109 East Palace (10 page)

Authors: Jennet Conant

Throughout those rushed months of planning, Rabi and Bethe, among the wiser, more experienced hands, worked on Oppenheimer, urging him to convert his abstract thoughts about the project into a workable plan on paper. Without Rabi’s practical advice, Bethe said, “It would have been a mess”:

Oppie did not want to have an organization. Rabi and [Lee] DuBridge [head of the physics department at the University of Rochester] came to Oppie and said, “You have to have an organization. The laboratory has to be organized in divisions and the divisions into groups. Otherwise nothing will ever come of it.” And, Oppie, well, that was all new to him.

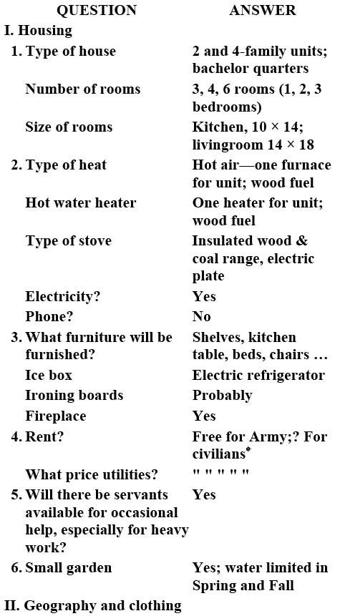

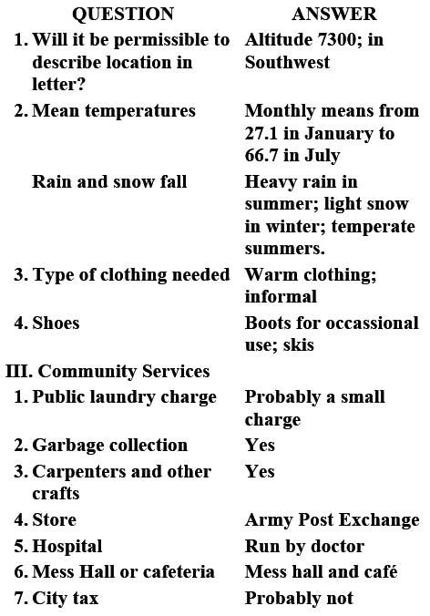

Rose Bethe, whom Oppie asked to run the housing office at the new installation, probably had a better idea than most about what they were getting themselves into, having already toured that part of New Mexico and having received in late December a long letter from Oppie addressing some of her questions about the living conditions. His warmth and concern were touching, but his rough sketch of their hypothetical mountain hideaway, which read in places like something out of

Boy’s Life

, was hardly reassuring, nor was his airy promise to keep her list of questions “as a reminder of what we shall have to do”:

There will be a sort of city manager. … There will also be a city engineer and together they will take care of the problems outlined by you. We hope to persuade one of the teachers at the school to stay on to be our professional teacher. It is true that both Kay Manley and Elsie McMillan are professional school teachers and there will no doubt be others, but it seems to me very unlikely that anyone with a very young child will be able to devote very much time to the community. There will be two hospitals, one in town and one in the M.P. camp….

Room is being provided for a laundry; each house will have its washtub; and we shall be able to send laundry to Santa Fe regularly. It may be necessary for us to provide the equipment for the group laundry since this is now frozen, but this is a point that is not yet settled.

We plan to have two eating places. There will be a regular mess for unmarried people which will be, when we are running at full capacity, just large enough to take care of these. The Army will take care of the help for this and I do not know whether the personnel will be Army or civilian. We will also arrange to have a café where married people can eat out. This will probably be able to handle about twenty people at a time and will be a little fancy, and may be by appointment only. We are trying to persuade one of the natives to do this and we have a good building for it.

There will be a recreation officer who will make it his business to see that such things as libraries, pack trips, movies, and so on are taken care of…. The store will be a so-called Post-Exchange which is a combination of country store and mail order house. That is, there will be stocks on hand and the Exchange will be able to order for us what they do not carry. There will be a vet to inspect the meat and barbers and such like. There will also be a cantina where we can have beer and Cokes and light lunches….

Oppenheimer concluded by saying that he was “a little reluctant to do too much writing about the details of our life there until people are actually on the job.” He added that he had done his best to provide some rudimentary information in the enclosed sheet and that she should let him know “if any of the arrangements that we have made so far are definitely unsatisfactory.”

All that winter, Oppenheimer’s home at One Eagle Hill Road, just north of Berkeley, became the project’s informal headquarters, where he and Kitty played host to a steady stream of visiting scientists. Their house was a handsome, Spanish-style ranch, perched on a steep incline high above the city, with lush gardens and a sweeping view of San Francisco Bay below. The home was expensive and tasteful, decorated with fine oriental rugs and art, and bespoke a lifestyle few academics could afford. Oppenheimer might have calculated that this would play to his advantage, making him appear to be more of a strong, established leader as he surged ahead in his new role as Los Alamos’s director. Serber, who had moved back to Berkeley with his wife, Charlotte, to help with the bomb project, had taken up temporary residence in Oppenheimer’s garage apartment, and so after office hours, Eagle Hill became the place to gather. Much of the early planning for the new laboratory was done there over Oppie’s superb “Vodkatinis,” which were expertly prepared and generously distributed.

Standing in front of the fireplace, jabbing at the air with his large pipe to emphasize a point, Oppie would expound on his plan to have about thirty physicists go off together to the desert to build the bomb. According to his utopian vision, most of the support jobs, such as the secretarial and administrative positions, would be filled by the scientists’ wives, to keep outsiders to a minimum and assure security. “We shall all be one large family doing vital work within the wire,” he assured them, sounding uncomfortably like the army propaganda films running in the local movie houses. Greene recalled late nights and long, rambling conversations between Oppie and Serber about whom he should invite to join the team, which physicists were talented and resourceful enough to tackle the obstacles ahead, and whose intellectual powers might have a catalytic effect on the less qualified. Oppie might as well have been Noah lining up exotic creatures for his ark. When Charlotte Serber overheard them making plans one night, she told them, “You aren’t really serious? You fellows don’t think you’re going to run a project like this, you must be out of your minds!”

Back in Washington, Groves’ bright young assistant, Anne Wilson, asked him to tell her what the newly appointed director of Los Alamos was really like as a person. Groves’ office was run with steely efficiency by his administrative assistant, Mrs. Jean O’Leary, but Wilson’s desk was just outside the door to Groves’ office, and as Anne was very good-looking, Oppenheimer had often stopped to chat her up. She found him fascinating. His reputation as a dashing and urbane ladies’ man was already legend within the War Department, but she wanted to hear Groves’ blunt appraisal. They were traveling to work together that morning as usual, and as was his custom, the general drove while she read the papers aloud to him. He always insisted on beginning with “Mary Haworth’s Mail,” the

Washington Post

’s high-class advice-for-the-lovelorn column, followed by the sports pages, so that they did not get to the front page until they were practically pulling up to the office. Wilson knew her question was a little impertinent, and had Groves decided to ignore it completely, she would not have been surprised. At the same time, theirs was not the usual secretary and boss relationship: her father was an admiral, and she had grown up around the corner from Groves in Cleveland Park, in D.C., and she often played tennis with him at the Army-Navy Country Club. Groves was used to her boldness, and he teased her about it incessantly. He drove in silence for a few minutes, and when he finally answered, Wilson was so taken aback by what he said she never forgot it. “He has the bluest eyes I’ve ever seen,” Groves told her. “He looks right through you. I feel like he can read my mind.”

No matter what one person saw in Oppenheimer, another would assert the opposite was true. But that he possessed a certain brilliance, and a signal capacity for leadership, few would deny. Almost no one was neutral about him. “Oppenheimer was a very clever politician,” said Teller grudgingly. “He understood people. He essentially knew how to influence them.” He may have been the consummate actor, as his critics contend, questing after power, and calculatingly turning to Groves a face he knew the general would favor. Or he may have had so many masks that he lost track of his true self somewhere along the way. But for all of his intellect and ambition, he could be maddeningly obtuse at times, even careless, as if somehow unaware that the same rules applied to him as to everyone else. It may simply have been that the Manhattan Project was too big an adventure for Oppenheimer not to take part in, no matter his qualms or private misgivings. He had always hankered after a certain kind of authenticity, a defining experience. He had to be “near the center” of things; that very impulse, he once admitted to a friend, which had originally moved him to leave chemistry and Harvard for Cambridge’s Cavendish Laboratory, mecca for bright young physicists.

Pressed into service, Oppenheimer rose to the challenge. Eloquent, inspiring, and elusive, perhaps deliberately so, he became the pied piper of Los Alamos. By the end of 1942, he had passionately embraced the bomb project as a means of ending the war, and was using all his wiles and powers of persuasion to entice the most important physicists in the world to leave their jobs, uproot their families, and join him on that lofty mesa in New Mexico. “Almost everyone realized that this was a great undertaking,” he later wrote of the hundreds who followed him into the desert:

Almost everyone knew if it were completed successfully and rapidly enough, it might determine the outcome of the war. Almost everyone knew that it was an unparalleled opportunity to bring to bear the basic knowledge and art of science for the benefit of his country. Almost everyone knew that this job, if it were achieved, would be a part of history. The sense of excitement, of devotion and of patriotism in the end prevailed. Most of those with whom I talked came to Los Alamos.

FOUR

Cowboy Boots and All

W

HEN DOROTHY MCKIBBIN

reported to work at 109 East Palace Avenue on March 27, 1943, the morning after the meeting in the lobby of La Fonda, she found Robert Oppenheimer waiting for her on the other side of a shabby screen door. He was as polite and disarmingly solicitous as he had been that first day, but his face was pale beneath the sunburn, and on close inspection, he appeared tense and drawn. She had sensed from the beginning that this was going to be no ordinary job, but that impression was powerfully reinforced by the presence of two Spanish Americans standing guard by the door armed with rifles. From his few comments, it was also clear that Oppenheimer already knew all about her, which was why he had been able to hire her so casually on the spot, without any question or hesitation. Much later, she realized that he had probably already reviewed a full security dossier on her and had strolled across the lobby for the express purpose of looking her over.

The ground-floor offices, which Joe Stevenson had leased the previous week, were housed in a venerable adobe building one block north of La Fonda, in one of the most ancient sections of the old city. The faded blue portal and three-foot-thick walls dated back to at least the late 1600s, when the property was deeded to a Spanish conquistador, Captain Don Diego Arias de Quiros, as a reward for his part in the conquest, and reconquest, of New Mexico. The residence was built to be a fortress, with the stables behind it and a walled garden running nearly two blocks long. There was once a secret subterranean passage that had led to the Governor’s Palace. Legend had it that the scalps of Indians had once hung on the weathered vigas outside, proudly displayed by the Spanish settlers who paid a bounty for every head. Nevertheless, Dorothy suspected the office was selected less for its historic value than for its location. While it was just steps away from the main Plaza, the building was somewhat inconspicuous, set back behind a long, narrow courtyard and a shaded grass patio. A heavy, wrought-iron gate at the entrance of the cobblestone passageway discouraged the curious from wandering in. For security reasons, the project’s presence was unobtrusively marked by a small blue sign with red lettering:

U.S. ENG-

RS

The wooden placard was so short that the abbreviated form of “Engineers” had apparently not fit on the first line, so the remaining “rs” rather incongruously occupied the line below. If obfuscation was the army’s main purpose, Dorothy thought the sign succeeded admirably—she had almost walked right by it. In the coming months, she was often reminded of her first impression of the secret headquarters, as dozens of the worlds top scientists failed to notice the tiny sign and passed by the centuries-old courtyard without stopping, blundering around the Plaza for hours in search of the designated contact point where they were to receive their marching orders.