A 1950s Childhood (3 page)

Authors: Paul Feeney

In the 1950s, a radiogram like this would be considered a real status symbol.

This popular style of television was described as a ‘slim television’ in the late 1950s, and was suitable for any size room.

There had been vegetarians in Britain for over a hundred years, but they must have been very small in number back in the ’50s, and it is unlikely there were any among post-war working-class families. The austere 1950s didn’t really cater for people with dietry preferences. People generally ate what was available, and meat was considered to be a necessary source of protein and essential nutrients for healthy growing children and working adults. Kids were very active and used up lots of energy. They needed feeding and, in the main, they were given what was thought to be good for them rather than what they liked. It was considered important to have three square meals a day, and when money was scarce you would fill up on bread and potatoes.

What you had for breakfast was usually dependent upon what you could afford, and whether your mum worked and how much time she had to prepare it. During the week, most kids would have cereal, porridge, or a lightly boiled egg with bread soldiers to dip in. A full breakfast or ‘fry-up’ was usually reserved for the weekend when, if you could afford it, breakfast became a real meal, with bacon, egg, sausage, tomatoes, baked beans, and black pudding with fried bread. Everything except the baked beans was fried. There was always a fresh pot of tea being made. It was tea with everything; it was just second nature and coffee was too expensive to drink regularly throughout the day.

For main meals there were lots of stews and homemade meat pies, always with loads of potatoes and fresh ‘in season’ vegetables. You were always made to eat everything on your plate – ‘eat your greens up or you won’t grow’. Everyone that could afford it had a traditional roast dinner on Sunday, with roast beef, pork or lamb and roast potatoes, and loads of vegetables and gravy. Chicken was too expensive and usually reserved for Christmas. Sunday’s leftovers were served up on Monday and Tuesday in the form of stew, meat pie, or cold meat dishes. During the rest of the week you would have a variety of wholesome dishes for dinner, including liver and bacon, bangers and mash, lamb or pork chops, egg and chips, toad-in-the-hole, bubble and squeak, and fish and chips on Fridays. There was always plenty of bread on the table to fill up on and a jug of water to wash it all down.

In summer, there were boring cold meat salads to contend with, only made tolerable by lashings of salad cream. So much adventure playtime was wasted while stuck indoors

and pushing a piece of cucumber or cold lettuce around on your plate.

Puddings, sweets or ‘afters’, as they were often called, were usually a luxury reserved for Sundays. Rice pudding, bread and butter pudding, and semolina or tapioca milk puddings – you either loved them or hated them! Homemade spotted dick or apple pie served with Bird’s yellow custard with the skin on top, or if you were really posh you might have pink blancmange. Pineapple chunks with Carnation milk, jelly and ice cream, trifle, and the occasional luxury of a block of Neapolitan ice cream.

A large slab of Lard cooking fat was ever present in the 1950s kitchen. It seemed to be a part of every mum’s essential cooking ingredients. It went into everything – pies, cakes, bread, and biscuits – nothing was spared from a good chunk of Lard. It was even spread on bread as an alternative to butter, but it could never quite compare to the delicious taste of homemade beef or pork dripping, which was formed from the fat and liquid that was left in the pan after mum had cooked a joint of beef or pork. And who can forget the scrumptious taste of fish and chips cooked in beef dripping?

Welsh rarebit! Although often referred to as Welsh rarebit, in most households it was usually just a basic cheese on toast, made with plain cheddar cheese. No fancy Welsh rarebit recipes needed to entice a hungry child to eat it as a teatime or supper snack. On the other hand, there was nothing more likely to cause the sudden loss of appetite than the sight of a curled-up Spam sandwich being pushed in your direction across the table. Spam was a cheap substitute for ham but it was mystery meat; the colour, texture and taste

didn’t resemble real ham. It was a type of processed meat, made mostly from pork, but you were never quite sure what Spam was! Could there be a child of the ’50s who actually liked the stuff?

Other popular sandwich fillings included such diverse things as mashed potatoes, chips, bananas, jam, salad cream, cheese, and of course fish paste, the ingredients of which was another childhood mystery!

The growth in ownership of modern-day household appliances was seriously hindered by the economic impact of the Second World War on Britain’s consumer market. As was the case with most labour-saving devices for the home, we were well behind the United States, where a large majority of homes already had an electric washing machine. In the late 1950s, less than a third of households in Britain had a washing machine, and these were single tub, top-loading machines, with a wringer on top. Most people were still washing by hand, using a scrubbing brush, washboard, and a hand-operated mangle. There were launderettes, but they were few and far between, and they were also expensive to use. In the cities and larger towns, there were laundry shops where people would take their dirty white cotton clothes, towels and bed sheets to be washed by machine. These places were called the ‘bagwash’, because you would put all your dirty stuff inside a heavy-duty cloth bag and then take the bag to the shop, where it would be weighed and tagged with a piece of cloth that

was indelibly marked with your name or code number. The ‘bagwash’ was usually just an empty shop with a small counter, and a large set of scales that sat on the bare wooden floorboards. After your bag had been tagged, the lady behind the counter would heave it onto a stack of other bags that were piled high against the back wall of the shop, where they would all stay until the laundry van collected them later in the day. Some ‘bagwash’ shops only opened one day a week for dropping off washing, and another day for collecting it. These would be known as the ‘bagwash’ days for the local area. When your mum collected the bagwash it would smell of chemicals and still be damp, just right for mum’s favourite job – ironing. You only took white cotton things to the ‘bagwash’ because everything was bleached and boiled in the laundry – bed mites didn’t stand a chance!

It was a time when many people felt at ease to leave the street door on the latch, except at night or if the house was empty, and they would leave a key hanging down behind the letterbox just in case someone did get locked out. Apart from the noise of kids playing, the streets were usually fairly quiet places and so not much went unnoticed. There were the regular well-known deliverymen like the postman, milkman, breadman, coalman, and of course ‘the man from the Pru’. Everyone seemed to have the Prudential Insurance man call each week to collect the small life insurance premiums. Before the age of telesales,

when most people didn’t even have a telephone, the door-to-door salesmen were very active. The tallyman would call door-to-door selling goods on the never-never. They were so convincing – ‘you can have all this for just a shilling a week!’ It really is true that some people would hide behind the sofa when he knocked on the door for his money. Many of the inner-city travelling salesmen would ride pushbikes, and some used the earliest mopeds, which were just basic pushbikes with a small motor attached to the top of the front tyre. There was a profusion of brush and cleaning equipment salesmen, and of course the ever popular and very convincing

Encyclopaedia Britannica

salesmen, offering the whole twenty-four-volume set of encyclopaedias on an easy payment plan. No child could hope to pass the eleven-plus exams without access to their very own set of encyclopaedias.

Postmen always looked smart with their top-to-toe uniform, which included a shirt and tie, a lapel badge carrying the postman’s number, and a flat ‘military style’ peaked cap with a badge that featured a post horn and St Edward’s crown. The post would drop through the letterbox at about 7am each day and there would be a second delivery later in the morning.

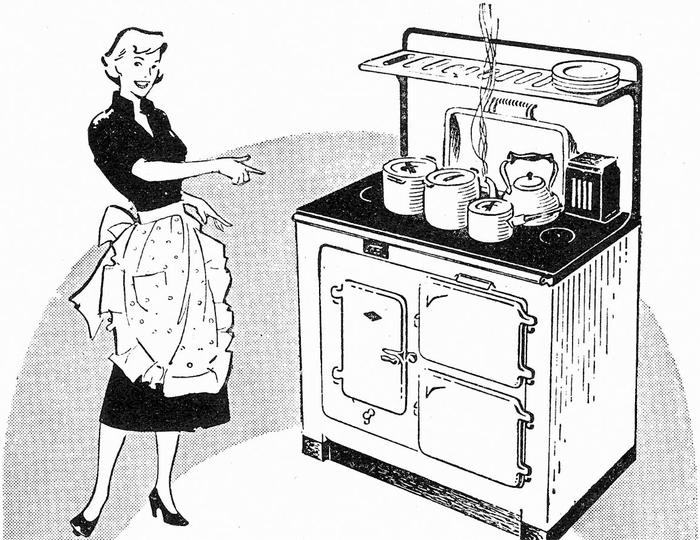

In 1953, this latest Esse cooker with boiler cost

£

91 4s 6d. Equivalent to about

£

1,900 at today’s values based on the retail price index.

The telegram boy, in his navy blue uniform with red piping and pillbox cap, was never a welcome sight in the street. Few people had telephones and the fastest way to get a message to someone was by telegram, but they were expensive to send (about 6d for nine words and a penny for each additional word, including the address) and were only used to send urgent messages of joy, sorrow and success. Although they were traditionally sent to announce or

congratulate expected good news, like a marriage or the birth of a child, in everyday life they usually meant bad news, normally a death. The curtains would twitch whenever a telegram boy arrived in the street, and everyone’s pulses would race like mad.

The milkman also wore a uniform, including a collar and tie and a peaked cap. The milk was delivered from either a horse-drawn milk cart or a hand-pulled milk float, also known as a pedestrian-controlled float. Each morning, the

milk magically arrived on your doorstep before you had even poked your head out from the bedclothes.

Outlying areas would have groceries and bread delivered, and sometimes the milk would be delivered from an urn into your own jug and measured by the pint or half pint. Quite often these delivery rounds-men would become friends with their customers, downing many a cup of tea en route.

Coal was delivered regularly on horse-drawn drays or trucks. The coalmen were usually large intimidating men with faces and hands blackened by the coal dust. They often wore flat caps and sleeveless leather jackets. The coalmen would heave the huge hundredweight (cwt) sacks of coal off the flatbed dray and carry them on their backs to the coalbunkers, or tip them through a coalhole in the pavement into the cellar below.

Chimney sweeps were always a source of entertainment for kids. They would usually arrive on a pushbike carrying a few long-handled brushes and an old sheet. The sweep would have a permanent covering of soot all over, even when he had just arrived. All the furniture would be pushed back from the fireplace and covered with sheets before he arrived, but it was always a traumatic experience for house-proud mums. For the kids, it was amusing to watch mum’s face and to hear her gasp as the sweep manoeuvred his brushes up the chimney and a cloud of soot bellowed out from beneath the protective sheet, dispensing a nice covering of black dust around the room. The sweep would always be carefully escorted from the house when he had finished to make sure he didn’t rub up against anything he passed on the way. Then the clean-up would begin! In the 1950s, people were encouraged by the government to

use smokeless fuel to help reduce the smog. Some people started to board up their fireplaces and fit new snazzy two-bar electric fires to replace the old coal fire. Some did it to be fashionable, but most did it to get rid of the mess and inconvenience of fetching the coal in from the cold cellar or outside bunker.