44 Scotland Street

Read 44 Scotland Street Online

Authors: Alexander McCall Smith

Tags: #Mystery, #Adult, #Contemporary, #Humour

praise for

ALEXANDER McCALL SMITH

“Utterly enchanting… . It is impossible to come away from an Alexander McCall Smith ‘mystery’ novel without a smile on the lips and warm fuzzies in the heart.”

—Chicago Sun-Times

“McCall Smith’s generous writing and dry humor, his gentleness and humanity, and his ability to evoke a place and a set of characters without caricature or condescension have endeared his books … to readers.” —The New York Times

“Pure joy… . The voice, the setting, the stories, the mysteries of human nature… . [McCall Smith’s] writing is accessible and the prose is beautiful.”

—Amy Tan

“Mr. Smith, a fine writer, paints his hometown of Edinburgh as indelibly as he captures the sunniness of Africa. We can almost feel the mists as we tread the cobblestones.” —The Dallas Morning News

“Alexander McCall Smith has become one of those commodities, like oil or chocolate or money, where the supply is never sufficient to the demand… . [He] is prolific and habit-forming.”

—The Globe and Mail (Toronto)

“[McCall Smith] captures the cold, foggy, historydrenched atmosphere of Edinburgh … with a Jane Austen–like attention to detail.” —USA Today

alexander m

c

call smith

44 SCOTLAND STREET

Alexander McCall Smith is the author of the huge international phenomenon, The No. 1 Ladies’ Detective Agency series, and The Sunday Philosophy Club series. He was born in what is now known as Zimbabwe, and he was a law professor at the University of Botswana and at Edinburgh University. He lives in Scotland.

books by alexander m

c

call smith

in the no. 1 ladies’ detective agency series

The No. 1 Ladies’ Detective Agency

Tears of the Giraffe

Morality for Beautiful Girls

The Kalahari Typing School for Men

The Full Cupboard of Life

In the Company of Cheerful Ladies

in the sunday philosophy club series

The Sunday Philosophy Club

Friends, Lovers, Chocolate

in the portuguese irregular verbs series

Portuguese Irregular Verbs

The Finer Points of Sausage Dogs

At the Villa of Reduced Circumstances

The Girl Who Married a Lion and Other Tales from Africa

44 Scotland Street

44

SCOTLAND

STREET

ALEXANDER McCALL SMITH

Illustrations by

IAIN McINTOSH

anchor books

A Division of Random House, Inc.

New York

FIRST ANCHOR BOOKS EDITION, JUNE

2005

Copyright

©

2005 by Alexander McCall Smith Illustrations copyright

©

2005 by Iain McIntosh

All rights reserved. Published in the United States by

Anchor Books, a division of Random House, Inc., New York. Originally published in Great Britain by Polygon, an imprint

of Birlinn Ltd., Edinburgh, in 2005.

This book is excerpted from a series that originally appeared in the

Scotsman newspaper.

Anchor Books and colophon are registered trademarks of

Random House, Inc.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

McCall Smith, Alexander, 1948–

44 Scotland Street / Alexander McCall Smith ; illustrations by

Iain McIntosh.

p. cm.

eISBN 0-307-27679-1

1. Young women—Fiction. 2. Art galleries, Commercial—

Employees—Fiction. 3. Edinburgh (Scotland)—Fiction.

4. Apartment houses—Fiction. 5. Roommates—Fiction. I. Title:

Forty-four Scotland Street. II. McIntosh, Iain, ill. III. Title.

PR6063.C326A613 2005

823’.914—dc22 2005043627

w w w . a n c h o r b o o k s . c o m

v1.0

This is for Lucinda Mackay

Preface

Most books start with an idea in the author’s head. This book started with a conversation that I had in California, at a party held by the novelist, Amy Tan, whose generosity to me has been remarkable. At this party I found myself talking to Armistead Maupin, the author of T

ales of the City

. Maupin had revived the idea of the serialised novel with his extremely popular serial in

The San Francisco Chronicle.

When I returned to Scotland, I was asked by

The Herald

to write an article about my Californian trip. In this article I mentioned my conversation with Maupin, and remarked what a pity it was that newspapers no longer ran serialised novels. This tradition, of course, had been very important in the nineteenth century, with the works of Dickens being perhaps the best known examples of serialised fiction. But there were others, of course, including Flaubert’s

Madame Bovary

, which nearly landed its author in prison.

My article was read by editorial staff on

The Scotsman

, who decided to accept the challenge which I had unwittingly put down. I was invited for lunch by Iain Martin, who was then editor of the paper. With him at the table were David Robinson, the books editor of the paper, Charlotte Ross, who edited features, and Jan Rutherford, my press agent. Iain looked at me and said: “You’re on.” At that stage I had not really thought out the implications of writing a novel in daily instalments; this was a considerable departure from the weekly or monthly approach which had been adopted by previous serial novelists. However, such was the air of optimism at the lunch that I agreed.

The experience proved to be both hugely enjoyable and very instructive. The structure of a daily serial has to be different from that of a normal novel. One has to have at least one development in each instalment and end with a sense that something more may happen. One also has to understand that the readership is a newspaper readership which has its own very special characteristics.

The real challenge in writing a novel that is to be serialised in this particular way – that is, in relatively small segments – is to keep the momentum of the narrative going without becoming too staccato in tone. The author must engage a reader whose senses are being assailed from all directions – from other things on the same and neighbouring page, from things that are happening about him or her while the paper is being read. Above all, a serial novel must be entertaining. This does not mean that one cannot deal with serious topics, or make appeal to the finer emotions of the reader, but one has to keep a light touch.

When the serial started to run, I had a number of sections already completed. As the months went by, however, I had fewer and fewer pages in hand, and towards the end I was only three episodes ahead of publication. This was very different, then, from merely taking an existing manuscript and chopping it up into sections. The book was written while it was being published. An obvious consequence of this was that I could not go back and make changes – it was too late to do that.

What I have tried to do in

44 Scotland Street

is to say something about life in Edinburgh which will strike readers as being recognisably about this extraordinary city and yet at the same time be a bit of light-hearted fiction. I think that one can write about amusing subjects and still remain within the realm of serious fiction. It is in observing the minor ways of people that one can still see very clearly the moral dilemmas of our time. One task of fiction is to remind us of the virtues – of love and forgiveness, for example – and these can be portrayed just as well in an ongoing story of everyday life as they can on a more ambitious and more leisurely canvas.

I enjoyed creating these characters, all of whom reflect human types I have encountered and known while living in Edinburgh. It is only one slice of life in this town – but it is a slice which can be entertaining. Some of the people in this book are real, and appear under their own names. My fellow writer, Ian Rankin, for example, appears as himself. He said to me, though, that I had painted him as being far too well-behaved and that he would never have acted so well in real life. I replied to him that his self-effacing comment only proved my original proposition. Then there are some who appear as themselves, but have no speaking part. That great and good man, Tam Dalyell, does that. We see him, but we do not hear what he says. We also see mention of another two admirable and much-liked public figures, Malcolm Rifkind and Lord James Douglas Hamilton, who flit across the page but who, like Mr Dalyell, remain silent. Perhaps all three of them could be given a speaking part in a future volume – if they agree, of course.

I enjoyed writing this so much that I could not bear to say goodbye to the characters. So that most generous paper,

The Scotsman

, agreed to a second volume, which is still going strong, day after day, even as I write this introduction to volume one. In the somewhat demanding task of writing both of these volumes, I have been sustained by the readers of the paper, who urged me on and provided me with a wealth of suggestions and comments. I feel immensely privileged to have been able to sustain a long fictional conversation with these readers. One reader in particular, Florence Christie, wrote to me regularly, sometimes every few days, with remarks on what was happening in

44 Scotland Street

. That correspondence was a delight to me and helped me along greatly in the lonely task of writing. I also had most helpful conversations with Dilly Emslie, James Holloway and Mary McIsaac. Many others – alas, too numerous to mention – have written to me or spoken to me about the development of characters and plot. To all of these I am most indebted. And, of course, throughout the whole exercise I had the unstinting daily support of Iain Martin and David Robinson of

The Scotsman

. I was also much encouraged by Alistair Clark and William Lyons of the same newspaper.

But the most important collaboration of all has been with the illustrator of this book, Iain McIntosh. Iain and I have worked together for many years. Each year for the last twenty years or so I have written a story at the end of the year which has been printed for private circulation by Charlie Maclean and illustrated by Iain. Iain then illustrated my three novels in the

Portuguese Irregular Verbs

series. His humour and his kindness shine out of his illustrations. He is the modern John Kay, and Edinburgh is fortunate to have him to record its face and its foibles.

Alexander McCall Smith, January 2005

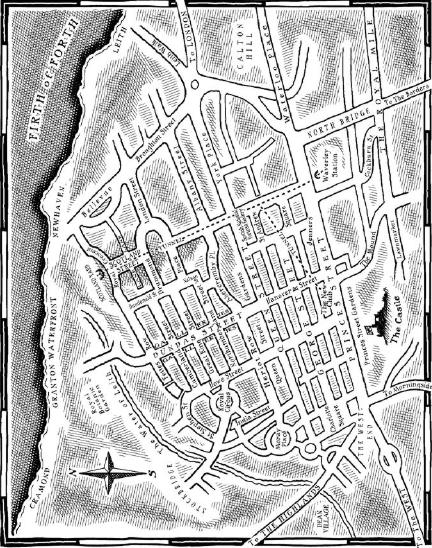

Central Edinburgh