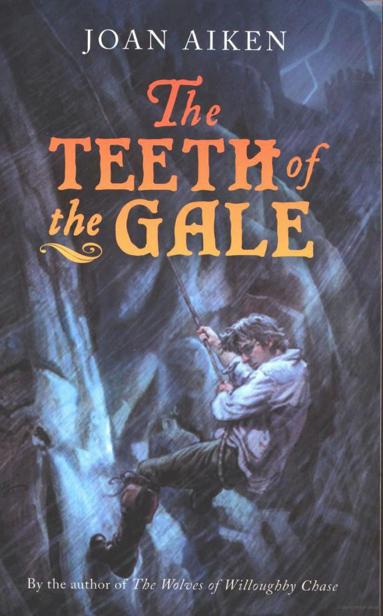

(2/3) The Teeth of the Gale

Read (2/3) The Teeth of the Gale Online

Authors: Joan Aiken

Joan Aiken

H

ARCOURT

, I

NC

.

Orlando Austin New York San Diego Toronto London

Copyrignt © 1988 by John Sebastian Brown and

Elizabeth Delano Charlaff

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or

transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical,

including photocopy, recording, or any information storage and retrieval

system, without permission in writing from the publisher.

Requests for permission to make copies of any part of the work

should be submitted online at

www.harcourt.com

/contact or mailed

to the following address: Permissions Department, Harcourt, Inc.,

6277 Sea Harbor Drive, Orlando, Florida 32887-6777.

First published in Great Britain by Jonathan Cape, 1988

First U.S. edition published by HarperCollins, 1988

First Harcourt paperback edition 2007

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Aiken, Joan, 1924–2004.

The teeth of the gale/Joan Aiken,

p. cm.

Sequel to: Bridle the wind.

Summary: At the request of the nun with whom he is in love,

eighteen-year-old Felix embarks on a perilous rescue mission

across the strife-torn countryside of Spain in the late 1820s.

1. Spain—History—Ferdinand VII, 1813–1833—Juvenile fiction.

[1. Spain—History—Ferdinand VII, 1813–1833—Fiction.

2. Adventure and adventurers—Fiction.] I. Title.

PZ7.A2695Te 2007

[Fic]—dc22 2006022955

ISBN

978-0-15-206070-1

Text set in Adobe Garamond

Designed by Cathy Riggs

A C E G H F D B

Printed in the United States of America

CHAPTERSTo Else-Marie Bonnet

1

In which I receive a message from home; travel with Pedro; am followed by Sancho the Spy; see a spoiled child and her fat father; give our pursuers the slip; and witness a fearsome landslide

[>]

2

I return home and hear heartwarming news from a convent in Bilbao; Pedro and I prepare for another journey; strange tidings of Sancho the Spy

[>]

3

Arrival at the Convent—was it Juana? I take a dislike to the Reverend Mother; am received by Doña Conchita's parents; we receive permission to set out—and do so with too much luggage

[>]

4

Conversations with Doña Conchita; Juana and Sister Belen speak in Latin; a night at Irurzun

[>]

5

We pass through Pamplona; the fat man again; I ask God for a sign; arrival at Berdun; the unaccountable scream; the mysterious creature in Don Ignacio's chimney; I receive my sign from God; and hold a moonlit conversation with Juana

[>]

6

Trouble with the Escaroz horses; Pedro and I go to the monastery of San Juan; there we meet "Figaro"; I return to Berdun; am surprised at the municipal arrangements for refuse; Doña Conchita objects to being carried in a lobster pot; more news of the fat man

[>]

7

Arrival at the rope bridge; the bear; Pedro stunned; I encounter little Pilar on a cliff; Don Manuel and his children; the book; I carry a letter to Juana

[>]

8

We meet Don Amador; a night in the cave; reappearance of Figaro

[>]

9

Juana's decision; return to the castillo; terrible news; Don Manuel and his wife; Conchita's downfall; departure of Manuel and Figaro

[>]

10

We leave the castillo; crossing the rope bridge; Pedro is shot; I become unconscious

[>]

11

In the tartana; little Pilar makes herself useful; arrival at Berdun; a use for the rubbish chute; we find a doctor; we return to Bilbao, where I receive bad news from home

[>]

12

At Villaverde; the old ladies and their bird; good-bye to Grandfather

[>]

13

Sister Milagros gives me her message at last; a surprise in the infirmary; a surprise from the Reverend Mother; our affairs are brought to a conclusion

[>]

Afterword

[>]

Reading List

[>]

It was on some saint's day—whose, I don't remember—that Pedro came knocking at the door of my lodging in Salamanca. The townspeople had been celebrating since dawn, with processions, fireworks, bullfights, and dancing in the streets; the students at the University had a holiday, and most of them had been out, waving banners and demanding more liberal laws. Many of them had by this time been arrested and were probably in bad trouble. By nightfall, most of the town's activities were concentrated in the Plaza Mayor, the main square, onto which my window faced. People who still had the energy—and there were plenty of them—were dancing; the older citizens sat at tables under trees in the middle of the plaza and drank wine and coffee and talked.

People talk more, in Salamanca, I have heard it said, than in any other town in the world. The sound of their conversation came up through my window—open, for it was a mild spring evening—in a solid clatter, like the tide breaking on a pebbled shore, just sometimes overborne by bursts of music on pipe, drum, and guitar.

For this reason it was some time before I noticed the tapping and scratching at my door, and heard Pedro's voice.

"Felix, Felix! Are you in there?

Ay, Dios,

what a struggle I've had, shoving my way here through the crowd—" as I opened the door and let him in. "I reckon the whole town is packed into the square down below. Why aren't

you

out there, drinking and dancing with the girls? Or carrying placards with the students? Mind, I'm just as glad you are not; it would be like trying to find one leaf in a forest."

"Pedro! What in the wide world are

you

doing here, in Salamanca?"

It was at least eighty leagues from home, two and a half days' riding at a horse's best pace. And Pedro, I knew, could not easily be spared these days; he had risen from stable boy to a position in the estate office under Rodrigo, my grandfathers steward, and everybody was very pleased with his work. So what was he doing here, such a distance from Villaverde?

"

Quick

—tell me—there's nothing the matter with Grandfather?"

"No, no, set your mind at rest; Don Francisco is in good health; at least his

mind

is as active as ever, if his body isn't." For many years my grandfather had been confined to a wheelchair because of rheumatism and wounds from old battles.

"Then why—?"

"He wants you home, and in double-quick time, too. We must leave tomorrow at dawn. Its a bit hard, I must say," grumbled Pedro, "year in, year out, I'm stuck up there on a windy hilltop in the middle of the sierra, not a girl to pass the time of day with, apart from country bumpkins smelling of goats' milk. And when I do get sent to what looks like a decent town, full of jolly señoritas, I'm obliged to turn straight around and gallop home, not even allowed time to buy a gift for Aunt Prudencia."

"You can buy her something tomorrow while I see my tutor.

Why

does Grandfather want me home so urgently?"

"How should I know? A letter came—"

"From France?" My heart leapt—foolishly, I knew.

"No, from Bilbao."

In deep anxiety I asked, "Is it politics?"

Pedro shrugged. "I don't know, I'm telling you! But half an hour later, I was ordered off to fetch you back as fast as the Devil left St. Dunstan's dinner table. The Conde didn't even take time to write you a note."

"Well, he writes so slowly these days, with his stiff hands. But you'd think he could have got Don Jacinto to do it."

"Didn't want Don Jacinto to know, maybe. And I've half killed three mounts on the way," said Pedro, glancing around my room, "and I'm half dead myself. Is there somewhere I can sleep? And I'd not say no to a glass of wine and a mouthful of ham—"

"Of course." I fetched food from a closet and said, "You can have my bed when you're finished. I'll sleep on the floor."

He was scandalized.

"What? You, the Conde's grandson—and an English milord as well—Lord Saint Winnow"—he mouthed the English syllables distastefully—"give up your bed to the

cook's nephew?

"

"Try not to be more of a numbskull than you are," I said, pushing him onto the cot, which was narrow and hard enough, certainly, no ducal couch. "Go to sleep, you're tired out. And I've bedded down in plenty of worse places."

He argued no more, but kicked off his boots. "Beggarly sort of lodgings for a Cabezada," he grunted, looking disparagingly around my small untidy room.

"I like the view. And money's not so plentiful these days.

You

know that."

"Ay, ay. Since our dear king was put back on the throne, with all those French and Russians to hold him there and see he doesn't get pushed off again—"

"

Hush,

you fool!"

"Who could hear, with all that blabber going on outside? And the taxes going up crippling high, and your grandpa's Mexican estates lost in the uprising there—times are bad—" Pedro gave a great yawn and closed his eyes. In two minutes he was asleep.

I pulled my clothes out of the chest, ready for packing, piled them into a heap on the floor, and flung myself down on top of it.

Hours had dawdled by, though, before I slept. It was not the roar of chat from the Plaza Mayor, nor the lumpy layers of shirts and breeches below me, but sheer worry that kept me awake.

Was Grandfather in trouble with the authorities? He made no secret of the fact that he despised King Ferdinand, now back on the Spanish throne, and all the men chosen for his ministers. Villaverde was a tiny, unimportant place, high on the sierra and far from Madrid; but that made no difference. All over Spain men lived in fear these days. My grandfathers crippled condition, his old age, his noble birth and known patriotic fervor, would be no protection. Empecinado, who had bravely led guerrilla troops against Napoleon, had been imprisoned at Roa for ten months, brought out on market days in an iron cage to be spat on by the peasants. A lady of aristocratic family had been put under arrest, simply because she had permitted patriotic songs to be sung in her house. Men had been sent to the galleys at Malaga, just for having Colonel Riego's picture on their walls.

And Riego had been my grandfather's close friend from boyhood.

If Grandfather was in danger of arrest, his future did not bear thinking about.

What could have been in that letter from Bilbao, that caused him to send for me at such racing speed?

***

L

ONG

before daylight, we were up. Seeing me put on my hat and jacket, Pedro said, "I suppose you'll want to say good-bye to your sweetheart?"

I answered rather shortly, "I have no sweetheart in Salamanca."

"Oh, ay," he muttered, "there was that French girl. I forgot. Years ago, that was, though..."

To which I made no reply. Juana was not French, I thought, she was Basque. Pedro, seeing my face, I suppose, smiled his wide apologetic grin—his teeth fanned out like a hand of cards, but the effect was not unpleasing—and said, "I'm sorry, Señor Felix. You know me—I'm a clod. What I say is nothing but nonsense. Would there be any breakfast?"

"Buy yourself what you like." I tossed him a couple of coins. "I have to see my tutor and explain that I shan't be able to attend his classes for a while. I'll not be long—back in twenty minutes."

Having descended the three flights of stairs, I set off running along the Rua Mayor which led to the University.

I found my tutor, as I had expected, already in the classroom where, two hours later, we would assemble for his lecture on the Greek drama. His own lodgings were small and frightfully cold—the pay of a university lecturer was not high—so he often came into the school halls long before dawn.

"Glory be to God!" he exclaimed at the sight of me, hot and panting, "here's one of my students shows real enthusiasm at last! And thankful I am to see ye weren't one of those hotheads who are now cooling their heels in the jail."

He was a small, round-faced, red-haired Irishman, with a soft voice and more learning in him than I would be able to pick up in several lifetimes. His name was Lucius Redmond.

He smiled at me very kindly as I began to gulp out my explanations.

"N-no, sir—I'm afraid it's not—though I

am

enthusiastic—and I would have been out with a placard but I promised my grandfather—the thing is, he has summoned me home, most urgently—"

"Is it the politics?" He gave a quick, wary glance around the ill-lit, empty classroom—at whose battered desks students had been sitting for more than 300 years. Craftsmen built good desks in the sixteenth century!

"I—I can't tell, sir."

"Eh well—let's hope not." He crossed himself. So did I. Politics had closed down the whole University at Salamanca for several years after King Ferdinand returned to Spain from exile, and, when it did reopen, a number of the teachers were missing, and never reappeared. "Give my very kind regards to the Conde," said Dr. Redmond, who had occasionally corresponded with my grandfather on learned subjects. "And return to us as soon as ye can, Felix, dear boy, to take your degree. We'll miss ye, faith, in the classes. Like a sunbeam, ye've been."