dreams like, “Wouldn’t it be neat to go back to 1880 and there wasn’t any kidnappers and progress, and the streams and fields and everything were beautiful?”

I made super-serious vows in the margins, like, “Vow: I will never kill an animal if I can help it.” “Vow: I will never marry a man for money.” “Vow:

I will never let my children live in a slum.” Real personality-congealing self-work.

My mom was a big political activist, and that rubbed off on me in a big way, too. The diary is awash in bold political statements and social consciousness.

“We have a new president. George Bush and Dennis the Menace for vice president.”

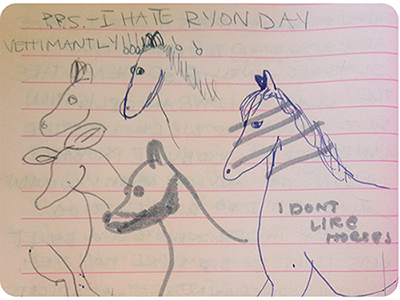

Most of all, the diary was a safe zone. A place where I could share my innermost thoughts, work out a semblance of an identity, analyze my likes and dislikes, and work through my relationships, like that with my brother, Ryon, in a thoughtful, mature way.

That little pink diary is a tome for the ages.

My mother wasn’t totally blind to the fact that we needed exposure to other kids. She made efforts. But none of them seemed to stick. Probably because my attitude toward other children was like a seventy-year-old spinster’s.

“This girl Kate from violin lesson came over and I told her about my books. She doesn’t read. Stupid. I won’t explaen [

sic

] them to her. She has no imagination.”

“We went to eat with Miss Molly’s two kids today and they were putting forks on the floor and stepping on them like hoolegans [

sic

]. We also took Samantha (10) who is fat and obnoxious, but nice when she isn’t giggling insatatiabley [

sic

].”

“I went to an opera-ballet by myself. Behend [

sic

] me were two 7-year-old giggling brats. Well, gotta go!”

The only kid in real, close proximity to me was Erin, a thirteen-year-old who lived next door. She taught me that owning a trampoline was the most glamorous thing a girl could have, and that jelly shoes were haute couture. I learned all this through spying on her through my bedroom window, because she didn’t like me and wouldn’t spend any time with me, physically.

Despite our strained relationship (or because of it), I did have strong thoughts about her lifestyle choices.

Then I went on to apologize about criticizing her behavior, because I think my diary started chiding me about my judgmental attitude. Somehow.

Upshot to my bizarre upbringing: I got super-hyper-educated in many odd areas but was pretty lonely for many years. Sometimes achingly so. They say that the root of everything you are lies in your childhood. Every emotional problem, every screwed-up relationship, every misplaced passion and career problem you can blame on the way you were raised. So I can be kinda smug when I say, “Boy, do I have some excuses!”

Sure, I could have avoided a lot of problems as an adult by being raised like everyone else. I might not have had as much performance anxiety, I might be better at maintaining relationships outside of hitting “Like” on a person’s Facebook post when they have a baby. But here’s the part I unapologetically embrace: My weirdness turned into my greatest strength in life. It’s why I’m who I am today and have the career I have. It’s why I’m able to con someone into allowing me to write this book. (Hi, Mr. Simon and Mr. Schuster!)

Growing up without being judged by other kids allowed me to be okay with liking things no one else liked. How else could a twelve-year-old girl be so well versed in dragon lore and film noir? Or think it was the height of coolness to be able to graph a cosine equation? Or long to play Dungeons & Dragons but never get the chance until adulthood because her mom saw that one article on how it made you a Satanic basement murderer?

Most school situations would have shamed all those oddball enthusiasms out of me REALLY quick. Those bow-girls would have snubbed me for them, for sure. But during my childhood my fringe

interests remained uncriticized, so they bloomed inside of me without self-consciousness until I was out in the world, partially formed, like a blind-baked pie shell. By then it was WAY too late. I was irrevocably weird.

I’m glad I didn’t know better than to like math and science and fantasy and video games because my life would be WAY different without all that stuff. Probably “desk job and babies” different. Not that there’s anything wrong with babies. Or desks. I mean, I’m sitting at one now, so my analogy really doesn’t . . . I didn’t mean to insult anyone with those things, I just . . . oh gosh, panic sweats.

Anyway, thanks for all the weirdness, Mom and Dad!

P.S. I don’t have a GED. I have two college degrees, but I don’t actually have a high school one.

It took writing this chapter to figure that out. Fuck.

- 2 -

What Avatar Should I Be?

Forming my identity with video game morality tests. And how that led to my first kiss with a Dragon in a Walmart parking lot.

Knowing yourself is life’s eternal homework. ( Another coffee mug slogan!) We have to dig and experiment and figure out who the hell we are from birth to death, which is

Another coffee mug slogan!) We have to dig and experiment and figure out who the hell we are from birth to death, which is

super

inconvenient, right? And embarrassing. Because as teenagers we do all that soul-searching through our clothing choices. Which we later have photographic evidence of for shaming purposes. Hippie, sporty, goth, I have an adorable sampling of all my more mortifying phases.

That “mom jeans” picture calls for a postview eye bleaching, huh?

Because I was homeschooled, there are huge holes in my identity that I constantly have to trowel over. Answers to basic, “truth or dare” questions like:

▪

If you could trade places with one person for a day, who would it be? (I guess Beyoncé because . . . amazing hair reasons?)

▪

If society broke down, what store would you loot first? (A drug store for tampons? Sorry, dudes, for mentioning tampons in the book.)

▪

What kind of tattoo would you get? (Um . . . a hummingbird-fairy-dragon creature? Legolas on my right ass cheek? I HAVE NO IDEA, STOP PRESSURING ME!)

I AM covered in the “What superpower would you wish for?” area. I’ve been asked that question a million times, because, you know, the nerd thing. I would want to be able to speak all languages. I don’t even know ONE other language outside of key menu items like “tamale” and “fondue,” but whenever I hear a tourist who can’t speak English struggling to get directions, I dream of being able to step in, no matter what the language, but especially German since it’s emphatic, and fix the problem. Then I accept their thanks with a wave of the hand.

“Es ist nicht, mein freunde!”

In my imagination, I meet a lot of amazing people this way, especially heiresses of castles whom I visit in Europe the following year, anointed as “The American who saved my vacation last summer.”