(2/20) Village Diary (21 page)

Read (2/20) Village Diary Online

Authors: Miss Read

Tags: #Fiction, #England, #Country life, #Country Life - England, #Fairacre (England : Imaginary Place)

SEPTEMBER

E

RLE

arrived on the doorstep at nine-thirty this morning, armed with a box of chocolates, a bouquet of pink carnations and a note of thanks and farewell from his parents. It was a typically American gesture of generosity and courtesy, and I was much touched.

'We're off to Southampton right now,' said Erie, when I asked him in, 'so I mustn't.' He offered me his hand solemnly.

'Well, I guess it's good-bye,' he said, pumping mine energetically up and down. He nodded his crew-cut across at the little school.

'That's the best school I've ever been teached at!' he said warmly.

I watched him run up the lane, somewhat comforted by this compliment. I shad not forget Erie. He and his classmates at Fairacre School have been living proof of Anglo-American friendship.

Mr Roberts brought me over a basket of plums this evening—the first, I suspect, of many which will find their way from generous neighbours to the school-house.

He told me that Abbot, his cowman, is leaving him at Michaelmas.

'He's got a job at the research station evidently,' said Mr Roberts. 'His brother's there already, and he's found them a house nearby. Another good man leaving the village—I don't like to see it.'

I asked him why he was going.

'Well, the hours are shorter, for one thing. Cows have to be milked, Sundays and ad, and there's no knowing when a cowman may not have to spend a night up with a sick cow. It's heavy work too. I think the women have a lot to do with their menfolk leaving the land. They look upon farmwork as something inferior. If they can say: "My husband works at Garfield" instead of "at Roberts' old farm." they feel it's a step up the social ladder.'

'Will he get more money?' I asked.

'Yes, he will. But his rent will be three times what it is now—and though I says it as shouldn't—he will be lucky to find as easy a landlord.' I knew this to be true, for Mr Roberts's farm cottages are kept in good repair.

'Oh yes, his pay will go up,' said Mr Roberts somewhat bitterly, 'but what a waste of knowledge! It's taken forty years to make that good cowman; I'd trust him with a champion, that chap—and all that's to be wasted on some soulless routine job that any ass could do. And where am I to get another? The days have gone when I could go to Caxley Michaelmas Fair and give my shilling to one of a row of good cowmen waiting to be hired—as my father did!'

I felt very sorry for Mr Roberts, as he stood, kicking morosely with his enormous boots at my doorstep, pondering this sad problem. This is only one case, among many, of old village families leaving their ancient home and going to bigger centres to find new jobs. There must be some positive answer to this drift from the country to the town. It cannot be only the promise of high wages that draws the countryman, though naturally that is the major attraction, offering as it does an easier mode of living for his wife and family.

'I picks up five pound a week for doing nothing,' boasted one elderly villager recently. Sad comment indeed, if this is true, on the outlay of public money and of his own starved mental outlook.

Perhaps, for a family man, the advantages of bigger and more modern schools for his children are an added incentive; and I thought again of Mr Annett's outburst about his own all-standard country school, which, he is clear-sighted enough to see, runs a poor second to the new secondary modern school which can offer so much more to his older children.

The new school year started today, and we have forty-three children in Fairacre School.

Miss Jackson is esconced in the infants' room with twenty children, aged from five to seven; and I have the rest, up to eleven years of age, in my class.

Among the new entrants is Robin Pratt, who created such a dramatic stir one year, when we went on our outing to Barrisford, by suffering an accident to his eye. His sister Peggy has been promoted to my class this term, and as Robin was rather tearful on his first morning, he was allowed to sit with her until he felt capable of facing life in the infants' room, without any family support. His eye has suffered no permanent damage, and he is going to be a most attractive addition to the infants' class.

Miss Jackson has been unable to get lodgings in the village, and is with me at the moment. She is rather heavy going, and inclined to 'tell me what' in a way which I find mildly offensive. However, I put it down to youth and, perhaps, a little shyness, though the latter is not apparent in any other form. Getting her up in the morning is going to be a formidable task, I foresee, if she sleeps as heavily as she did last night. It was eight o'clock before I finally roused her, and my fifth assault upon the spare-room door.

The wet weather, which persisted through the major part of the holidays, has now—naturally enough—taken a turn for the better. The farmers look much more hopeful as they set about getting in a very damp harvest, and Mr Roberts' corn-drier hums a cheerful background drone to our schoolday.

To my middle-aged eye, the new entrants appear more babylike than ever, and my top group more juveiule than ever before; but this I find is a perennial phenomenon, and I can only put it down to advancing age on my part. For I notice too, these days, how irresponsibly young ad the policemen look, and on my rare visits to Oxford or Cambridge I find myself looking anxiously about to see who is in charge of the undergraduate innocents, dodging at large among the traffic.

Yesterday evening Mr Mawne called at the school-house, bearing yet another basket of plums. This makes the seventh plum-offering to date, and really they are becoming an embarrassment.

Miss Jackson and I were about to start our supper of ham and salad, and we invited him to join us. This he seemed delighted to do, making a substantial meal and finishing up all the cheese and bread in the house, so that we were obliged to have our breakfast eggs this morning without toast, but with Ryvita.

He told us, in some detail, about his correspondence with his friend Huggett on the subject of the purple sandpiper, and it was eleven o'clock before he made a move to return to his own home. Miss Jackson bore up very well, taking a markedly intelligent interest in all Mr Mawne's exhaustive (and to my mind, exhausting) data on birds; but I was in pretty poor shape by ten o'clock, answering mechanically 'Oh!' and 'Really?' between badly-stifled yawns. Although I am not averse to Mr Mawne, and realize that his life is—as he himself has frequently told me—a trifle lonely, yet I must confess that, to put it plainly, I find him a bore.

'What an interesting man!' enthused Miss Jackson, as I closed the front door thankfully upon him. 'He's just what you need—a really stimulating companion!'

More dead than alive, I crawled to bed.

This morning Mrs Pringle said that she hoped I'd enjoyed my evening with Mr Mawne, and it was shameful the way his underclothes wanted mending.

'I'm doing for him while his housekeeper's having her fortnight's break,' she told me. 'If ever a man needed a woman to look after him, that poor Mr Mawne does. He sits about, moping in an armchair, with me dusting round him, as you might say. And not a rag has he got to his back that doesn't need a stitch somewhere!'

I said, with some asperity, that that was no concern of mine, and had she removed my red marking pen from the ink stand.

Ignoring this retreat to safer ground, Mrs Pringle sidled nearer, dropping her usual bellow to an even more offensive lugubrious whine.

'Ah! But there's plenty thinks as you should make it your concern. He's fair eating his heart out—and the whole village knows it, but you!'

This was the last straw. I had suffered enough, heavens knows, from hints and knowing glances lately, but now that Mrs Pringle had the temerity and impertinence to bring this into the open, I had the chance to put my side plainly.

I pointed out, with considerable hauteur, that she was doing a grave injustice to Mr Mawne and to me, that to repeat idle gossip was not only foolish, but could be scandalous, in which case I should have no hesitation in asking for my solicitor's advice and recommending Mr Mawne to do the same.

At the dread name of 'solicitor' even Mrs Pringle's complacency buckled, and seeing her unwonted abjection, I hastened to press home my attack.

'Understand this,' I said in the voice I keep for those about to be caned, 'I will have no more behind-hand tittle-tattle about this poor man and me. I count upon you to give the lie to such utter rubbish that is flying about Fairacre. Meanwhile I shall write for legal advice this evening.'

Purple-faced, but silent, Mrs Pringle positively slunk back to her copper in the lobby; whilst I, full of righteous wrath, looked out our morning hymn.

Fight the good fight

seemed as proper a choice as any, and my militant rendering so shook the ancient piano that quite a large shred of red silk fell from behind its fretwork front and landed among the viciously-pounded keys.

***

Throughout the day Mrs Pringle maintained a sullen silence and, as I expected, arrived at the school-house after tea to give in her notice. This is the eighth or ninth time she has done this and, as usual, I accepted it with the greatest enthusiasm.

'I am delighted to hear that you are giving up,' I told her truthfully. 'After this morning's disclosures, it's the best possible thing for you to do!'

Mrs Pringle bridled.

'Never been spoke to so in my life,' she boomed. 'Threatened me—that's what you done. I said to Pringle: "I've had plenty thrown in my face-but when it comes to solicitors—Well!" So you must make do without me in the future.'

I said that we should doubtless manage very well, wished her good night and returned to the sitting-room. Miss Jackson looked up with a scared expression.

'I say! What an awful row! What will you do without her?'

'Enjoy myself,' I said stoutly. 'Not that I shall get the chance. She'll turn up again in a day or two, and as there's really no one else to take the job on, we'll shake down together again I expect. It'll do her good to lose a few days' pay and to turn things over in her mind for a bit. Offensive old woman!'

Much exhilarated by this encounter I propped up on the mantelpiece the grubby scrap of paper—torn from the rent book I suspected—on which Mrs Pringle had announced her retirement, and suggested that we celebrated in a bottle of cider.

'Lovely!' said Miss Jackson, catching my high spirits and beaming through her unlovely spectacles, 'and if you like I'd make tomato omelettes for supper!'

And very good they were.

I have paid my promised visit to the Annetts to see Malcolm (not Oswald, I am relieved to know). He is a neat, compact, little baby, who eats and sleeps well, and is giving his mother as little trouble as can be expected from someone who needs attention for twenty-two hours out of the twenty-four.

I felt greatly honoured when I was asked to be godmother and accepted this high office with much pleasure, for although I have two delightful goddaughters, this will be my only godson. The christening is fixed for the first Sunday in October and I am looking forward to a trip into Caxley to find a really attractive silver rattle and coral, worthy of such a fine boy.

'My brother Ted is to be one of the godfathers,' said Mr Annett, 'and Isobel's cousin, who is in the Merchant Navy, is the other. With any luck he may have shore leave just then. If not, I'll stand proxy.'

He rubbed his hands gleefuly.

`I must say I enjoy a party,' he went on. 'We'll have a real good one for every baby we have. Will you take it as a standing invitation?'

I said indeed I would, and that I looked forward to many happy occasions. But Mrs Annett, I noticed, was not so enthusiastic.

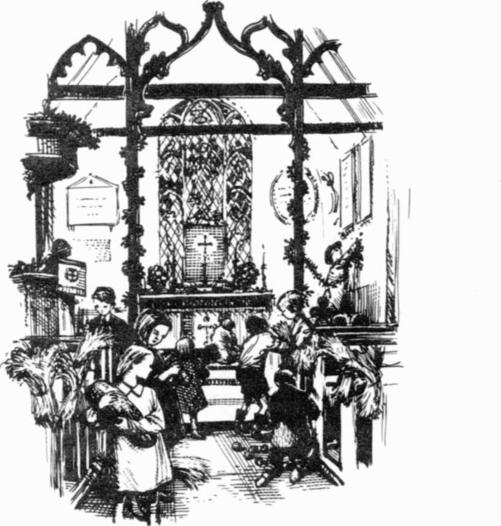

As is customary in Fairacre at harvest time, the children at the school helped to decorate the church for Harvest Festival.

Mr Roberts sent over a generous sheaf of corn and the children had a blissful morning tying it into small bundles to decorate the ends of the pews. The floor was littered with straw and grain, and I was glad that Mrs Pringle had given in her notice and that we could make as much mess as we liked without hearing many sour comments when that lady passed through the classroom.

Miss Jackson was inclined to be scathing about our efforts and also about the use to which we should apply the fruits of our labours.

'Straw,' she announced, 'is a most difficult medium for children to work in. Why, even the Ukrainians, who are acknowledged to be the most inspired straw-workers, reckon to serve an apprenticeship—or so our psychology teacher told us.'

One of the Coggs twins held up a fistful of ragged ears for my inspection at this point.

'Lovely!' I said, tying it securely with a piece of raffia, 'that will look very nice at the end of a pew.'

Flattered, she swaggered back to her place on the floor, collecting her second bunch with renewed zest. Miss Jackson looked scornful.

'And I don't know that it's not absolutely primitive—all this corn and fruit and stuff! Makes one think of fertility rites. I did a thesis on them for Miss Crabbe at college.'

'Harvest Festival,' I said firmly, 'is a good old Christian custom, and we here in Fairacre put our hearts into it. If you object to such practices, I don't quite know why you have accepted an appointment in a church school.' She had the grace to look abashed, and the preparations went forward without further comment, except for one dark mutter about it being a good thing that Miss Crabbe—the psychology lecturer, who seems to have exerted a disproportionate influence on my assistant—doesn't live in Fairacre; with which statement I silently concurred.