(11/20) Farther Afield (9 page)

Read (11/20) Farther Afield Online

Authors: Miss Read

Tags: #Pastoral Fiction, #Crete (Greece), #Country Life - England, #General, #Literary, #Country Life, #England, #Fiction, #Villages - England

We soon realised how mountainous Crete is. The main ridge of mountains runs along the central spine of the island, but the coast road too boasted some alarming ascents and descents. Part of our journey was along a newly built road, but there was still much to be done, and we followed the path used by generations of travellers from Heraklion to Aghios Nikolaos for most of the way.

The last part of the journey took place in darkness. The headlights lit up the white villages through which we either hurtled down or laboured up. Occasionally, we saw a tethered goat cropping busily beneath the brilliant stars, or a pony clopping along at the side of the road, its rider muffled in a rough cloak.

Every now and again the coach shuddered to a halt, and a few passengers descended, laden with luggage, to find their hotel.

'I wouldn't mind betting,' said Amy, with a yawn, 'that we are the last to be put down.'

She would have lost her bet, but only just, for we were the penultimate group to be dropped. Two middle-aged couples, and a family of five struggled from the coach with us and we made our way through a courtyard to the doorway.

We were all stiff and tired for we had been travelling since morning. A delicious aroma was floating about the entrance hall. It was as welcome as the smiles of the men behind the desk.

'Grub!' sighed one of our fellow-travellers longingly.

He echoed the feelings of us all.

School teachers do not usually stay in expensive hotels, so that I was all the more impressed with the beauty and efficiency of the one we now inhabited.

The gardens were extensive and followed the curve of the bay. Evergreen trees and flowering shrubs scented the air, lilies and cannas and orange blossom adding their perfume. And everywhere water trickled, irrigating the thirsty ground, and adding its own rustling music to that of the sea which splashed only a few yards from our door.

Amy and I shared a little whitewashed stone house, comprising one large room with two beds and some simple wooden furniture, a bathroom and a spacious verandah where we had breakfast each morning. The rest of the meals were taken in the main part of the hotel to which we walked along brick paths, sniffing so rapturously at all the plants that Amy said I looked like Ferdinand the bull.

'Heavens! That dates us,' I said. 'I haven't thought of Ferdinand for about thirty years!'

'Must be more than that,' said Amy. 'It was before the war. Isn't it strange how one's life is divided into before and after wars? I used to get so mad with my parents telling me about all the wonderful things they could buy for two and eleven-three before 1914 that I swore I would never do the same thing, but I do. I heard myself telling Vanessa, only the other day, what a hard-wearing winter coat I had bought for thirty shillings

before the war.

She didn't seem to believe me, I must say.'

'It's at times like Christmas that I hark back,' I confessed. 'I used to reckon to buy eight presents for college friends for a pound. Dash it all, you could get a silk scarf or a real leather purse for half a crown in those days.'

'And a swansdown powder puff sewn into a beautiful square of crêpe-de-chine,' sighed Amy. 'Ah, well! No good living in the past. I must say the present suits me very well. Do you think I'm burning?'

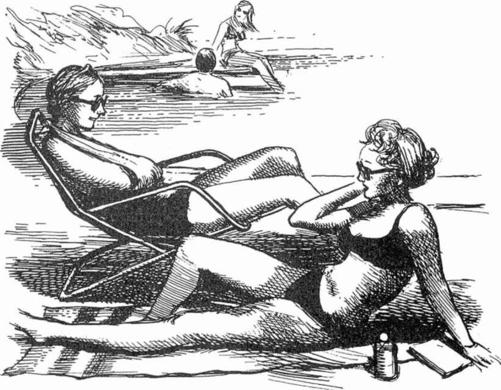

We were lying by the swimming pool after breakfast. Already the sun was hot. By eleven it would be too hot to sunbathe, and we should find a shady place under the trees or on our own verandah, listening to the lazy splashing of the waves on the rocks.

On the terrace above us four gardeners were tending two minute patches of coarse grass. A sprinkler played upon these tiny lawns for most of the day. Sometimes an old-fashioned lawn-mower would be run over them, with infinite care. The love which was lavished upon these two shaggy patches should have produced something as splendidly elegant as the lawns at the Backs in Cambridge, one felt, but to Cretan eyes, no doubt, the result was as satisfying.

For the first two or three days we were content to loll in the sun, to bathe in the hotel pool, and to potter about the enchanting town of Aghios Nikolaos. We were both tired. My arm was still in a sling for most of the time, and pained me occasionally if I moved it at an awkward angle. Amy's troubles were far harder to bear, and I marvelled at her courage in thrusting them out of sight. We were both anxious that the other should benefit from the holiday, and as we both liked the same things we were in perfect accord.

'We'll hire a car,' Amy said, 'for the rest of the holiday. There are so many lovely things to see. First trip to Knossos, and I think we'll make an early start on that day. It was hot enough there when I went in April. Heaven knows what it will be like in August!'

Meanwhile, we slept and ate and bathed and read, glorying in the sunshine, the shimmering heat, the blue, blue sea and the sheer joy of being somewhere different.

Now and again I felt a pang of remorse as I thought of Tibby in her hygienic surroundings at the super-kennels to which I had taken her. No doubt she loathed the comfortable bed provided, the dried cat-food, the fresh water, and the concrete run thoughtfully washed out daily with weak disinfectant by her kind warders.

Where, she would be wondering, is the garden, and my lilac tree scratching post? Where is the grass I like to eat, and my comfortably dirty blanket, and the dishes of warm food put down by a doting owner?

It would not do Tibby any harm, I told myself, to have a little discipline for two weeks. She would appreciate her home comforts all the more keenly when we were reunited.

Our fellow guests seemed a respectable collection of folk. In the main, they were middle-aged, and enjoying themselves in much the same way as Amy and I were. There were one or two families with older children, but no babies to be seen. I assumed that there were a number of reasons for this lack of youth.

The hotel was expensive, and to take two or three children there for a fortnight or so would be beyond most families' purses. The natural bathing facilities were not ideal for youngsters. The coast was rocky, the beaches small and often shelving abruptly. The flight from England was fairly lengthy, and it was easy to see why there were very few small children about.

It suited me. I like children well enough, otherwise I should not be teaching, but enough is enough, and part of the pleasure of this particular holiday was the company of adults only.

We looked forward to a short time in the bar after dinner, talking to other guests and sometimes watching the Greek waiters who had been persuaded to dance. We loved the gravity of these local dances as, arms resting on each others' shoulders, the young men swooped in unison, legs swinging backwards and forwards, their dark faces solemn with concentration, until, at last, they would finish with a neat acrobatic leap to face the other way, and their smiles would acknowledge our applause.

One of the middle-aged couples who had made the journey with us, often came to sit with us in the bar. Their stone house was near our own, and we often found ourselves walking to dinner together through the scented darkness.

She was small and neat, with prematurely white silky hair, worn in soft curls. Blue-eyed and fair-skinned she must have been enchanting as a girl, and even now, in middle-age, her elegance was outstanding. She dressed in white or blue, accentuating the colour of her hair and eyes, and wore a brooch and bracelet of sapphires and pearls which even I coveted.

Her husband looked much younger, with a shock of crisp dark hair, a slim bronzed figure, and a ready flow of conversation. We found them very good company.

'The Clarks,' Amy said to me one evening, as we dressed for dinner, 'remind me of the advertisement for pep pills. You know: "Where do they get their energy?" They seem so wonderfully in tune too. I must say, it turns the knife in the wound at times,' she added, with a tight smile.

'Well, they're not likely to parade any secret clashes before other people staying here,' I pointed out reasonably.

'True enough,' agreed Amy. 'Half the fun of hotel life is speculating about one's neighbours. What do you think of the two who bill and coo at the table on our left?'

'Embarrassing,' I said emphatically. 'Must have been married for years, and still stroking hands while they wait for their soup. Talk about washing one's clean linen in public!'

'They may have been married for years,' said Amy, in what I have come to recognise as her worldly-woman voice, 'but was it to each other?'

'Miaow!' I intoned.

Amy laughed.

'You trail the innocence of Fairacre wherever you go,' she teased. 'And not a bad thing either.'

It was the morning after this conversation that I found myself dozing alone, frying nicely, under some trees near the pool. Amy was writing cards on the verandah, and was to join me later.

I heard footsteps approach, and opened my eyes to see Mrs Clark smiling at me.

'Can I share the shade?'

'Of course.' I shifted along obligingly, and Mrs Clark spread a rug and cushion, and arranged herself elegantly upon them.

'John's in the pool, but it does mess up one's hair so, that I thought I'd miss my dip today. How is your arm?'

I assured her that I was mending fast.

'It's all this lovely fresh air and sunshine,' she said. 'It's a heavenly climate. My husband would like to live here.'

'I can understand it.'

'So can I. He has more reason than most to like the Greek way of life. His grandmother was a Greek. She lived a few miles south of Athens, and John spent a number of holidays with her as a schoolboy.'

'Lucky fellow!'

'I suppose so.' She sounded sad, and I wondered what lay behind this disclosure.

'We visited her, as often as we could manage it, right up to her death about five or six years ago. A wonderful old lady. She had been a widow for years. In fact, I never met John's grandfather. He died when John was still at Marlborough.'

She sat up and anointed one slim leg with sun tan lotion. Her expression was serious, as she worked away. I began to suspect, with some misgiving, that once again I was destined to hear someone's troubles.

'You see,' she went on, 'John retires from the Army next year, and he is set on coming here to live. He's even started house-hunting.'

'And what do you feel about it?'

She turned a defiant blue gaze upon me.

'I'm dead against it. I'm moving heaven and earth to try to get him to change his mind, and I intend to succeed. It's a dream he has lived with for years – first it was to live in Athens. Then in one or other of the Greek islands, and now it's definitely whittled down to Crete. I've never seen him so ruthless.'

I thought of Amy who had used almost exactly the same words about James.

'Perhaps something will occur to make him change his mind,' I suggested.

'Never! He's thought of this kind of life wherever he's been, and I feel that he's been through so much that it is right in a way for him to have what he wants, now that he will have the leisure to enjoy it. But the thing is, I can't bear the thought of it. We should have to leave everything behind that we love, I tell him.'

She began to attack the other leg with ferocity.

'We live in Surrey. Over the years we saved enough to buy this rather nice house, with a big garden, and we've been lucky enough to live in it for the past seven years. Before that, of course, we were posted here, there, and everywhere, but one expects that. I thought that John had given up the idea of settling out here. He's seemed so happy helping me in the garden, and making improvements to the house. Now I realise that he was looking upon the place as something valuable to sell to finance a home here. And the garden – ,'

She broke off, and bent low, ostensibly to examine her leg.

'Tell me about it,' I said.

'I've made a heavenly rockery. It slopes steeply, and you can get some very good terraces cut into the side of the hill. My gentians are doing so well, and lots of little Alpines. And three years ago I planted an autumn flowering prunus which had lots of blossom last October – so pretty. I simply

won't

leave it!'

'You could make a garden here I expect. My friend Amy tells me that when she was here last, in April, there were carnations and geraniums, and lilies of all sorts. Think of that!'

'And then there are the grandchildren,' she went on, as though she had not heard me. 'We have two girls, both married, who live quite near us, and we see the grandchildren several times a week. There are three, and a new baby due soon after we return. I'm going to keep house for Irene when she goes into hospital, and look after her husband and Bruce, the first boy.'

'You'll enjoy that, I expect,' I said, hoping to wean her from her unhappiness. I did not succeed.

'But just think of all those little things growing up miles away from us! Think of the fun we're going to miss, seeing them at all the different stages! I keep reminding John of this. And then there's Podge.'

'Podge?'

'Our spaniel. He's nearly twelve and far too old to settle overseas, in a hot climate. Irene has offered to have him, but he would grieve without us, and I should grieve too, I don't deny. No, it can't be done.'