59 Seconds: Think a Little, Change a Lot (23 page)

Read 59 Seconds: Think a Little, Change a Lot Online

Authors: Richard Wiseman

Tags: #Psychology, #Azizex666, #General

LOWER YOUR BLOOD PRESSURE BY DOING NOTHING

A few years ago I conducted an experiment into the psychology of alcohol consumption as part of a television program. The study involved a group of students spending an evening in a bar with their friends. It was easy to persuade people to participate because the drinks were on the house. The only downside was that throughout the course of the evening our guinea pigs were asked to take a few short tests. On the night of the experiment, everyone arrived and the first round of testing began. Each student was presented with a list of numbers and asked to remember as many as possible, walk along a line marked on the floor, and undergo a reaction-time test that involved the experimenter’s dropping a ruler from between her first finger and thumb and asking the students to catch it the moment they saw it move.

Having completed the initial tests, we quickly moved on to the desirable part of the evening—drinking. Each student was randomly assigned to a blue group or a red group, given

an appropriate badge, and told that they were more than welcome to make good use of the free bar. There was, however, just one rule—each person had to go to the bar and order their own drink, and no one was to get any drinks for friends. Throughout the evening, we frequently interrupted the flow of conversation, pulling people away for testing and having them perform the same memory, balance, and reaction tests as before.

As the amount of alcohol flowing through their veins increased, people became much louder, significantly happier, and far more flirtatious. The test results provided an objective measure of change, and by the end of the evening most people had to struggle to recall any list of numbers that contained more than one digit, consistently failed even to find the line marked on the floor, and closed their fingers a good sixty seconds after the ruler had clattered to the ground. Okay, so I am exaggerating for comic effect, but you get the idea. By far the most fascinating result, however, was the similarity in scores between those wearing red badges and those wearing blue, because both groups had been deliberately duped.

Both groups seemed to suffer significant memory impairment, experience increased difficulty balancing on the line, and constantly let the ruler slip through their fingers.

But what the students in the blue group didn’t know was that they hadn’t touched a drop of alcohol throughout the entire evening. Before the experiment started, we had secretly stocked half of the bar with drinks that contained no alcohol but nevertheless looked, smelled, and tasted like the real thing. The bar staff had been under strict instructions to look at the color of each person’s badge and provide those in the red group with genuine alcohol and those in the blue group with the nonalcoholic fakes. Despite the fact that not a single drop of liquor had passed their lips, those with blue badges managed

to produce all of the symptoms commonly associated with having a few too many. Were they faking their reactions? No. Instead, they were convinced that they had been drinking, and that thought was enough to convince their brains and bodies to think and behave in a “drunk” way. At the end of the evening we explained the ruse to the blue group. They laughed, instantly sobered up, and left the bar in an orderly and amused fashion.

This simple experiment demonstrates the power of the placebo. Our participants believed that they were drunk, and so they thought and acted in a way that was consistent with their beliefs. Exactly the same type of effect has emerged in medical experiments when people exposed to fake poison ivy developed genuine rashes, those given caffeine-free coffee became more alert, and patients who underwent a fake knee operation reported reduced pain from their “healed” tendons. In fact, experiments comparing the effects of genuine drugs as compared to those of sugar pills show that between 60 percent and 90 percent of drugs depend, to some extent, on the placebo effect for their effectiveness.

21

Exercise is an effective way to reduce blood pressure, but how much of this relationship is just in the mind? In a groundbreaking and innovative study, Alia Crum and Ellen Langer at Harvard University enlisted the help of more than eighty hotel room attendants selected from seven hotels.

22

They knew that the attendants were a physically active lot. They cleaned and serviced an average of fifteen rooms each day, with each room taking about twenty-five minutes, and they were constantly engaging in the type of lifting, carrying, and climbing that would make even the most dedicated gymgoer green with envy. However, Crum and Langer speculated that even though their attendants were leading an active life, they might not realize that this was the case; the researchers

wondered what would happen if the attendants were told how physically beneficial their job was for them. Would they come to believe that they were fit people, and could this belief cause significant changes in their weight and blood pressure?

The research team randomly allocated the attendants in each hotel to one of two groups. Those in one group were informed about the upside of exercise and told the number of calories they burned during a day. The experimenters had done their homework, and so they could tell the attendants that a fifteen-minute sheet-changing session consumed 40 calories, that the same amount of time vacuuming used 50, and that a quarter of an hour scrubbing a bathroom used 60 more calories. So that the information would stick in their minds, everyone in the group was given a handout containing the important facts and figures, and the researchers placed a poster with the same information on a bulletin board in the staff lounge. The control group of attendants was also given the general information about the benefits of exercise, but they were not told about the calories they themselves burned. Everyone then completed a questionnaire about how much they tended to exercise outside of work, their diet, and drinking and smoking habits. They also took a series of health tests.

A month later the researchers returned. The hotel managers confirmed that the workloads of the attendants in the “wow, your job involves lots of exercise” group and the control group had remained constant. The experimenters then asked everyone to complete the same questionnaires and health tests as before, and set about analyzing the data.

The two groups had not taken additional exercise outside of work, and neither had they changed their eating, smoking, or drinking habits. As a result, there were no actual changes in their lifestyle that would suggest that one group should have become fitter than the other.

The researchers turned their attention to the health tests. Remarkably, those who had been told how many calories they burned on a daily basis had lost a significant amount of weight, lowered their body mass index and waist-to-hip ratio, and experienced a decrease in blood pressure. The control group attendants showed no similar improvements.

So what caused this health boost? Crum and Langer believe that it is all connected to the power of the placebo. By reminding the attendants of the amount of exercise that they were getting on a daily basis, the researchers altered the attendants’ beliefs about themselves, and their bodies responded to make these beliefs a reality. It seems that in the same way people slur their words when they think they are drunk, or develop a rash when they think they are ill, so merely thinking about their normal daily exercise can make them healthier.

Whatever the explanation for this mysterious effect, when it comes to improving your health, you may already be putting in the necessary effort. It is just a case of realizing that.

IN 59 SECONDS

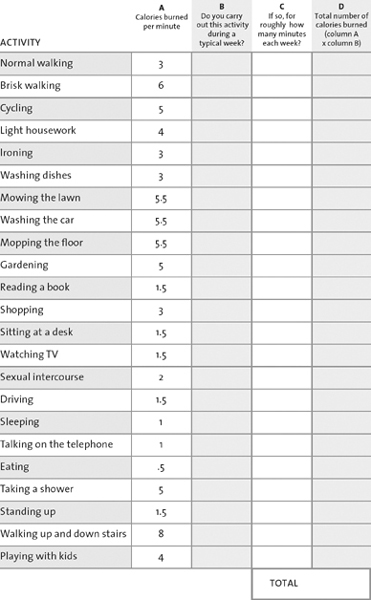

Crum and Langer’s research is controversial but, if valid, suggests that being conscious of the fuel-burning activities that you engage in every day is good for you. The following chart gives an approximate number of calories burned by someone of average weight carrying out a range of normal activities (people with higher or lower weight will burn proportionately more or fewer calories). Use the chart to calculate the approximate number of calories you burn each day.

Keep the chart handy to remind yourself of the “invisible” exercise that you get each day of your life, and according to the theory, you should see your stress level drop by doing nothing.

decision making

Why

two heads

are no better than one,

how never to

regret

a decision again,

protect

yourself against

hidden

persuaders,

and

tell

when someone is

lying

to you

WHEN PEOPLE HAVE

an important decision to make in the workplace, they often arrange to discuss the issues with a group of well-informed and levelheaded colleagues. On the face of it, that seems a reasonable plan. After all, when you’re making up your mind, it is easy to imagine that consulting people with a variety of backgrounds and expertise could provide a more considered and balanced perspective. But are several heads really better than one? Psychologists have conducted hundreds of experiments on this issue, and their findings have surprised even the most ardent supporters of group consultations.

Perhaps the best-known strand of this work was initiated in the early 1960s by MIT graduate James Stoner, who examined the important issue of risk taking.

1

It will come as no great surprise that research shows that some people like to live life on the edge, while others are more risk averse. However, Stoner wondered whether people tended to make more (or less) risky decisions when they were part of a group. To find out, he devised a simple but brilliant experiment.

In the first part of his study, Stoner asked people to play the role of a life coach. Presented with various scenarios in which someone faced a dilemma, they were asked to choose which of several options offered the best way forward. Stoner had carefully constructed the options to ensure that each represented a different level of risk. For example, one scenario was about a writer named Helen who earned her living writing cheap

thrillers. Helen had recently had an idea for a novel, but to pursue the idea she would have to put her cheap thrillers on the back burner and face a decline in income. On the positive side, the novel might be her big break, for which she could earn a large amount of money. On the downside, the novel might be a complete flop, and she would have wasted a great deal of time and effort. Participants were asked to think about Helen’s dilemma and then indicate how certain she should be that the novel was going to be a success before she gave up her regular income from the cheap thrillers.

If a participant was very conservative, they might indicate that Helen needed to be almost 100 percent certain. If the participant felt much more positive about risk, they might indicate that even a 10 percent likelihood of success was acceptable.

Stoner then placed participants in small groups of about five people each. The groups were told to discuss the scenarios and reach a consensus. His results clearly showed that the decisions made by groups tended to be far riskier than those made by individuals. Time and again, the groups would advise Helen to drop everything and start work on the novel, while individuals would urge her to stick with writing thrillers. Hundreds of further studies have shown that this effect is not so much about making riskier decisions per se but about polarization. In Stoner’s classic studies, various factors caused the group to make riskier decisions, but in other experiments groups have become more conservative than individuals alone. In short, being in a group exaggerates people’s opinions, causing them to make a more extreme decision than they would on their own. Depending on the initial inclinations of individuals in the group, the final decision can be extremely risky or extremely conservative.

This curious phenomenon has emerged in many different situations, often with worrisome consequences. Gather a group

of racially prejudiced people, and they will make even more extreme decisions about racially charged issues.

2

Arrange a meeting of businesspeople who are open to investing in failing projects, and they will become even more likely to throw good money after bad.

3

Have aggressive teenagers hang out together, and the gang will be far more likely to act violently. Allow those with strong religious or political ideologies to spend time in one another’s company, and they will develop more extreme, and often violent, viewpoints. The effect even emerges on the Internet, with individuals who participate in discussion lists and chat rooms voicing more extreme opinions and attitudes than they normally would.

What causes this strange but highly consistent phenomenon? Teaming up with people who share your attitudes and opinions reinforces your existing beliefs in several ways. You hear new arguments and find yourself openly expressing a position that you may have only vaguely considered before. You may have been secretly harboring thoughts that you believed to be unusual, extreme, or socially unacceptable. However, when you are surrounded by other like-minded people, these secret thoughts often find a way of bubbling to the surface, which in turn encourages others to share their extreme feelings with you.