97 Orchard: An Edible History of Five Immigrant Families in One New York Tenement (19 page)

Read 97 Orchard: An Edible History of Five Immigrant Families in One New York Tenement Online

Authors: Jane Ziegelman

Tags: #General, #Cooking, #19th Century, #History: American, #United States - State & Local - General, #United States - 19th Century, #Social History, #Lower East Side (New York, #Emigration & Immigration, #Social Science, #Nutrition, #New York - Local History, #New York, #N.Y.), #State & Local, #Agriculture & Food, #Food habits, #Immigrants, #United States, #Middle Atlantic, #History, #History - U.S., #United States - State & Local - Middle Atlantic, #New York (State)

According to government records, 1,028,588 Jews immigrated to the United States between 1900 and 1910. Of that number, the great majority came from the “Pale of Jewish settlement,” a geographic designation created by Catherine the Great in 1791. Catherine established the Pale in an effort to corral and isolate the Jews living within the newly expanded Russian Empire. On a map, the territory corresponds to modern-day Ukraine, Poland, Latvia, Lithuania, Moldova, and Belarus. Russian Jews were well acquainted with anti-Semitism, but the Jewish mass migration that began in the 1880s was sparked by a wave of pogroms that heightened the Jews’ perennial status as outsiders. They began in 1881 in what is now Ukraine, as rioting mobs destroyed millions of rubles’ worth of Jewish property, killing dozens of Jews in the process. Small-scale pogroms continued for the next twenty years, erupting in full force in the city of Kishinev on Easter Day, 1903, when fifty Jews were killed during several days of uncontrolled violence. America promised Jews a safe harbor and political and religious freedom, along with unbounded economic opportunity.

Russian and Eastern European Jews lived primarily in small market towns known as shtetlach. Once a week, Gentile farmers from the surrounding countryside would converge on the shtetl to sell their goods and buy supplies from the Jewish shopkeepers, though shtetl Jews worked in many other occupations as well. The distinct folk culture that developed in the shtetlach found expression in language, music, and religion. Unlike their German brothers and sisters, shtetl Jews practiced an unambiguously traditional version of Judaism. Where men expressed their piety through study and prayer, women spoke through the language of food. The sacred responsibility of the shtetl homemaker was to keep a kosher home, celebrating the holidays with all the required ritual dishes. On the Sabbath, and other holy days, she distributed food to the poor. Landing on Ellis Island, these same Jews found a profusion of food, but, with a few exceptions, none of it was kosher.

Actually, the Jews’ culinary problems started at sea. Though the steamship companies were legally obliged to feed their passengers, only a fraction served kosher meals. Some fulfilled the requirement with a single food: herring. Others went through the trouble of installing kosher kitchens but hired cooks who were kashruth-illiterate, unfamiliar with the full sweep of Jewish dietary law. Jewish travelers who knew what to expect traveled with their own survival rations. One very common food was thick slices of zwieback-like bread that had been dried in the oven to keep it from spoiling. Travelers also preserved their bread by dipping it in vinegar and sugar then baking it. For protein, they packed dried fish and salami. The chief problem with home-packed food was that it often ran out before the ship reached America, leaving the immigrant with nothing but water and perhaps some tea for the last leg of the journey. Between the rampant seasickness and the germ-infested quarters, no one in steerage—Jew or Gentile—fared particularly well. The Jews, however, faced the added challenge of finding kosher nourishment, an often impossible task, and many arrived at Ellis Island stooped with exhaustion, colorless, and malnourished. Unfortunately for them, the relief of standing on solid ground was quickly followed by another realization: there was still nothing to eat.

The one place freshly landed Jews could find nourishment was at the Ellis Island lunch stand, which carried tinned sardines and kosher sausages. But the stand was only accessible to Jews who had already passed inspection. For Jews detained on the island, the food situation was grim. There was nothing kosher about the immigrants’ dining room, which left devout Jews with a choice: they could either go hungry and possibly starve, or break the food commandments and eat. (The Rogarshevsky family faced this precise dilemma in 1901, though only briefly.) The one time of year Jews were assured of a good kosher meal was at Passover, the springtime feast commemorating the Hebrew exodus. Under the headline “Passover at Ellis Island,” in 1904, the

New York Times

ran this short but evocative story on the immigrants’ seder:

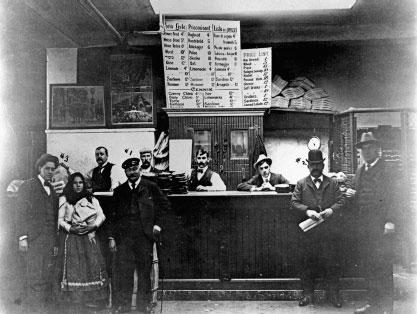

The food counter at Ellis Island, 1901.

“Food counter in railroad ticket department at Ellis Island,” Terence Vincent Powderly Photographic Prints, The American Catholic History Research Center and University Archives, The Catholic University of America, Washington, D.C.

The Feast of the Passover was celebrated in due form last night at Ellis Island by 300 Jewish immigrants, detained there awaiting inspection. Commissioner Williams gave them permission to celebrate the rites of their church and the great dining hall was turned over to them, and there, dinner was served in keeping with the occasion.

The tables were covered with snowy linen and new dishes right from the storeroom. In the kitchen, the utensils were all new, and the dinner was cooked under the supervision of the immigrants themselves. The dinner was rather more sumptuous than is usually served to incomers—chicken soup, roast goose and apple sauce, mashed potatoes, ground horseradish, matzoth, black tea, and oranges.

5

A gastronomic retelling of the Jews’ escape from slavery, the Passover meal held special significance for the immigrants. The parallels were perfectly clear: Russia was their Egypt, the czars were their pharaohs, while America was their modern-day Canaan. But Passover came just once a year.

Relief for the kosher food drought on Ellis Island arrived in 1911, when the Hebrew Immigrant Aid Society finally convinced the authorities to give the depot its own kosher kitchen. HIAS, as it was known, was just one of the many immigrant aid societies with offices on Ellis Island, each one serving the needs of a particular ethnic or national group. Founded on the Lower East Side in 1902, HIAS was formed with a single mandate: to provide any Jew unlucky enough to die on Ellis Island with a proper Jewish burial. From that narrow focus, the mission quickly broadened to helping new arrivals gain a firm foothold in their adopted country. HIAS representatives wearing blue caps with the HIAS acronym embroidered in Yiddish met the incoming ferries and distributed pamphlets (also in Yiddish) on the inspection process. They helped steer immigrants through the island’s bureaucratic maze and advocated for immigrants condemned to return to “the country from whence they came.”

From their vantage point on Ellis Island, it was plain to the HIAS workers that the kosher-food shortage diminished the immigrant’s chance of passing inspection. The Ellis Island doctors sorted all new arrivals into classes, admitting most but barring anyone with tuberculosis, epilepsy, or any other “loathsome and dangerous disease.” In their decrepit post-voyage state, a high percentage of Jews fell into the catchall category “LOPD,” bureaucratic shorthand for “lack of physical development.” It was a vague diagnosis, and not especially loathsome, but serious enough to block the immigrant from entering the country. The reason was purely economic. According to the Ellis Island calculus, physical weakness diminished the individual’s earning power, a most serious consideration. Along with “pauper,” the single largest class of unwanted foreigners, the languishing Jews were officially rejected with another catchall label, LPC, or “likely to become a public charge,” when all they really needed was a few square meals and a good night’s rest.

In 1911, a New Yorker named Harry Fishel took this argument to Washington and presented it to President Taft. An immigrant himself, Fishel was a Donald Trump–like figure who made his fortune in the New York real estate market, purchasing and developing large tracts of land. Many of his holdings were on the Lower East Side, including one entire block of tenements on Jefferson Street. Fishel was also an Orthodox Jew who had channeled his wealth into yeshivas, hospitals, and assorted charities, including HIAS, where he served as treasurer for over half a century.

Harry Fishel’s crusade to feed the immigrants was doubly motivated. An act of compassion on behalf of the helpless foreigner, it was also an act of self-preservation. The way Fishel saw things, the kosher-food predicament on Ellis Island served as a roadblock to the kind of Jews America needed most, the rabbis and scholars who were so essential to the future survival of Orthodox Judaism in secular America. Here was a cause the mogul was ready to fight for. Face-to-face with the president, Fishel pleaded his case with the urgency of a condemned man. He returned to New York the following day with a firm pledge that the United States government would do what it could to fill the kosher gap.

The food served in the kosher dining room was instantly recognizable to the immigrant palate. There were kippered herring, noodle and potato kugels, barley soup, and dill pickles. American specialties also made regular appearances. The following menus from 1914 are the earliest on record:

MONDAY

BREAKFAST:

Boiled eggs (2)

Bread and butter

Coffee

DINNER:

Potato soup

Hungarian goulash

Vegetables

Bread

SUPPER:

Pickled herring

Fresh fruit

Bread and butter

Tea

TUESDAY

BREAKFAST:

Fresh fruit

American cheese

Bread and butter

Coffee

DINNER:

Vegetable soup

Pot roast

Potatoes

Bread

SUPPER:

Bologna

Dill pickles or sauerkraut

Stewed fruit

Bread and tea

WEDNESDAY

BREAKFAST:

Fruit

American sardines

Bread and butter

Coffee

DINNER:

Barley soup

Roast meat

Vegetables

Bread

SUPPER:

Beans (baked by Mrs. Paley)

Cakes

Bread and tea

6

The size of the crowd in the dining room rose and fell depending on that day’s shipping schedule. The room might be empty for breakfast, but if a ship arrived that afternoon filled with Russians or Hungarians or Poles, the kosher kitchen went into high alert, capable of feeding six hundred mouths at a single sitting. One interesting footnote to the Ellis Island kitchen’s history is the leading role played by women. During World War I, a woman known to us only as Mrs. Paley (first initial “S”) was in charge, but in later years the job of head cook fell to another woman, whom we know much more about.

When Sadie Schultz came to work on Ellis Island in 1929, she was forty-six years old with a long culinary résumé. Born in Canada in 1882, Sadie Citron Schultz was the daughter of Polish immigrants who had returned to Europe when Sadie was still a young girl and then re-emigrated to the United States, settling on the Lower East Side. According to family legend, Sadie’s mother earned the family’s passage working as a cook for one of the steamship companies, which helps explain the zigs and zags in their route to America. The young Sadie Schultz entered the New York food economy at twelve years old with a waitressing job in an East Side restaurant. She worked steadily from that point on, with only two interruptions. The first was in 1906, the second in 1910, the years her children were born. As soon as the babies were old enough, she put them into the free nursery at the Educational Alliance on East Broadway and returned to the restaurant. At some point in her career, she traded in waitressing for a job behind the stove, and this is where she remained for the rest of her professional life.