1812: The Navy's War (14 page)

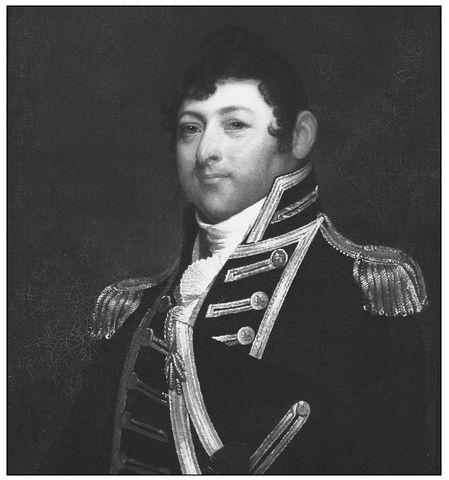

Figure 6.1: Samuel L. Waldo,

Commodore Isaac Hull, USN (1773-1843)

(courtesy of U.S. Naval Academy Museum).

Commodore Isaac Hull, USN (1773-1843)

(courtesy of U.S. Naval Academy Museum).

This was the

Constitution

’s first cruise since April 5, when Hull had put into the Washington Navy Yard for extensive repairs. Of the navy’s six major shipyards, where men-of-war were built, fitted out, and repaired, the Washington yard was generally considered the best and Portsmouth, New Hampshire, the worst. The others—New York, Boston, Philadelphia, and Norfolk—were rated in between. Hull considered New York better because it was supervised by Captain Isaac Chauncey. By putting into the Washington Navy Yard, however, he wasn’t sacrificing anything. The superintendent, Commodore Thomas Tingey, had been in charge since the yard’s inception in January 1800, and he had established a solid record.

Constitution

’s first cruise since April 5, when Hull had put into the Washington Navy Yard for extensive repairs. Of the navy’s six major shipyards, where men-of-war were built, fitted out, and repaired, the Washington yard was generally considered the best and Portsmouth, New Hampshire, the worst. The others—New York, Boston, Philadelphia, and Norfolk—were rated in between. Hull considered New York better because it was supervised by Captain Isaac Chauncey. By putting into the Washington Navy Yard, however, he wasn’t sacrificing anything. The superintendent, Commodore Thomas Tingey, had been in charge since the yard’s inception in January 1800, and he had established a solid record.

Hull had been skipper of the

Constitution

for two years, having taken command from John Rodgers on July 17, 1810. She was in poor condition then, not having had an extensive overhaul since 1803. Rodgers was leaving her because he wanted another ship, and, asserting his seniority, he had taken command of the

President

, which he considered the navy’s finest.

Constitution

for two years, having taken command from John Rodgers on July 17, 1810. She was in poor condition then, not having had an extensive overhaul since 1803. Rodgers was leaving her because he wanted another ship, and, asserting his seniority, he had taken command of the

President

, which he considered the navy’s finest.

Luckily, Nathaniel “Jumping Billy” Haraden, who had been the

Constitution

’s master during the war with Tripoli, was at the Washington yard in April, and he worked with Hull and his officers seven days a week to get the aged ship into fighting condition. Much work needed to be done; her copper was in bad shape, and so were her upper works. She needed a complete suit of sails and new running rigging. Her hull and decks needed caulking, the ballast washed, and the hold cleaned out. By the time war was declared, however, the big frigate was ready for action.

Constitution

’s master during the war with Tripoli, was at the Washington yard in April, and he worked with Hull and his officers seven days a week to get the aged ship into fighting condition. Much work needed to be done; her copper was in bad shape, and so were her upper works. She needed a complete suit of sails and new running rigging. Her hull and decks needed caulking, the ballast washed, and the hold cleaned out. By the time war was declared, however, the big frigate was ready for action.

The

Constitution

’s refurbishment exposed yet more ways in which the United States was unprepared for combat. Repairing and provisioning her had drawn down supplies and armament at the yard to a point where it could not serve the urgent needs of other warships and yards. Tingey was getting urgent requests from naval stations at Gosport, Wilmington, and Charleston for supplies, but he didn’t have them.

Constitution

’s refurbishment exposed yet more ways in which the United States was unprepared for combat. Repairing and provisioning her had drawn down supplies and armament at the yard to a point where it could not serve the urgent needs of other warships and yards. Tingey was getting urgent requests from naval stations at Gosport, Wilmington, and Charleston for supplies, but he didn’t have them.

Although the

Constitution

was now in excellent shape, Hull needed to add to the crew. Enlistments in the American navy were typically for two years, which meant that able seamen left the ship at regular intervals. In wartime this presented a big problem. A majority of Hull’s crew had signed on when he took command from Rodgers in 1810. Many of them had departed at the end of their tour and now had to be replaced.

Constitution

was now in excellent shape, Hull needed to add to the crew. Enlistments in the American navy were typically for two years, which meant that able seamen left the ship at regular intervals. In wartime this presented a big problem. A majority of Hull’s crew had signed on when he took command from Rodgers in 1810. Many of them had departed at the end of their tour and now had to be replaced.

Hull even had trouble holding on to his talented first lieutenant, Charles Morris. When the

Constitution

put into Washington in April, Morris tried to obtain a command of his own, since that was the surest path to rapid promotion. He had already had a distinguished career. During Decatur’s famous attack and burning of the captured

Philadelphia

during the war with Tripoli, Midshipman Morris was the first man to board the unlucky frigate. Secretary Hamilton recognized Morris’s ability and was sympathetic, but in the end he ordered him back to the

Constitution

. Needless to say, Hull was happy to see him return.

Constitution

put into Washington in April, Morris tried to obtain a command of his own, since that was the surest path to rapid promotion. He had already had a distinguished career. During Decatur’s famous attack and burning of the captured

Philadelphia

during the war with Tripoli, Midshipman Morris was the first man to board the unlucky frigate. Secretary Hamilton recognized Morris’s ability and was sympathetic, but in the end he ordered him back to the

Constitution

. Needless to say, Hull was happy to see him return.

On June 18 Hull sailed over to Annapolis to recruit crew members. Because of its proximity to Baltimore, where the war was popular, he thought recruitment would be easier than in thinly populated Washington. The

Constitution

departed Annapolis on July 5 with a full complement of four hundred forty men. Many of the newcomers had signed on in a fit of patriotic fervor. Not a few of them were green, however, and in need of training. Hull wrote to Hamilton, “The crew, you will readily conceive, must yet be unacquainted with a ship of war, as many of them have but lately joined us and never were in an armed ship before. We are doing all that we can to make them acquainted with [their] duty, and in a few days, we shall have nothing to fear from any single deck ship.”

Constitution

departed Annapolis on July 5 with a full complement of four hundred forty men. Many of the newcomers had signed on in a fit of patriotic fervor. Not a few of them were green, however, and in need of training. Hull wrote to Hamilton, “The crew, you will readily conceive, must yet be unacquainted with a ship of war, as many of them have but lately joined us and never were in an armed ship before. We are doing all that we can to make them acquainted with [their] duty, and in a few days, we shall have nothing to fear from any single deck ship.”

In spite of having thirty men sick from dysentery and the various maladies prevalent during the bay’s unhealthy summers, Hull worked the crew hard. As he made his way up Chesapeake Bay, practice at the guns and the sails went on every day. By the time he passed the Chesapeake Capes and pushed out to sea, Hull was conducting gunnery practice twice a day and felt the crew was rounding into shape.

Five days after Hull entered the Atlantic, on July 17, a lookout at the main masthead spied four strange sails to the northward and in shore of the

Constitution

. They were definitely men-of-war. The wind was light, and thinking they were part of Rodgers’s squadron, Hull threw on all sail and steered toward them.

Constitution

. They were definitely men-of-war. The wind was light, and thinking they were part of Rodgers’s squadron, Hull threw on all sail and steered toward them.

Around the same time, a lookout aboard H.M.S.

Shannon

saw a strange sail to the south and east standing to the northeast. He hollered down to the quarterdeck, where Broke soon had his telescope focused on the big ship in the distance. The

Shannon

was twelve miles east of Egg Harbor on the New Jersey coast. Broke had no doubt this was an American, and he gave the signal for a general chase. It was two o’clock in the afternoon. Broke’s squadron, in addition to the

Shannon

, included the 64-gun

Africa

and her tender, the 36-gun

Belvidera

, the 32-gun

Aeolus

, and the recently captured

Nautilus

with Lieutenant Crane still on board.

Shannon

saw a strange sail to the south and east standing to the northeast. He hollered down to the quarterdeck, where Broke soon had his telescope focused on the big ship in the distance. The

Shannon

was twelve miles east of Egg Harbor on the New Jersey coast. Broke had no doubt this was an American, and he gave the signal for a general chase. It was two o’clock in the afternoon. Broke’s squadron, in addition to the

Shannon

, included the 64-gun

Africa

and her tender, the 36-gun

Belvidera

, the 32-gun

Aeolus

, and the recently captured

Nautilus

with Lieutenant Crane still on board.

At four o’clock, one of Hull’s lookouts discovered another ship bearing northeast, standing for the

Constitution

with all her sail billowing. Hull thought she might be an American as well. For the next several hours the stranger sailed closer, but by sundown she was still too far away for her or the

Constitution

to distinguish recognition signals. The other four warships could only be seen from their tops.

Constitution

with all her sail billowing. Hull thought she might be an American as well. For the next several hours the stranger sailed closer, but by sundown she was still too far away for her or the

Constitution

to distinguish recognition signals. The other four warships could only be seen from their tops.

Hull decided to steer toward the single ship and approach near enough to make the night signal. At ten o’clock he hoisted signal lights and kept them aloft for almost an hour, but got no answer. He now felt certain this ship, as well as the four inshore, were British, and he “hauled off to the southward and eastward” to escape. The ship he had been chasing raced after him, making signals to the others as she went.

At daylight, two frigates from the inshore group had pulled closer to the

Constitution

—one of them to within five or six miles, while the other four ships were ten or twelve miles astern. All were in vigorous pursuit with a fine breeze filling their sails. In the area where the

Constitution

was, however, the wind had died. The ship “would not steer,” Hull recorded, “but fell round off with her head” toward her pursuers. In desperation, Hull ordered boats hoisted out and sent ahead to tow the ship’s head round and get on some speed. By now three enemy frigates were five miles away, but they, too, had lost their wind and had their boats out towing.

Constitution

—one of them to within five or six miles, while the other four ships were ten or twelve miles astern. All were in vigorous pursuit with a fine breeze filling their sails. In the area where the

Constitution

was, however, the wind had died. The ship “would not steer,” Hull recorded, “but fell round off with her head” toward her pursuers. In desperation, Hull ordered boats hoisted out and sent ahead to tow the ship’s head round and get on some speed. By now three enemy frigates were five miles away, but they, too, had lost their wind and had their boats out towing.

With the enemy ships continuing to close, Hull ordered the men to quarters. He then ran “two of the guns on the gun deck . . . out at the cabin window for stern guns, and hoisted one of the twenty-four pounders off the gun deck, and ran that, with a forecastle gun, an eighteen pounder, out” the taffrail, where carpenters had cut away spaces. At seven o’clock Hull fired one stern gun at the nearest ship, but the ball splashed harmlessly into the water.

By eight o’clock four enemy ships were nearly within gunshot range and coming up methodically. The breeze was insignificant. Hull’s situation looked desperate. “It . . . appeared we must be taken,” he wrote. But, no matter the odds, he would not surrender. He intended to fire as many broadsides as he could and go down fighting. Before resorting to this grim measure, however, he accepted Charles Morris’s suggestion that they try using kedge anchors. That required warping the ship ahead by carrying out kedge anchors in the ship’s boats, dropping them, and warping the ship up to them. The ship was in only twenty-four fathoms of water—shallow enough. He ordered his men to gather three hundred to four hundred feet of rope and sent two big anchors out.

The kedging allowed the

Constitution

to gradually pull ahead, but the British saw what Hull was doing, and they began using kedge anchors themselves. The ships farthest behind sent their boats to tow and warp those nearest the

Constitution

. Soon they were again getting closer to Hull. At nine o’clock the nearest ship, the

Belvidera

, began firing her bow guns. Hull replied with the stern chasers from his cabin and the quarterdeck. The

Belvidera

’s balls fell short, but Hull thought a couple of his hit home because he could not see them strike the water. Soon, H.M.S.

Guerriere

(the single ship Hull’s lookout had spotted before) pulled close enough to unload a broadside, but her balls all fell short. She quickly ceased firing and resumed the chase.

Constitution

to gradually pull ahead, but the British saw what Hull was doing, and they began using kedge anchors themselves. The ships farthest behind sent their boats to tow and warp those nearest the

Constitution

. Soon they were again getting closer to Hull. At nine o’clock the nearest ship, the

Belvidera

, began firing her bow guns. Hull replied with the stern chasers from his cabin and the quarterdeck. The

Belvidera

’s balls fell short, but Hull thought a couple of his hit home because he could not see them strike the water. Soon, H.M.S.

Guerriere

(the single ship Hull’s lookout had spotted before) pulled close enough to unload a broadside, but her balls all fell short. She quickly ceased firing and resumed the chase.

For the next three hours all hands on the

Constitution

were at the backbreaking task of warping the ship ahead with the heavy kedge anchors. To lighten and trim the ship, Hull pumped 2,300 gallons of drinking water—out of a total of almost 40,000—overboard, and with the help of a light air he gained a bit on his hounds.

Constitution

were at the backbreaking task of warping the ship ahead with the heavy kedge anchors. To lighten and trim the ship, Hull pumped 2,300 gallons of drinking water—out of a total of almost 40,000—overboard, and with the help of a light air he gained a bit on his hounds.

The British redoubled their efforts. At two o’clock in the afternoon all the boats from the battleship

Africa

and some from the frigates were sent to tow the

Shannon

. But as luck would have it, a providential breeze sprang up that enabled Hull to maintain his lead. The light wind stayed with the

Constitution

until eleven o’clock that night, and with her boats towing, she was able to keep ahead of the

Shannon

. Shortly after eleven, the

Constitution

caught a strengthening southerly wind that brought her abreast of her boats, which she hoisted up without losing any speed. Her pursuers were still near, but she was holding her own. To keep up, the

Shannon

abandoned her boats as the wind took her.

Africa

and some from the frigates were sent to tow the

Shannon

. But as luck would have it, a providential breeze sprang up that enabled Hull to maintain his lead. The light wind stayed with the

Constitution

until eleven o’clock that night, and with her boats towing, she was able to keep ahead of the

Shannon

. Shortly after eleven, the

Constitution

caught a strengthening southerly wind that brought her abreast of her boats, which she hoisted up without losing any speed. Her pursuers were still near, but she was holding her own. To keep up, the

Shannon

abandoned her boats as the wind took her.

The ships sailed through the second night of their engagement with Hull maintaining his lead by employing every device he could think of. A portion of the log read: “At midnight moderate breeze and pleasant, took in the royal studding sails.... At 1 A.M. set the sky sails [they had just been installed at the Washington Navy Yard]. At [1:30] got a pull of the weather brace and set the lower [studding] sail. At 3 A.M. set the main topmast studding sail. At [4:15] hauled up to SE by S.” And so it went, as Hull, the great maestro, employed every instrument at his command.

At daylight on the nineteenth, six enemy ships were still visible. Hull now had to tack to the east, and in doing so, he passed close to the 32-gun

Aeolus

. The

Constitution

braced for a broadside, but the British frigate held her fire. Perhaps she feared becalming, “as the wind was light,” Hull speculated. In any event, after the

Constitution

passed, the

Aeolus

tacked and commenced her pursuit again.

Aeolus

. The

Constitution

braced for a broadside, but the British frigate held her fire. Perhaps she feared becalming, “as the wind was light,” Hull speculated. In any event, after the

Constitution

passed, the

Aeolus

tacked and commenced her pursuit again.

At 9 A.M. an innocent American merchantman happened on the scene. The British ships instantly hoisted American colors to decoy her toward them. Hull responded by hoisting British colors. The merchantman’s skipper correctly assessed the situation, hauled his wind, and raced away.

As the day progressed, the wind increased, and the

Constitution

gained on her pursuers, lengthening her lead to as much as eight miles, but Broke kept after her—all through the day and night.

Constitution

gained on her pursuers, lengthening her lead to as much as eight miles, but Broke kept after her—all through the day and night.

At daylight on the twentieth, only three pursuers were visible from the

Constitution

’s main masthead, the nearest being twelve miles astern. Hull set all hands to work wetting the sails, from the royals down, “with the engine and fire buckets, and we soon found that we left the enemy very fast,” Hull reported.

Constitution

’s main masthead, the nearest being twelve miles astern. Hull set all hands to work wetting the sails, from the royals down, “with the engine and fire buckets, and we soon found that we left the enemy very fast,” Hull reported.

Commodore Broke recognized that even his lead ships were falling behind at an increasing rate, and at 8:15 he conceded the superior seamanship of the American and gave up the chase.

When Hull saw Broke hauling his wind and heading off to the north, he was enormously proud of his crew. They might have been green, but in a grueling, fifty-seven-hour chase, they had outsailed every one of Broke’s ships. It was an amazing display of seamanship, stamina, collaborative effort, and, indeed, patriotism. And especially so when one considers that Commodore Broke was among the best in the business. The

Constitution

’s crew had beaten Britain’s finest.

Constitution

’s crew had beaten Britain’s finest.

Having won this singular race in spectacular fashion, Hull now decided to make for Boston instead of New York, where his orders had directed him to go. He assumed Broke would be steering toward Sandy Hook to begin a blockade of New York, and he certainly did not want to run into him again.

Other books

Order of The Rose: Forsaken Petal by Hoyt, Joshua

Right from the Gecko by Cynthia Baxter

The Everything Theodore Roosevelt Book by Arthur G. Sharp

Somewhere I Belong by Glenna Jenkins

Once A Hero by Michael A. Stackpole

The Amber Room by T. Davis Bunn

Sleeping Freshmen Never Lie by David Lubar

Rena's Promise by Rena Kornreich Gelissen, Heather Dune Macadam

The Good Lie by Robin Brande

Forever And A Day (Montana Brides, Book #7) by Leeanna Morgan