1415: Henry V's Year of Glory (90 page)

Read 1415: Henry V's Year of Glory Online

Authors: Ian Mortimer

Calais, from a drawing of 1535–50. Henry’s numerous preparations for provisioning the town in early 1415 suggest that the embarkation of the army here was planned from the outset.

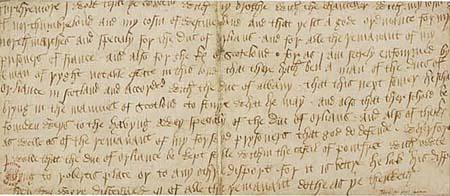

This letter from Henry, concerning the duke of Orléans and the security of the north of England, is widely believed to be in the king’s own hand.

Notes

Prologue

1.

McFarlane,

Lancastrian Kings

, p. 133. It is worth noting that McFarlane did not specify what he meant by ‘greatness’ or ‘the greatest man’.

2.

McFarlane wrote ‘the historian cannot honestly write biographical history: his province is rather the growth of social organisations, of civilisation, of ideas’ (quoted in Harriss,

Cardinal Beaufort

, v).

Introduction

1.

Vaughan,

John the Fearless

, pp. 44–8.

2.

Vaughan,

John the Fearless

, pp. 71–2.

3.

Vaughan,

John the Fearless

, p. 85. The guidebook to

La tour Jean sans Peur

, Paris, suggests that it was not actually the duke’s bedchamber. The reasons it gives are that the tower is small, and not of the expected ducal grandeur. The chamber beneath the duke’s is described today as the equerry’s chamber. However, Vaughan’s statement, based on the building accounts, is explicit: the principal room was indeed designed for John’s personal safety at night. The fifteenth-century chronicler Monstrelet also states specifically that he built this tower to sleep in at night. The two chambers are supported on huge stone pillars, rising twenty-five feet or so above the first-floor guard chamber, and reached only by an extremely elaborately carved stone staircase, which incorporates several of the duke’s heraldic badges. The wonderful staircase ceiling suggests strongly that, although this was a small chamber, it was intended to be seen by the duke. The whole edifice amounted to a lordly stone box supported sixty feet above the walls of Paris. And as the tower was constructed in 1408–9, after the murder of Orléans and John’s return to the city, I suspect that the extraordinary design, incorporating so much empty space, was a means of preventing the duke being attacked in his bedchamber by the use of fire. The tower is illustrated in the second

plate section of this book.

4.

Allmand,

Henry V

, p. 48. There had been earlier embassies appointed to negotiate with Burgundian ambassadors – e.g. those of 3 July 1406 and 29 November 1410 (Hardy,

Syllabus

, pp. 556, 566) but these seem to have been for the defence of Calais and the local truce. See Nicolas (ed.),

Privy Council

, ii, pp. 5–6 for the instructions to the ambassadors appointed on 29 November 1410.

5.

Fears

, esp. p. 322.

6.

Fears

, p. 337; Allmand,

Henry V

, p. 48.

7.

Monstrelet

, i, pp. 18–19. Although the then duke of Burgundy (Philip the Bold) was excepted by Louis in this agreement, this was only with regard to Louis’ part of the bargain. In other words, Henry would have still been liable to help Louis against John the Fearless’s father even though Louis was not bound to help Henry against the duke of Burgundy.

8.

Fears

, pp. 114, 134–5, 155.

9.

Hardy,

Syllabus

, ii, pp. 567–8. An extension of the truce in Flanders was sealed on 27 May 1411.

10.

In support of this it should be noted that on the same day that Henry appointed the ambassadors to treat with the Burgundians at Calais he granted safe conduct for ambassadors of the king of France to come to England. See

Syllabus

, ii, p. 566. See also p. 567, where redress of injuries with ambassadors from Burgundy and France are simultaneously authorised on 27 March 1411.

11.

Curry,

Agincourt

, p. 26.

12.

Fears

, p. 339; Nicolas (ed.),

Privy Council

, ii, pp. 19–24.

13.

Given-Wilson (ed.),

PROME

, 1411 November (Introduction) states the fleet sailed in September. Curry,

Agincourt

, p. 27, states that the force was sent to meet the duke of Burgundy at Arras on 3 October.

14.

Allmand,

Henry V

, pp. 48–9. It is perhaps significant that the name of the duke of Berry was removed from the 1 September instructions to the ambassadors to treat with John the Fearless, removing any requirement for the English to fight Berry on John’s behalf. See Nicolas (ed.),

Privy Council

, ii, pp. 21–4.

15.

Fears

, p. 338. The consensus view on intervention in France in 1411 is specified in Allmand,

Henry V

, p. 48; Curry,

Agincourt

, p. 27.

16.

In

Fears

, p. 341, I stated two thousand English archers and eight hundred men-at-arms were at St-Cloud. However, recent research suggests that the expedition consisted of just one thousand men (200 men-at-arms and 800 archers). See Tuck, ‘The Earl of Arundel’s Expedition’, p. 232. See Curry,

Agincourt

, p. 29 for further variations on the number.

17.

Fears

, p. 345.

18.

Hingeston (ed.),

Royal and Historical Letters

, ii, pp. 322–5; Curry,

Agincourt

, p. 31.

19.

Fears

, p. 347. They were built at Ratcliffe in the Thames, according to Wylie,

Henry V

, ii, p. 372.

Christmas Day 1414

1.

I have presumed that Henry held his Christmas feast in 1415 in Westminster Hall, where the marble seat stood. It is entirely possible that he held it instead

on a smaller scale, in the White (or Lesser) Hall, to the south. However, as Christmas was one of the three traditional crown-wearing occasions, and given Henry’s attitude to traditional kingship, I suspect that Westminster Hall was the actual venue.

2.

For Christmas rituals in the medieval royal household, see Hutton,

Rise and Fall

, chapter one.

3.

The problem is dealt with in full in Mortimer, ‘Richard II and the Succession’;

Fears

, Appendix Two. A simplified overview appears in Mortimer, ‘Who was the rightful king in 1460?’

4.

Fears

, pp. 190–1.

5.

The spice-plate is mentioned in Henry’s inventory. See

PROME

, 1423 October, item 31 (the inventory of Henry V), entry no. 8. It is described as ‘the great gold spice-plate, set with a balas ruby in the mouth of the eagle on the fruitlet of the said spice-plate’. It had twelve balas rubies and sapphires around the fruitlet, six pearls and four pendant pearls in the beaks of four eagles, and 229 pearls and twenty-four balas rubies and sapphires around the cover. It also had twenty-four clusters, each of four pearls and a diamond, around it, and an eagle with a sapphire in its beak in the bottom of the basin of the spice-plate. Around each of the feet were four large pearls, four balas rubies, four sapphires and 112 pearls. The whole object was worth £602 5s.

6.

This impression of ‘innocence’ is not a contemporary description but my own impression, based on studying the English portrait of Henry in the Royal Collections.

7.

Hutchinson,

Henry V

, p. 72; McFarlane,

Lancastrian Kings

, p. 124.

8.

Woolgar,

Senses

, p. 138.

9.

For the slashed sleeves, see the portrait of Henry V in the Royal Collection; for Henry wearing a high-collar gown, see the image of Hoccleve presenting his

The Regement of Princes

to Henry (BL Arundel MS 38, fol. 37); for long sleeves with rich linings see the same image and also the image of Jean de Galopes presenting his translation of Bonaventura’s

Life of Christ

to Henry (Corpus Christi College, Cambridge, MS 213 fol. 1r.). For a

hanseline

worth £151 belonging to the king, see Henry’s inventory in

PROME

, 1423 October.

10.

Wylie,

Henry V

, i, p. 191.

11.

Wylie,

Henry V

, i, p. 190.

12.

Wylie,

Henry V

, i, pp. 200–1. Both the earl of Ormonde and Bishop Courtenay attested to this separately.

13.

Wylie,

Henry V

, i, p. 195.

14.

Wylie,

Henry V

, i, p. 201.

15.

Wylie,

Henry V

, i, p. 188.

16.

Barker,

Agincourt

, p. 39. For the exhortation to look the lord directly in the face as a matter of good manners, see Furnival (ed.),

Babees Book

, p. 3.

17.

Although he did empower negotiators to treat with the king of Aragon and the duke of Burgundy for his marriage to their daughters, these seem not to have been serious offers, as the Aragon negotiators were men of relatively low rank. The marriage to the duke of Burgundy’s daughter was negotiated while Henry was still prince; the marriage negotiated when he was king was to Katherine of France.

18.

His promises to consider no other marriage but to Katherine are in

Foedera

, ix, p. 140 (18 June 1414), p. 166 (18 October 1414), pp. 182–4 (4 December, extending promise to 2 February 1415).

19.

Writing by the king survives in

all three languages. It is not proven that he spoke Latin, but it is probable, given that he chose to write in it. According to Allmand in

ODNB

, Henry V could speak Latin.

20.

Allmand states in

ODNB

that the fifteenth-century story of his residing at Oxford under Beaufort’s care in 1398 is unsupported.

21.

‘No one expected him to become king’, wrote Professor Allmand in his

Henry V

(1992), p. 8. Since that work was written, Edward III’s entailment to the throne, made in 1376, has been brought to light by Professor Bennett. This makes clear that Henry IV believed rightly that he was likely to succeed to Richard II’s throne if Richard should die without children. By September 1386 Richard had been married for over four years and his wife had not conceived. With regard to Henry V’s date of birth on 16 September 1386, see Mortimer, ‘Henry IV’s date of birth and the royal Maundy’, pp. 568–9, n.7. By the time Henry V was six, Richard II had been married for more than ten years without progeny. There was therefore every reason to suspect that Henry IV would indeed inherit the throne, in line with Edward III’s entail; and, if not Henry IV, then one of his sons, presumably the eldest, Henry V. Therefore his father and grandfather – at the very least – expected him to inherit.

22.

For example, Henry IV executed the archbishop of York in 1405 as well as other prelates in later years. Henry V was in opposition to the archbishop of Canterbury in religious and political affairs in the last years of Henry IV’s reign.

23.

For Henry’s devotion to the Trinity and to the English saints, see Allmand,

Henry V

, pp. 180–1. For Edward III’s devotion to the English saints, see

Perfect King

, p. 60. For Edward III’s devotion to the Virgin Mary, see

Perfect King

, pp. 111–12. For Henry IV’s devotion to the Trinity, see

Fears

, pp. 196–7.