2008 - A Case of Exploding Mangoes (3 page)

Read 2008 - A Case of Exploding Mangoes Online

Authors: Mohammed Hanif

I wonder for a moment what Obaid would do in this cell. The first thing that would have bothered him is the smell 2

nd

OIC has left behind. This burnt onions, home-made yogurt gone bad smell. The smell of suspicion, the smell of things not quite having gone according to plan. Because our Obaid, our Baby O, believes that there is nothing in the world that a splash of Poison on your wrist and an old melody can’t take care of.

He is innocent in a way that lonesome canaries are innocent, flitting from one branch to another, the tender flutter of their wings and a few millilitres of blood keeping them airborne against the gravity of this world that wants to pull everyone down to its rotting surface.

What chance would Obaid have with this 2

nd

OIC? Baby O, the whisperer of ancient couplets, the singer of golden oldies. How did he make it through the selection process? How did he manage to pass the Officer-Like Qualities Test? How did he lead his fellow candidates through the mock jungle survival scenarios? How did he bluff his way through the psychological profiles?

All they needed to do was pull down his pants and see his silk briefs with the little embroidered hearts on the waistband.

Where are you, Baby O?

Lieutenant Bannon saw us for the first time at the annual variety show doing our Dove and Hawk dance. This was before the Commandant replaced these variety shows with Quran Study Circles and After Dinner Literary Activities. As third-termers we had to do all the shitty fancy-dress numbers and seniors got to lip-sync to George Michael songs. We were miming to a very macho, revolutionary poem. I, the imperialist Eagle, swooped down on Obaid’s Third World Dove; he fought back, and for the finale sat on my chest drawing blood from my neck with his cardboard beak.

Bannon came to meet us backstage as we were shedding our ridiculous feathers. “Hooah, you zoomies should be in Hollywood!” His handshake was exaggerated and firm. “Good show. Good show.” He turned towards Obaid, who was cleaning the brown boot polish from his cheeks with a hankie. “You’re just a kid without that warpaint,” Bannon said. “What’s your name?”

In the background, Sir Tony’s ‘Careless Whisper’ was so out of tune that the speakers screeched in protest.

Under his crimson beret, Bannon’s face was beaten leather, his eyes shallow green pools that had not seen a drop of rain in years.

“Obaid. Obaid-ul-llah.”

“What does it mean?”

“Allah’s servant,” said Obaid, sounding unsure, as if he should explain that he didn’t choose this name for himself.

“What does your name mean, Lieutenant Bannon?” I came to Obaid’s rescue.

“It’s just a name,” he said. “Nobody calls me Lieutenant. It’s Loot Bannon for you stage mamas.” He clicked his heels together and turned back to Obaid. We both came to attention. He directed his over-the-top, two-fingered salute at Obaid and said the words which in that moment seemed like just another case of weird US military-speak but would later become the stuff of dining-hall gossip.

“See you at the square, Baby O.”

I felt jealous, not because of the intimacy it implied, but because I wished I had come up with this nickname for Obaid.

I make a mental note of the things they could find in the dorm to throw at me:

- One-quarter of a quarter-bottle of Murree rum

- A group photo of first-termers in their underwear (white and December-wet underwear actually).

- A video of

Love on a Horse

. - Bannon’s dog-tags, still listed as missing on the guardroom’s Lost and Found noticeboard.

If my Shigri blood wasn’t so completely void of any literary malaise, I would have listed poetry as Exhibit 5, but who the fuck really thinks about poetry when locked up in a cell unless you are a communist or a poet?

There is a letter-box slit in the door of the cell, as if people are going to send me letters.

Dear All Shigri, I hope you are in the best of health and enjoying your time in…

I am on my knees, my eyes level with the letter-box slit. I know Obaid would have lifted the flap on the slit and would have sat here looking at the parade of khaki-clad butts, and amused himself by guessing which one belonged to whom. Our Baby O could do a detailed personality analysis just by looking at where and how tightly people wore their belts.

I don’t want to lift the flap and find someone looking at me looking at them. The word is probably already out. That butcher Shigri is where he deserves to be, throw away the key.

The flap lifts itself, and the first-termer shitface announces my dinner. “Buzz off,” I say, regretting it immediately. Empty stomach means bad dreams.

In my dream, there is a Hercules C13O, covered with bright flowers like you see on those hippie cars. The plane’s propellers are pure white and move in slow motion, spouting jets of jasmine flowers. Baby O stands on the tip of the right wing just behind the propeller, wearing a black silk robe and his ceremonial peaked cap. I stand on the tip of the left wing in full uniform. Baby O is shouting something above the din of the aircraft. I can’t really make out any words but his gestures tell me that he is asking me to come to him. As I take the first step towards Baby O, the C13O tilts and goes into a thirty-degree left turn, and suddenly we are sliding along the wings, heading for oblivion. I wake up with one of those screams that echoes through your body but gets stuck in your throat.

In the morning they throw poetry at me. Rilke, for those interested in poetry.

The Officer in Command of our Academy, or the Commandant as he likes to call himself, is a man of sophisticated tastes. Well-groomed hair, uniform privately tailored, Staff and Command College medals polished to perfection. Shoulder flaps full. OK, the crescent and crossed swords of a two-star general haven’t arrived, but this guy is having a good time waiting for all of that.

Some crumpled sheets of paper stuffed in the obligatory gash in my mattress are what they find.

Clues

, they think.

I don’t read poetry and used to refuse to even pretend to read the strange poetry books that Obaid kept giving me. I always made the excuse that I can only appreciate poetry in Urdu, so he went ahead and translated this German guy’s poems into Urdu for my birthday, wrote them in rhyming Urdu since I had also taken a stand against poetry that didn’t rhyme. He translated five poems in his beautiful calligrapher’s handwriting, all little curves and elegant dashes, and pasted them on the inside of my cupboard.

In the clean-up operation that I carried out the morning of his disappearance, I stuffed them into the mattress, hoping that 2 OIC would not go that far in his search for the truth.

I have thought of most things and have ready answers, but this one genuinely baffles me. What are they going to charge me with? Rendering foreign poetry into the national language? Abuse of official stationery?

I decide to be straight about it.

The Commandant finds it funny.

“Nice poem,” he says straightening the crumpled paper. “Instead of the morning drill, we should start daily poetry recitals.”

He turns to 2

nd

OIC. “Where did you find it?”

“In his mattress, sir,” 2

nd

OIC says, feeling pleased with himself, having gone way beyond the call of his bloody duty.

Rilke is crumpled again and the Commandant fixes 2

nd

OIC with a look that only officers with inherited general-genes are capable of.

“I thought we took care of that problem?”

Serves you right, asshole, my inner cadence booms.

The Commandant has his finger on the pulse of the nation, always adjusting his sails to the winds blowing from the Army House. Expressions like

Almighty Allah

and

Always keep your horses ready because the Russian infidels are coming

have been cropping up in his Orders of the Day lately, but he has not given up on his very secular mission of getting rid of foam mattresses with holes.

“You know why we were a better breed of officers? Not because of Sandhurst-trained instructors. No. Because we slept on thin cotton mattresses, under coarse woollen blankets that felt like a donkey’s ass.”

I look beyond his head and survey the presidential inspection photos on the wall, the big shiny trophies caged in a glass cupboard, and try to find Daddy.

Yes, that nine-inch bronze man with pistol is mine. Best Short Range Shooting Shigri Memorial Trophy, named after Colonel Quli Shigri, won by Under Officer Ali Shigri.

I don’t want to think right now about Colonel Shigri or the ceiling fan or the bed sheet that connected them. Thinking about Dad and the ceiling fan and the bed sheet always makes me either very angry or very sad. Not the right place for either of these emotions.

“And now look at them,” the Commandant turns towards me. My arms lock themselves to my sides, my neck subtly shifts itself into a position so that I can keep staring at the bronze man.

“Spare me,” I think, “I didn’t invent the bloody technology that makes foam mattresses.”

“And these pansies…” Nice new word, I tell myself. This is how he maintains his authority. By coming up with new expressions that you don’t really understand but know what they mean for you.

“These pansies sleep on nine-inch thick mattresses under silky bloody duvets and every one of them thinks that he is a Mughal bloody princess on her honeymoon.” He hands over the crumpled Rilke to 2

nd

OIC, a sign that the interrogation can proceed.

“Is this yours?” 2

nd

OIC asks, waving the poems in my face. I try to remember something from the poems but get stuck on a half-remembered line about a tree growing out of an ear, which is weird enough in English but sounds completely crazy in rhyming Urdu. I wonder what the bugger was writing in German.

“No, but I know the handwriting,” I say.

“We know the handwriting too,” he says triumphantly. “What is it doing in your mattress?”

I wish they had found the bottle of rum or the video. Some things are self-explanatory.

I stick with the truth.

“It was a birthday present from Cadet Obaid,” I say. 2

nd

OIC hands the poems back to the Commandant, as if he has just rested his case whatever the case is.

“I have seen all kinds of buggers in this business,” the Commandant starts slowly. “But one pansy giving poetry to another pansy, then the other pansy stuffing it in the hole in his mattress is a perversion beyond me.”

I wanr to tell him how quickly a new word can lose its charm with overuse, but he is not finished yet.

“He thinks he is too smart an ass for us.” He addresses 2

nd

OIC who is clearly enjoying himself. “Get ISI to have a word with him.”

I know he is still not finished.

“And listen, boy, you might be a clever dick and you might read all the pansy poetry in the whole world but there is one thing you can’t beat. Experience. How is this for poetry? When I started wearing this uniform…”

I have a last look at the bronze man with the pistol. Colonel Shigri’s bulging eyes stare at me. Not the right place, I tell myself.

The Commandant senses my momentary absent-mindedness and repeats himself. “When I started wearing this uniform, you were still in liquid form.”

2

nd

OIC marches me out of the Commandant’s office. On my way back I try to avoid the salutes offered by cadets marching past me. I try to pretend I am having a leisurely stroll with 2

nd

OIC, which will end in my dorm rather than the cell.

All I can think about is the ISI.

It has to be an empty threat. They cannot call in the Inter bloody Services bloody Intelligence just because a cadet has gone AWOL. ISI deals with national security and spies. And who the fuck needs spies these days anyway? The US of A has got satellites with cameras so powerful they can count the exact number of hairs on your bum. Bannon showed us a picture of this satellite and claimed that he had seen bum pictures taken from space but couldn’t show them to us because they were classified.

ISI also does drugs but we have never done drugs. OK, we smoked hash once, but in the mountains I come from, hashish is like a spice in the kitchen, for headaches and stuff. Obaid got some from our washerman Uncle Starchy and we smoked one moonlit night in the middle of the parade square. Obaid had a singing fit and I practically had to gag him before bringing him back to our dorm.

I need to get an SOS to Bannon.

Shit on a shingle. Shit on a shingle.

B

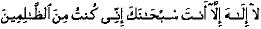

efore morning prayers on 15 June 1988, General Mohammed Zia ul-Haq’s index finger hesitated on verse 21:87 while reading the Quran, and he spent the rest of his short life dreaming about the innards of a whale. The verse also triggered a security alert that confined General Zia to his official residence, the Army House. Two months and two days later, he left the Army House for the first time and was killed in an aeroplane crash. The nation rejoiced and never found out that General Zia’s journey towards death had started with the slight confusion he experienced over the translation of a verse on that fateful day.

In Marmaduke Pickthall’s English translation of the Quran, verse 21:87 reads like this:

And remember Zunnus, when he departed in wrath: he imagined that We had no power over him! But he cried through the depths of darkness, “There is no god but thou: glory to thee: I was indeed wrong!

”

When General Zia’s finger reached the words

I was indeed wrong

, it stopped. He retraced the line with his finger, going over the same words again and again with the hope of teasing out its true implication. This was not what he remembered from his earlier readings of the verse.

In Arabic it says: