1636: Seas of Fortune (35 page)

Read 1636: Seas of Fortune Online

Authors: Iver P. Cooper

Tags: #Fiction, #Science Fiction, #General, #Alternative History, #Action & Adventure

That was in Hideyoshi’s edict in the fifteenth year of Tensho, Sadamitsu recalled. 1587 in the Christian reckoning. Why was the shogunate wasting his time with this?

“2. They also spread a pernicious doctrine to confuse the right ones, with the secret intent of changing the government of the country and giving ownership of the country to a European king.”

Well, that hadn’t been in an edict, but the apostate’s oath required that he admit that the purpose of the padres’ teachings was to justify and facilitate taking the lands of others.

“3. However, we know from the example of the Dutch that it is possible to be Christian without acting outrageously.”

Sadamitsu didn’t like where this was going.

“4. Hence, the Japanese-born followers of the padres will be allowed to worship according to their conscience, and Japanese-born padres and brothers will be permitted to teach the Christian faith, but only in duly constituted Christian settlements in New Nippon, a land across the sea.”

Exile! What was the shogun thinking? It was true that exile, whether from Edo, or one’s home province, or to some desolate island, was a time-honored punishment in Japan, but if the

kirishitan

were sent into exile, wouldn’t they just sneak back?

And where was this New Nippon? North of Korea, perhaps? Across the Sea of Okhotsk? Well, at least they would freeze their butts off.

The prisoners were praising their Lord, now. How irritating.

“Keep reading,” said the messenger. Was he smirking? It wasn’t as though

his

job was at risk!

“5. In order to be permitted to go to New Nippon, they must take oath, on pain of eternal punishment by the Father, Son and Holy Ghost, as well as by Saint Mary and all Angels and Saints, as follows:

“a) they will not return to the homeland without permission of the shogun, or assist any Southern Barbarian in going to the homeland without permission of the shogun.

“b) they will defend New Nippon against the Christian powers, obey the daimyos duly appointed by the shogun to govern them, and support their daimyos as is customary, save as they may be excused during the first years of settlement.

“c) they will not oppress the worshipers of the buddhas and kamis, or the followers of Confucius, in that land, or prevent any Christian from renouncing that faith and returning to any of the traditional religions of Nippon.

“d) they will repay the cost of their transportation to New Nippon as soon as is reasonable.

“e) they will provide the inquisitors with any information they have as to the whereabouts of Christians still in hiding.”

Sadamitsu turned to the messenger. “How are we going to enforce this oath?”

He shrugged. “They will be shipped in batches. Those still in Japan will be punished if the first to be sent are disobedient. And they will need supplies shipped to them if they are to survive, let alone prosper. Gunpowder, if nothing else.”

“Still—”

“Please, finish reading the edict.”

Sadamitsu took a deep breath.

“6. Those who timely accept exile, and cooperate with the authorities, will be permitted to take all of their possessions to New Nippon. Those who do not, will forfeit, depending on the circumstances, some or all of their possessions before being sent into exile, and will be required to work as servants, for an appropriate period of years, for those who behaved properly.”

Oh, I like that, Sadamitsu thought. Create a schism in the Christian community between those who surrendered quickly and those who tried to stay in hiding, with the ones we prefer on top.

“7. Any informer revealing the whereabouts of followers of padres that have not timely surrendered themselves must be rewarded accordingly. If anyone reveals the whereabouts of a high ranking padre, he must be given one hundred pieces of silver. For those of lower ranks, depending on the deed, the reward must be set accordingly.”

Sadamitsu thought about this for a moment. Perhaps he would go into the padre-hunting business, now that he couldn’t execute them.

“8. Any apprehended padres who are Southern Barbarians shall stand surety with their lives for the good behavior of the followers permitted to go to New Nippon. If all goes well, then in twelve years they will be permitted to pay for their transport to a Southern Barbarian land. Any who afterward return will be executed in the most painful way imaginable.”

Good, good. Sadamitsu prided himself on his imagination.

“9. Any Japanese-born followers of the padres who fail to take the oath, or to apostasize, within three years of this edict, are to be executed.

“10. Books teaching the Christian faith may be taken or sent to New Nippon, but only if they are in the Japanese language, are offered for inspection by the inquisitors, and are found to not contain teachings contrary to the required oath.”

The edict closed with the formulaic,

“You are hereby required to act in accordance with the provisions set above. It is so ordered.”

Sadamitsu looked at the Christian captives. “So, do you wish to take the oath?” They nodded their heads.

“Don’t be hasty,” he admonished. “New Nippon is probably thousands of

ri

away, too cold in the winter and too hot in the summer, filled with savage monsters eager to dine on

kirishitan

flesh.”

They assured him that they would prefer to take their chances with the monsters.

Nagasaki, Japan

“Can it really be true?” Mizuki asked her husband. “That if we go on these ships, that we will be taken to a land where we will be free to worship the Christ?”

“That’s what the proclamation said,” Takuma admitted. “But it might be a trick, to get us to reveal ourselves. Then they kill us. Or perhaps they will let us board the ships, but then, once we are out of sight of land, throw us overboard.”

“How long do you think we will live if we stay here? There are spies everywhere,” said Mizuki. “And what of our son? You know how precocious he is. He has learned his catechisms so well. But that makes it all the harder for him to carry about the pretense that he is Buddhist. What will happen at next year’s efumi? Will he refuse to desecrate the images?”

“Oto-sama, what do you think?” Takuma was addressing his father, who had retired as head of the household a decade earlier, but of course was still consulted on all major decisions.

“If you don’t throw the dice you’ll never land sixes.”

* * *

“So, soon we will leave for New Nippon,” said Mizuki.

“Indeed,” said Takuma as he packed his wares. “More precisely, we will be helping to

create

New Nippon. Right now, it’s just a wild land, according to the Red-Hair merchants I have done business with. The Red-Hairs call it—” he struggled visibly to recall the strange Dutch word—“America.”

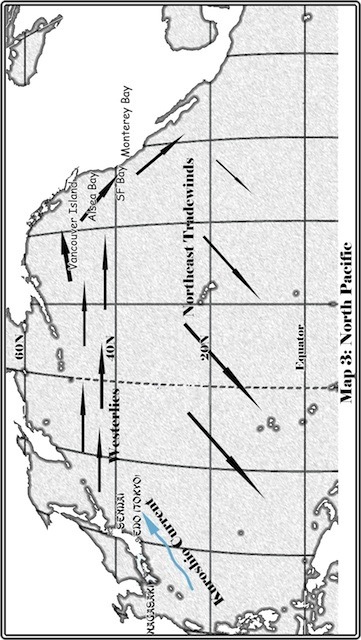

Map 3: North Pacific

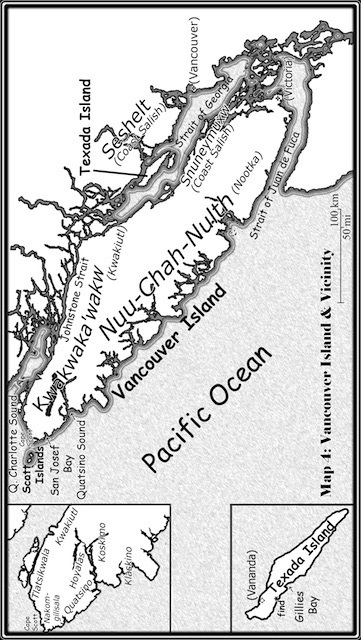

Map 4: Vancouver Island and Vicinity

Fallen Leaves

February 1634 to August 1634

If a west wind blows,

They pile up in the east—

The Fallen Leaves.

—Taniguchi Buson (1715–83)

2

February 1634,

Osaka Castle

“Isn’t it marvelous? I have the old plotter just where I want him.” With a sudden movement, Tokugawa Iemitsu, shogun of Japan, snapped his fan closed and then open again, as if driving off flies.

His tairo and chief councillor, Sakai Tadakatsu, smiled thinly. “Forgive me, Great Lord, but Nippon is not merely the Land of a Thousand Kami, it is the Land of a Thousand Old Plotters.” The shogun snorted in agreement, and Tadakatsu continued, “Which particular old plotter do you have in mind?”

“Date Masamune.”

“Ah.”

Iemitsu paused for a moment, admiring the play of light on the Tokugawa mon, three encircled hollyhock leaves, set out in gold leaf on one side of the fan. “He perplexes me. In the barbarian year 1614, he dared to send an embassy to the king of Spain, without my father’s permission. The act was proof that his ambition to be shogun was not dead. But in 1632, when my father was near death, and publicly voiced his fear that I was too young to prevent the return of civil war, Masamune declared before the assembled daimyo that he would defend my right to rule.”

“Perhaps his ambitions mellowed with age.”

“Perhaps. But who knows what long-banked fires have awakened, thanks to the tidings of Grantville? I have no doubt of his sagacity, but I would prefer it to be exercised across the Great Ocean. Hence, I put him in a position where he couldn’t reasonably refuse the appointment.”

“You think of this as if you are playing a game of Go with him, and have found a

kikashi

.” That was a forcing move. “But perhaps you are really playing

kemari

.” That was the courtiers’ kickball, a cooperative game, played in Japan for a millennium. The players had to keep the ball in the air, each giving it a few kicks before passing it to the next one.

Iemitsu gave his back a quick scratch with the folded fan. “How so?”

“You need someone who can keep the

kirishitan

under a firm hand, yet is respected by them. And Date Masamune . . . he is an old warrior in a land at peace. Perhaps his dream is to die on horseback in the middle of a battle. In New Nippon, fighting the Indians or the Spanish, perhaps he will do so. So this appointment may be to the benefit of both of you.”

Spring 1634,

Kirishitan Internment Camp,

Hashima Island, outside Nagasaki, Japan

Doctor Zhang knelt in front of young Hiraku, the Yamaguchis’ only child. Hiraku was already kneeling. He was also trembling.

His mother, Mizuki, kissed his head. His father, Takuma, frowned, but didn’t rebuke Mizuki for coddling Hiraku.

Zhang very carefully took a vial out of a pouch wrapped against his skin, and set it on the floor. Then he reached into his bag and pulled out a two-foot-long silver tube, slightly curved at one end. He ground the curved end of this inside the vial, and held the straight end by his mouth.

“Tilt your head back, boy,” said Zhang. “More, more, look at the ceiling. That’s good. Hold it right there.”

He carefully inserted the curved end of the tube into Hiraku’s right nostril. “This won’t hurt a bit.” Zhang blew the dried pox material into the boy’s nose.

“There, like sneezing in reverse, eh?” he said to Hiraku.

Zhang turned to face the parents, and they bowed to him. “Remember, he may only be visited by those who have already had the ‘heaven flowers.’” That was the Chinese euphemism for smallpox. “In six or seven days he will have a fever, and you may treat him with the herbs I gave you. The eruption will occur a few days later. Scabs should form after two weeks. I will return then, so I can collect the material. The scabs should fall off after another week or so, and he can then live a normal life.”

“We have prayed that it will be so.”

Zhang sniffed. “To your Christian God?” They nodded.

“And to Mary, the Mother of God,” Mizuki added.

“Well, I hope that’s sufficient. I still think you should have let me conduct the normal ritual.” That involved praying to the Goddess of Smallpox, who in turn was an incarnation of the Goddess of Mercy.

Zhang was a Chinese practitioner, from a medical family, who had come to Japan a few months earlier. A chance encounter with a

bakufu

official had led to him being questioned about his methods of preventing smallpox. Zhang claimed that dried and aged scabs, mixed with appropriate medicinal herbs, and warmed in his armpit pouch for a month, were efficacious.

He assured the official that if, on a lucky day according to the calendar, the preparation was blown into the nostril of a child (right for a boy, left for a girl), it provided immunity against the dread disease. Asked about survival rates, he asserted not even one in a hundred failed to recover from the treatment.

The

bakufu

official was impressed, and suggested to his superiors that perhaps condemned criminals might be allowed to volunteer, their lives spared if they survived the immunization. The suggestion made its way up the chain of command, and one of the junior councillors of the shogun had the bright idea, why not test Zhang’s methods out on the

kirishitan

instead? If they were successful, they could be adopted more generally. If they caused smallpox, well, then there were a few less Christians to worry about.

The first uses of Zhang’s

han miao fa

were limited by the supplies that Zhang had brought with him, but of course each patient became the source of fresh material.

Hiraku was one of Zhang’s first

kirishitan

patients; his parents had lost their first two children to smallpox. Their prayers were answered; Hiraku survived the immunization.

* * *

After several hundred were treated successfully, the

bakufu

invited Zhang to Edo, to treat selected members of the shogun’s household.

Date Masamune’s agents had quietly monitored Zhang’s experiment. After Zhang left, Masamune’s own physicians continued the immunizations, among the Christians as well as the people of Rikuzen, as they had been instructed by Zhang.

Some Christians objected to Zhang’s rituals, others permitted it, figuring that as long as it was Zhang praying, not them, they were committing no sin. And of course, in the shogun’s household, only the Buddhist ritual was practiced.

This came to Masamune’s attention, and he questioned his doctors as to whether it made a difference who was prayed to. “It didn’t appear to,” he was informed.

His reaction was just one word. “Interesting.”

May 1634,

Sendai Castle (Date Clan Family Home)

Captain Abel Janszoon Tasman of the Dutch East India Company earnestly hoped that this would not be a long meeting. He had not been in Japan long enough to feel at all comfortable squatting for hours. He tried as best he could to copy how the Japanese captain sitting beside him had locked his heels under his buttocks, but feared that his imitation was poor.

A flunky announced the coming of the great lord, bellowing “All kow-tow for Date Masamune-sama, Echizen no Kami, Mutsu no Kami, Daimyo of Rikuzen, Taishu of New Nippon.”

Taishu

meant “grand governor,” and was, according to Tasman’s colleagues, the local equivalent of a Viceroy.

Of course, the title by which Date Masamune was best known was

dokuganryu

—“one-eyed dragon.” This was a reference to the loss of his right eye. According to Tasman’s sources, Masamune had gone blind in that eye as a result of childhood smallpox. It was a common enough consequence of the disease. What wasn’t so common was Masamune’s reaction; Tasman had been told that Masamune had plucked it out so that an enemy couldn’t take advantage of it in battle.

And he was in battle frequently enough. The shadow of his famous helmet, bearing a crescent moon, had fallen on scores of battlefields. And he was a successful general, serving first Hideyoshi in Korea, and then Ieyasu when he unified Japan.

Perhaps too successful. He was one of the most powerful daimyo in Japan, and the Tokugawa had suspected that he had ambitions to become something more than a mere daimyo . . . a shogun. They were particularly irritated when he sent his own embassy to the pope in faraway Rome. Still, they had grudgingly found him to be indispensable.

Tasman’s superiors were certain that Shogun Iemitsu had been ecstatically happy when he realized that he could give Masamune a position of immense prestige . . . thousands of miles away.

Masamune addressed the Dutch captain in slow but understandable Portuguese. “Please explain.”

“Explain what, milord?”

“The proposed sailing route. Look!” Masamune pointed to the globe that his aide had reverently placed in front of him. It was a duplicate, as near as skilled Japanese craftsmen could make it, of the “Replogle” globe presented to the shogun the previous summer.

“This is the world according to the wizards of Grantville that your people spoke of. Now look.” He held a string taut across the surface from Sendai, the capital of his

han

, to Monterey, California, then released it. “This is the shortest path, neh?”

Tasman nodded. “That’s true, milord. But it’s not a route we can easily sail.”

“No? But the globe shows that the currents are favorable. See—Masamune’s finger traced out a chain of dashed blue arrows on the globe—this is marked, ‘Kuroshio Current.’ ‘Kuroshio’ is Japanese, meaning ‘Black Stream.’ Our sailors know it well, it is very fast and very dark. The short route should also be a fast route.”

“May I touch it, please?”

Masamune swept his hand in a graceful arc from Tasman to the globe.

“There are two problems, milord. Here is the North Pole, at ninety degrees north latitude, and this is the equator, at zero degrees. These smaller circles are the lines of latitude. Sendai is at about thirty-eight, and the up-timers’ Monterey a little farther south. Now, may I have that string, please?” Masamune silently handed it over.

Tasman laid it down between Sendai and Monterey. “See how close it comes at the middle of the journey to the fifty-degree line? It will be very cold there.”

“Even in summer?”

“Even then. There are likely to be more storms, that far north. And there could be icebergs.” When Masamune failed to react, Tasman quickly explained, “great masses of ice, some larger than ships, that float in the water. Most of the ice is below the water, and can’t be seen. They are very dangerous to shipping.”

The Japanese captain interjected, “Excuse me, Great Lord, but I have heard of such floating ice. Each year, some wash up on the beaches of Hokkaido.” These icebergs in fact came from glaciers calving into the Sea of Okhotsk. The North Pacific was virtually free of icebergs, as those of the Arctic ran aground in the Aleutians, but none of the participants in the meeting knew this.

“And the second problem?”

“Staying on course. We steer by the compass. If we run down a latitude eastward, we just make our way east as best as the winds allow, and we can tell from the height of the sun at noon whether we are too far north or south.

“But if we take this path—and indeed your lordship is most astute to recognize that this is the shortest path—then we start on a northeast heading, and mid-cruise we are heading east, and near Monterey we must bear southeast.

“Alas, since we cannot tell our longitude—” the Dutchman moved his hand back and forth between Japan and North America—“that is, our easting or westing, we would not know when to change the course.”

Masamune stated at Tasman. “Why can’t you tell your longitude?”

“We could if we had a clock that could keep time even at sea. Then we could set the clock to Sendai time before departing.” Tasman turned the globe slowly. “This is how the Earth turns. As it turns, the sun seems to climb in the sky, then sinks. When the sun has reached its highest point in the sky, we call that noon. Noon will come earlier in San Francisco than in Sendai. En route, at noon, we would look at the clock to see what the time in Sendai was, that is, how much before noon. And from that we would know the distance in longitude.”

“And you cannot build such a clock?”

“We can’t. Our clocks use a pendulum to keep time, and the rocking of the boat plays havoc with it.” Tasman shrugged his shoulders. “Perhaps the up-timers can do better.”

Masamune stared at the globe. “They must have, in order to draw these longitude lines, neh? Well, if you can’t build such clocks yet, we can’t either.” The Europeans had brought clocks to Japan.

Tasman didn’t belabor the point, but the clocks made for use in Japan wouldn’t be useful for voyagers even if the waters of the Pacific were as quiet as those in a bathtub. The Japanese didn’t have a standard hour, but rather divided the day and night each into six equal parts, whether the days were summer long or winter short. The customized clocks presented by the Europeans to the shogun and several of the more important daimyos had complicated mechanisms to adjust for the seasonal variation at Edo or Nagasaki in the length of the day.

“So, milord, our route is a bit of a compromise. We head northeast, passing abreast of your northern island—”

“Ezochi,” Masamune interjected.

Tasman inclined his head slightly. “Thank you, Your Grace. The American globe calls it Hokkaido. And then when we are at latitude forty-five degrees, by the sun, even with this island—” he pointed at Iturup, in the Kurile Islands, with his rather grimy fingernail—“we turn east. When we sight the coast of America, we turn south, and this ‘California Current’ will speed us down to the latitude of Monterey.”

Masamune turned to the Japanese captain on his left, and they spoke hurriedly and softly in Japanese. “Captain, please repeat what you just told me.”

“Tasman-sama,” said the Japanese captain, “why do we need to worry about where the sun journeys? We can follow this chain of islands to this peninsula, then cross to this second island chain, and run along this second peninsula, and finally sail down the coast.” The path he outlined was from the Kurile Islands, to Kamchatka, the Aleutian Islands, the Alaska Peninsula, and then along Alaska, British Columbia, and the Pacific Northwest. “According to the distance scale, I think we would always be in sight of land.”