1636: Seas of Fortune (41 page)

Read 1636: Seas of Fortune Online

Authors: Iver P. Cooper

Tags: #Fiction, #Science Fiction, #General, #Alternative History, #Action & Adventure

Isamu was standing next to Yoritaki when Tokubei put the question to the samurai commander, and as soon as Yoritaki gave his assent, Isamu volunteered to lead the little Texada samurai contingent. This might have been out of eagerness to impress Yoritaki, but Tokubei suspected it had something to do with Yells-at-Bears’ involvement. They had been surreptitiously eyeing each other for several days now.

Heishiro’s crewmen were less enthusiastic—they wanted to be repatriated to Japan as quickly as possible—but Tokubei told them bluntly that they should expect to be in California for at least a year, until they had taught Kwak’wala, and any other native language they knew, to selected colonists. After they absorbed this bit of bad news, he assured them that they would undoubtedly be rewarded for each language they passed on. He then spoke to each of them privately, and eventually found the right lure to keep one of them on Texada.

* * *

Tokubei lowered the telescope. They had left Gillies Bay, and Isamu’s party, behind them. The latter had drawn up and secured their boat, and found a path up from the beach. They had quickly passed out of sight, and Tokubei hoped that they would be all right. His report would direct the future colonists to Gillies Bay; it would be easy to find, as at the northern point, there was an unusual white patch, two spots like a pair of plum blossoms. There was nothing like it anywhere else along the western coast of Texada.

* * *

“Tokubei-san.” Yoshitaki had come up behind him.

The mariner started. He hadn’t seen or heard the big samurai’s approach.

“It’s a great thing you’ve begun here,” said Yoshitaki. “The grand governor will certainly reward you.” He paused. “If it were up to me, I’d say you should start thinking about what might be a nice surname for your house.” A surname . . . the sign of samurai status.

Late August 1634,

Oregon Coast

“Where have you been?” demanded Standing-on-Robe, of the Alsea Indians. “You should have been home before the sun stopped climbing the sky!”

His son, Little Otter, was not especially abashed. “I was by the beach, gathering clams, as you told me to, when I saw a white cloud on the horizon.”

“A white cloud? How amazing!” said his older brother.

“Stay out of this,” said Standing-on-Robe.

“The white cloud was moving straight toward me, not with the other clouds. Then it split into many clouds. The clouds came closer together, and I saw that they were hovering over a forest of pine trees, that in turn were planted on the backs of great whales.

“So I ran and hid in the forest. I waited there a few hours, and then circled back here.”

Little Otter was, perhaps, fortunate that his people didn’t believe in corporal punishment of children for lying. Even though he wasn’t.

* * *

The First Fleet had made landfall in Alsea Bay, on the coast of Oregon. Armed parties landed first, to set up a defensive perimeter, and then the passengers were given the chance to come ashore, stand, however unsteadily, on dry land, and to collect fresh water and food.

The Alsea Indians noted the great numbers of the intruders, and decided it was prudent to move upriver. Naturally, they left a few scouts to keep an eye on the Japanese.

One of these was Standing-on-Robe. Little Otter was given strict instructions to stay with his mother. Naturally, he slipped out after the scouts as soon as he saw the opportunity. As he made his way downriver, he saw something truly, truly shocking.

When Standing-on-Robe returned, he found Little Otter telling his friends just how ghastly the visitors were.

“Most of them look like men, but they are ruled by some kind of giant beetle. The beetles had eight legs—”

“Beetles have six legs,” said his older brother. “That’s it.”

“Well, these had eight legs, like a spider, but were armored like a beetle. Anyway, they moved on just four of the legs, but they could run faster than any man. And they had a long sting in front.”

“Oh, you’re just making this up.”

“Am not.”

“You couldn’t have seen it, you were confined to camp.”

“I sneaked out.”

“Wait until I tell Father.”

Standing-on-Robe sent him to bed without supper. But the punishment was for sneaking out, not lying. By then, Standing-on-Robe, too, had seen what a samurai on horseback, carrying a lance, looked like.

* * *

Yamaguchi Takuma placed a white cloth on Munesane’s forehead, and put salt, an ancient symbol of wisdom, in his mouth. Then Yamaguchi picked up the pitcher and began to pour.

Water dripped down Munesane’s eyebrows as Yamaguchi baptized him with the waters of North America. Every

kirishitan

had to know how to administer baptism, but Yamaguchi was a

mizukata

, the elected baptizer of his group of hidden Christians. The honor of baptizing Munesane had first been offered to Imamura Yajiro, but he had declined and suggested Yamaguchi do it instead.

As Yamaguchi poured, he chanted, “I baptize you ‘David,’ in the name of the Father, the Son, and the Holy Ghost. Amen.”

* * *

Yajiro had witnessed many baptisms before, but this one was different. This one, Yajiro knew, could not fail to have an impact on history. Date Munesane—‘David Date,’ Yajiro corrected himself—was the heir apparent to the province of New Nippon. When, as they no doubt would eventually, the Spanish discovered the Japanese settlement in Monterey, they would discover that it was a Christian kingdom. This wouldn’t stop them from attacking it, but it would give them pause. And the delay would allow the Japanese to entrench themselves.

It was because of the political significance of the baptism that he had refused to administer the sacrament. What would happen if his secret—that he was a

bakufu

spy—was revealed? He couldn’t risk undermining the religious foundation of David Date’s legitimacy as a Christian ruler.

Yajiro’s thoughts turned to the conflict between Christianity and Buddhism. Not for the first time, he wondered why Christians were so, so exclusivist, in their teachings. Buddhism, like Christianity, was a foreign religion, and yet it had made its peace with the Shinto priests. The Shinto kami, it judged, were manifestations of the buddhas.

The use of water for ritual purification was hardly unique to Christianity. In the

misogi

ritual, the

shugendo

, the mountain ascetics, would stand under a cold waterfall, before communing with the kami. And the Tendai Buddhists practiced

kanjo

, the sprinkling of water on the head as part of the ordination of a monk.

Yajiro couldn’t help but wonder whether it was possible to reconcile Christanity with Buddhism, even as Buddhism and Shintoism had been reconciled.

* * *

“David Date,” as he would now be known, boarded Yamaguchi’s ship. Since Yamaguchi didn’t have a cabin of his own, the captain lent him his own for the final ceremony. David made confession, and Yamaguchi gave him wheat

mochi

and grape wine. Then he made the sign of the cross on David’s forehead, anointed him with oil, and slapped him on the right cheek. Date Munesane was now a

kirishitan

.

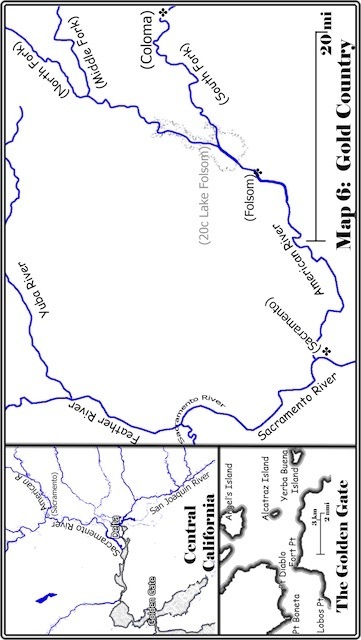

Map 5: SF and Monterey Bays SF

Map 6: Gold Country

Wild Geese

September 1634 to Fall 1635

A line of calligraphy:

wild geese above the foothills—

and a red moon for the seal.

—Taniguchi Buson (1716–1783)

3

Early September 1634

Like a dog waiting impatiently for scraps from the master’s table, Lord Matsudaira Tadateru’s ship, the

Sado Maru

, marked time in central California waters, waiting for the heavy fog that blanketed the coast to dissipate.

For the moment, Tadateru had company in his misery. The First Fleet, carrying the first wave of Japanese Christians to California, had passed between Point Reyes and the Farralones, and descended to a little below thirty-eight degrees north. It then headed east, hoping to at least catch a glimpse of the Golden Gate, the narrow opening to San Francisco Bay. Lord Matsudaira Tadateru expected to do more than that; he thought of it as his gateway to restored honor and fortune.

The weather, however, had been disappointing. For several days, the First Fleet had languished in the waters between the Farallones and the presumed location of the Golden Gate, without ever sighting the latter. The east was a featureless gray mass.

Tadateru reached up and, self-consciously, fingered his topknot, one of the marks of his samurai status. When he was disgraced and forced to become a Buddhist monk, his old one had been cut off and thrown onto a fire. When Tadateru accepted the shogun’s invitation to sail for the Golden Gate, and seek out the gold fields of California, he was given permission to grow it back. The shortness of his topknot was indicative of how recently he had been rehabilitated.

While Tadateru insisted on being addressed as “Lord Matsudaira,” he was unpleasantly aware of the emptiness of the title. He had been “provisionally” awarded a ten-thousand-

koku

fief, the minimum for daimyo status. However, the fief had been depopulated when its Christians came out of hiding and accepted exile to America. Hence, at least in the short term, it was virtually worthless.

It was quite a come down for a man who had once held a fief that annually produced over four hundred fifty thousand

koku

.

But it was better than being a monk. And at least his wife, Iroha-hime, was with him once more.

* * *

Belowdecks, in Iroha’s cabin, the floor was covered with clamshells. One hundred and eighty pairs take up a fair amount of room.

Iroha, sitting

seiza

style—buttocks on heels, knees together—had her eyes half-closed. She opened them, reached forward, and turned over two of the shells, a left and a right. Her action revealed that the insides of both were painted with the same image: Prince Genji visiting the holy man in his cave.

“Awase!”

she called out. Match!

Iroha and her maid Koya were playing

Kai-awase

, a game centuries old. The set had been part of her trousseau.

Iroha put the matched pair in her pile. It was much larger than Koya’s.

“I think you never forget a shell, Iroha-hime,” Koya said ruefully.

“Winning is all about remembering. And I don’t like to lose,” said Iroha. “Your turn.”

Koya gave her a sly look. “Do you think the real Prince Genji looked much like his picture, mistress?”

“Oh, yes. Almost as handsome as my husband.”

Iroha was just two years younger than Tadateru. Their marriage was, of course, political. Tadateru was the sixth son of Tokugawa Ieyasu, the then-ruler of Japan, and Iroha the eldest daughter of Date Masamune, one of the most powerful daimyo, who had sworn allegiance to Ieyasu after the Battle of Sekigahara in 1600.

Iroha smiled as she remembered how, shortly before their wedding, Tadateru had shyly handed her a letter, which she had tucked into a fold of her kimono, and opened as soon as she had a moment’s privacy.

It read: “My esteemed father has written, ‘patience is the source of eternal peace, treat anger as an enemy.’ Unfortunately, my temper is easily aroused, and this has gotten me into trouble on several occasions. I can assure you that my anger is usually a fleeting thing and I am almost always sorry afterward.

“I promise not to scold you without just cause. If I violate this promise, please show me this letter.”

Iroha still had the letter, despite all that had happened since. During the years of their marriage, he did get angry with her from time to time—once he had even thrown a sake cup at her—but he had always apologized. Sometimes just minutes later.

In 1612, she and her husband had met Luis Sotelo, the Franciscan, who was then living in Sendai under her father’s protection. Christianity had already been banned in the Tokugawa domains, but not in the rest of Japan. He had secretly converted them both to the Catholic faith. This forged another bond between them.

All was well until the spring of 1615, when Tadateru was summoned to lead his troops to war, the final struggle between the Tokugawa and the Toyotomi for control of Japan.

She shuddered involuntarily, as she remembered what followed.

“Iroha-hime, are you all right?” Koya said anxiously.

“So, sorry, Koya, I am tired all of a sudden. I think I will rest now. Please put the game away.”

* * *

At last, Date Masamune, the grand governor of “New Nippon,” decided that the First Fleet couldn’t linger any longer; it would have to leave Lord Matsudaira Tadateru, and the “Golden Gate,” behind. Iroha came to Masamune’s flagship to say goodbye.

As he watched her boat approach, Date Masamune brooded over her future. As a wedding gift, the shogun had given Tadateru the rich fief of Takada. But then he had squandered his good fortune by acting quite imprudently. In 1613, he was implicated in the Okubo conspiracy, to overthrow the shogun with Christian assistance. In 1615, during the summer campaign against the Toyotomi, he permitted Sanada Yokimura to retreat into Osaka Castle. The final straw was when he refused to join his older brother Hidetada on a visit to the imperial palace, pleading illness, and went hunting instead.

Tadateru had been forced to shave his head and become a Buddhist monk, exiled to the monastery at Kodasan. He had, under orders, divorced his wife Iroha. Rather than become a Buddhist nun, or commit

jigai

—cutting her own throat—she had endured the ultimate embarrassment for a woman of the samurai class: returning to her father’s home. And she had refused to even consider the possibility of remarriage.

Iroha had been overjoyed to hear of Tadateru’s “rehabilitation,” however provisional, and eagerly agreed to join him for the journey to the New World, even though they had not lived as husband and wife for nearly two decades. They had set sail for California less than a month after their reunion.

Date Masamune respected Iroha’s sense of duty. But he couldn’t help but think that her obligations to Tadateru were severed long ago, and were best left that way. Was he coming to the New World so that he and Iroha could enjoy life together? So that they could worship the Christian God?

No! Lord Matsudaira was here to restore his honor. That was fine . . . commendable . . . for him. But it was doubtful, very doubtful, that he saw Iroha’s presence as more than evidence that his shame was finally expiated.

Date Masamune resolved to make one more attempt to dissuade her from continuing on a course that he was sure would lead to more suffering.

Fathers have duties, too.

* * *

“Iroha-chan, life will be difficult enough for you in a colony of several thousand Nihonjin.” Date Masamune grimaced. “But assuming that Tadateru finds this Golden Gate, and enters San Francisco Bay, to remain in his company you will eventually have to trust yourself to a small boat making its way up the American River. You and your maid would be the only women on board, and you wouldn’t have private quarters. Even in the captain’s launch, his largest boat.”

“I am prepared for the . . . inconvenience.”

“It is not mere inconvenience that you face. Please, Daughter, look here.” He gestured at a map that was fastened to the wall of his cabin. “You will be traveling through San Francisco Bay, San Pablo Bay, the Carquinez Strait, and Suisun Bay, just to reach the Delta where the Sacramento and San Joaquin rivers meet. Then you must go about seventy miles upriver to the vicinity of the up-time town of Sacramento, and look for the mouth of the American River.

“And then Tadateru has no clear idea where to go! The river labeled as the American River is this one.” Her father pointed to the North Fork of the American. “But the encyclopedia said that Sutter’s mill, where the gold was found, was at Coloma.” His finger moved down two rivers, to the South Fork of the American. “Which is the unnamed river over here.

“And if that isn’t bad enough, the economic map in that same encyclopedia says that the nearest gold and silver is up here.” Masamune pointed to the California-Nevada border, near Reno. “In the high mountains.”

“Neither Tadateru nor any of his companions have any knowledge of the rivers, or of the savages that live on their banks. And none of you has experience in looking for gold, so it may be many months, or even years, before he finds what he is looking for.”

“My husband was given miners from Sado to help him.” Sado was the fabulous Japanese gold and silver mine that had been discovered in 1601.

“My advisers tell me that the gold of Sado is in hard rock, in quartz veins, while the Sutter’s Mill gold is probably

kawakin

.” Placer gold, the gold found in rivers and streams. “The encyclopedia says that it was found in a river, while building a sawmill. And those miners from Sado were extracting ore from a known vein, not looking for gold in the wilderness.”

“It doesn’t matter. I am his wife and it is my duty to follow him,” said Iroha.

“He did not take you with him to war, when he marched to Osaka, and neither should he take you with him on this chancy voyage of exploration.”

“If it is chancy,” Iroha said, “then that is all the more reason for me to come with him, as it may be my last chance on earth to see him.”

Masamune’s lips tightened. “If he truly cared for your well-being he would order you to remain with me.”

“It is because he cares for me so much that he permits me to come. And he knows that I do not care to live if he is dead.”

Masamune studied her expression. His own became stern. He was prepared to cause her a little pain now, if it would save her great hardship later. “You are not his wife. You were divorced by orders of the shogun.”

Iroha fought back tears, and Masamune in turn fought to remain impassive. She retorted, “The shogun had no power to divorce us. We were secretly baptized, and as secretly given the sacrament of matrimony according to the Holy Catholic Church.”

Masamune had long suspected this. Why else would she not have committed suicide? But in the Japan of Hidetada and Iemitsu, he had not dared to ask her, even in private.

Walls have ears, and stones tell tales

, his grandmother had told him.

“The shogun could break the bond formed by the public ceremony, the Buddhist one,” Iroha admitted. “But not the Christian one. We were not, we are not, divorced in the eyes of God, or in our hearts.

“Please, Father. When you gave him my hand in marriage, it became my duty under Japanese law to follow him, even if it meant disobeying you. But while I do not need your permission to go, I would like your blessing.”

“A blessing from a pagan?”

Iroha smiled faintly.

Masamune smiled briefly in turn. “I do not know whether you are in fact his wife, but you are most certainly my daughter. Stubbornness is what our family is known for. Yes, you have my blessing.”

“Thank you, Father. And I have a long day ahead of me, so please have me returned to my ship. And to my husband.”

* * *

Despite her brave words, Iroha was worried. She and Tadateru had lived apart for longer than they had lived together. At their reunion, Tadateru had been ebullient. But in the days that followed, as they made their preparations for departure, and then in the long sea voyage, she had caught unsettling glimpses of changes in him. The moments of happiness were fewer and shorter; those of anger or despair were more common and longer, than in the days before the siege of Osaka. Clearly, his long exile had darkened his soul. He seemed more, more—she searched for the word. Brittle.

Had it been up to her, they would just have declared themselves to be Christian, and accepted exile to New Nippon. Made a new life there, one free of the demands of rank.

But Tadateru had refused. For him, he said, it would just be another kind of exile. It would not erase the stain on his honor. Only his discovery of the gold fields, and his appointment as, oh, “Daimyo of Sacramento-han,” would do that.

Iroha had accepted his decision, of course. Her tutors had drummed into her, “be loyal to your husband, be brave in defense of his honor.”

But she worried that his decision might have repercussions, not just for her and Tadateru, but for her family. Her father had told her earlier in the voyage, “Iemitsu could have ordered

me

to go to San Francisco Bay. Or sent a faithful Tokugawa retainer. Why send Tadateru?” The likeliest explanation, in his opinion, was founded on Tadateru having one foot in the Tokugawa family, by blood, and the other amidst the Date, by marriage—the latter association being renewed now that Iroha had returned to him. Her father had concluded, “Clearly, if Tadateru succeeded, it would be proclaimed a Tokugawa success. And if he failed, it would be portrayed as a Date failure.”

Imachizuki, the Sleeping and Waiting Moon (Three Days After Full)

One day, at last, in the mid-afternoon, the fog began to lift, but there was no sign of any break in the coastline. The Japanese didn’t realize it, but the outline of the Berkeley Hills, on the opposite side of the Bay, and of Angel Island, merged into those of the northern and southern headlands framing the Golden Gate, thus concealing the presence of the Bay.

“May the makers of the American encyclopedia burn in Avichi, the lowest of the Hells, if they misdrew this San Francisco Bay,” Lord Matsudaira shouted, at no one in particular. The captain nodded in polite agreement.