A Companion to the History of the Book (80 page)

Read A Companion to the History of the Book Online

Authors: Simon Eliot,Jonathan Rose

In the twentieth century, another collector, a contemporary and friend of John Johnson, brought together a major collection of American and European printed ephemera spanning a period from 1856 to the 1970s. Bella Landauer began gathering material in 1923 when she started collecting book plates. Her interests and obsessions quickly expanded to trade cards, advertising, and eventually all genres of material. Over 8,000 items were given to the New York Historical Society and now form the Bella Landauer Collection of Business and Advertising Ephemera. She also donated ephemera to many other national institutions.

Collections such as these provide serendipitous sources of information for the book historian. More comprehensive sources are publishers’ archives: much can be gleaned from the ephemeral material they contain. The development of publishers can partly be traced through letterheads, detailing moves to new premises and the coming and going of partners and directors, quite apart from the contents of such letters and bills. Prospectuses and announcements are an obvious source of information about publications but can also give an overview of the philosophy and aspirations of a publishing enterprise – occasionally they become a manifesto. When Harold Midgley Taylor set up the Golden Cockerel Press in 1920, he outlined the aims and ideals of his literary and printing cooperative:

Its members are their own craftsmen, and will produce their own books themselves in their own communal workshops … By their elimination of the middleman they are able to stake their work as printer-publishers on an artistic success in exactly the same way that an honest author stakes his. Wherever such an arrangement is possible, they are therefore willing, after the necessary outlay of paper and publicity has been paid off, to share the gross receipts with the author, without any separate payment for their work as printers. Except in the case of very large books and very short runs, the shares will be equal. This seems to be the only way in which the literary artist can get any adequate or fair remuneration for his work … As regards distribution, they base their method on Reputation rather than Publicity. They believe that a good piece of work has its natural public … They propose as a rule to dispense with travelers … They will use the word advertisement in its old sense of announcement and not eye-trap, announcing their publications regularly and adequately … (Golden Cockerel Press announcement 1920, John Johnson Collection, Bodleian Library, Oxford)

From such documents – and from publicity material, notices to travelers, catalogues, and the myriad of other trivial documents generated by a publisher – one can piece together the story of the firm and the stories of the books produced.

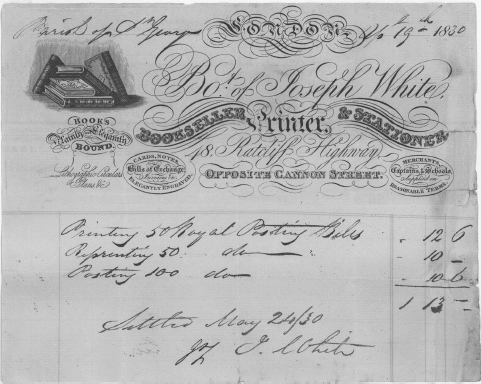

Ephemera can also provide first-hand evidence of the history of printing. Printers’ advertisements and letterheads naturally boast of new processes and equipment: the adoption of lithography, photography, stereotyping, electrotyping, process engraving, Monotype, and Linotype can be dated by noting the appearance of such terms. Invoices, bills, and receipts can provide details of costings and profit margins (

figure 32.3

). The other trades and industries associated with book production, such as paper manufacturers and binders, also printed informative ephemera of a similar nature.

Many documents are generated during the production of a book: proofs, layouts, specifications, artwork, and design visuals. These documents are ephemeral as they only have value for a short time in production: once the book is published they become redundant and are often destroyed or stored in a cellar and forgotten. But they can tell us much about how a book was put together – about editing, style, intended audience, economic decisions, and the structure and presentation of the text. In the Plantin-Moretus Museum in Antwerp, the proofreading room of the

Officina Plantiniana

still survives intact: displayed there are examples of galley proofs dating from the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, marked up with corrections and alterations. In the same building, the type foundry and composing rooms have type specimens on show. Framed in the early bookshop is an index of forbidden books printed by Christophe Plantin in 1569 by order of the Duke of Alba, and intended to be displayed in the bookshops of the Low Countries; it is the only surviving example of its kind.

Figure 32.3

Bill from Joseph White, bookseller, printer, and stationer, 1830. Author’s collection.

In the twentieth century, with the emergence of the professional designer and camera-ready artwork, illustration and cover design became a crucial stage in the making of a book. Even for the work of well-known illustrators and artists, much of the ephemeral evidence has been neglected and lost. Design decisions, demonstrated through these artifacts, could have a major effect on the nature and success of a book.

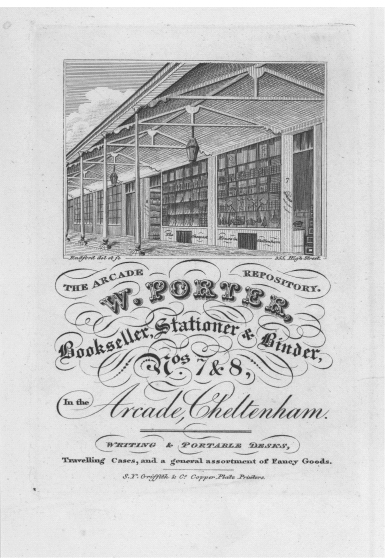

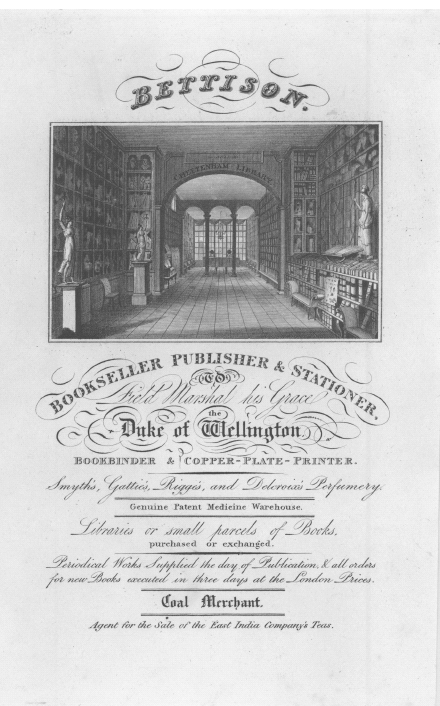

Booksellers and libraries produced trade cards, posters, and book lists that help us understand the distribution, popularity, and availability of particular titles and authors. Often such documents contain important details. A flyer for George Lovejoy’s subscription library in Reading, England of 1860 proclaims: “G. L. would just observe, that by the New Postal Regulation books can now be sent to all parts of the kingdom at a cost of 6d, and thus the contents of his extensive Library may become accessible to Subscribers in any part of Her Majesty’s dominions” (Local History Collection, Central Library, Reading, England). Illustrated advertising material sometimes depicts library façades and bookshop windows (

figure 32.4

) or detailed interiors (

figure 32.5

), giving us a glimpse of their layout and atmosphere, and often showing the array of other goods that bookshops sold. Thus, we can understand the context within which the book purchaser or borrower browsed and read. For those in rural locations, away from bookshops, the book-hawker was an essential supplier, and much of the history of hawkers can be traced through their tracts, pamphlets, and circulars.

Figure 32.4

Trade card for W. Porter, bookseller, stationer, and binder, c.1830s. John Lewis Collection, Reading University Library.

Figure 32.5

Trade card for Bettison, bookseller, publisher, and stationer, c.1830. Maurice Rickards Collection, Centre for Ephemera Studies, Reading University.

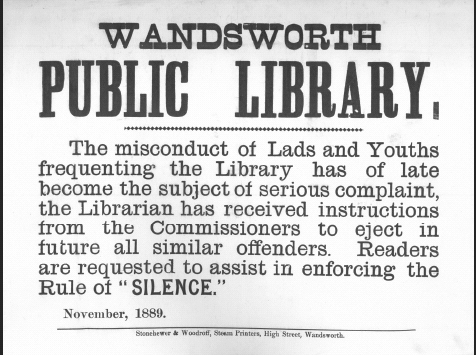

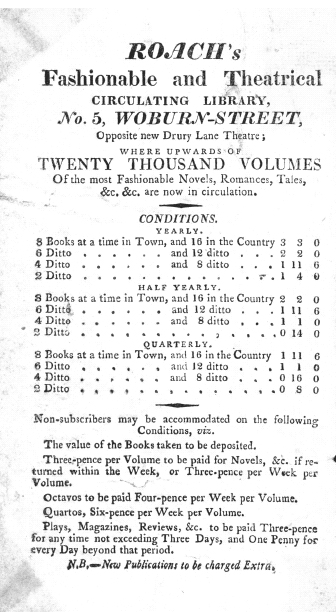

Private book owning and borrowing by individuals (

figure 32.6

) were not the only ways in which books were used and appreciated by the public. In Britain, the move toward self-education for the skilled members of the working class led to the proliferation of mechanics’ institutes (from the 1820s) and literary societies. Public libraries were set up (

figure 32.7

) and lecture programs and public readings arranged. Posters and flyers that document their activities were circulated to promote these events. Penny Readings, aptly named, became a popular source of entertainment and education in town and country. Recitations and readings from the works of Shakespeare, Dickens, Scott, and other contemporary authors – serious, comic, sentimental, dramatic – were held in public halls for the modest admission of one penny. Such societies and public readings became a common feature of American life as well.

Another kind of ephemera that can throw light on the history of the book includes items found in or pasted in books themselves. Book plates are an obvious source of information about readership and ownership (

figure 32.8

). Booksellers’ and bookbinders’ labels, reflecting the period when gentlemen had their books hand-bound for their libraries, are often found pasted onto the inside of covers. They were miniature trade cards, often printed in black ink on thin tinted paper or in gold on a flat color. The donation of a book to a library is frequently acknowledged on a printed label, as in a volume in Aberdeen University Library: “The Gift of J. Bill (His Majesties Printer) to the New College of Aberdene. 1624.” In the nineteenth century, magnificent, brightly colored, chromolithographed certificates adorned the inside pages of prize books, in recognition of high achievement and attendance at school.

The early Puritan colonists in America brought with them primers, horn books, and Bibles from the homeland. Setting up schools in the New World, they consulted manuals for schoolmasters, many of which gave good advice about the use of Rewards of Merit to promote morality and diligence amongst young pupils. Over the centuries, these precious decorative and colorful awards have been proudly carried home to parents by generations of schoolchildren (

figure 32.9

). The words and images used on Rewards of Merit are significant illustrations of the attitudes toward religion, education, achievement, and moral values that shaped American society.

Found in books but not usually attached to them is another item of ephemera – the bookmark. Known in the Middle Ages as a register, it began to be called a “marker” in the early nineteenth century. Variously made of strips of vellum, ribbon, paper, or cardboard, often decorated or embroidered by hand, the bookmarker of printed card became widespread from about the 1860s. As well as being useful for keeping one’s place, they were often rich adornments that could reflect a certain cultural status. Markers illustrated with religious themes became popular, but by the end of the 1870s the printed bookmark had largely become a marketing tool for advertisers, given away free. Sometimes a marker was made to have an additional use, such as a calendar, ruler, timetable, or puzzle.

Figure 32.6

Price list for Roach’s Circulating Library, c.1830. Maurice Rickards Collection, Centre for Ephemera Studies, Reading University.

A popular form of bookmark was made from silk ribbon, which was produced using the Jacquard weaving loom. The ribbons were elaborately woven by machine with intricate pictures, the loom being “programmed” to a preset pattern (anticipating certain elements of the computer). The best-known firm manufacturing these markers was Thomas Stevens of Coventry in England. They later became a speciality of the textile mills of Paterson, New Jersey, which was known as “Silk City, USA” in the 1880s.

Figure 32.7

Notice from the Wandsworth Public Library, 1889- Maurice Rickards Collection, Centre for Ephemera Studies, Reading University.