A Company of Heroes Book Four: The Scientist (17 page)

Read A Company of Heroes Book Four: The Scientist Online

Authors: Ron Miller

“We heard about your change

ever

so long ago,” said another.

“

Ever

so long!” emphasized either a third mermaid or the first one, not that it made any difference.

How long,

Bronwyn wondered

, is ‘ever so long’ to someone who is immortal?

She recalled how the passage of time had been fearfully distorted during her sojourn with the faeries and, with a shiver, realized that, for all she knew, years or even decades might have passed since she had dropped into the ocean. Yet that hardly seemed credible; now that she thought of it, she had not even gotten hungry yet, at least not until this moment, when these first thoughts about food made her stomach give a playful little frisk of anticipation. And the little moon, she realized, looked scarcely different last night, imbedded like a phosphorescent spider in a cobweb of meteors, than it had when she and the professor had visited it. If much time had passed, and if Wittenoom were correct, surely there would have been noticeable differences in size and appearance. Wringing as much comfort from these reasonable deductions as she could, she returned her attention to her companion mermaids.

“I don’t suppose that there’s anything to eat around here, is there?”

“Eat?”

“Yes, I’m getting hungry and I don’t know when the last time was that I ate.”

“

Eat?

Well, I

suppose

so. Why not?”

“Is there something the matter with that?”

“Oh

no!

Of

course

not. It’s just that it’s something that doesn’t come up very often.”

“Don’t you eat, then?”

“Well,

certainly,

sometimes, for the fun of it. But, you see, being immortal there’s not actually any

need

for food or eating or any of

that

sort of thing. I mean, we’re

immortal

regardless; it’s actually pretty convenient.

Musrum!

I’d have to worry all the time about getting fat!”

“I must not be a full-fledged immortal, since I’m definitely getting hungry.”

“Of

course

you’re not a full-fledged immortal . . . ”

“You couldn’t be full-fledged anyway,” put in a mermaid who hadn’t before spoken, “since of course only

birds

can be fledged.”

“ . . . although there is, of

course

, no need to be

embarrassed

about this since this happens to mortals every now and then; that is, mortals in whom the Tritons have taken an interest. It is, in fact, a

considerable

honor . . . ”

“Get to the

point

, for heaven’s sake!” hissed one of the speaker’s companions.

“ . . .

Well

, as I was

about

to say, we’re

quite

used to mortal or even semi or demimortal peculiarities. Will this help?” The mermaid slapped the surface of the water with the flat of her flukes, making a sharp, shotgun--like report that was so unexpected that it made Bronwyn start. Simultaneously with the mermaid’s action a school (or flock) of flying fish shot from the waves like a covey of frightened quail. Each mermaid plucked a fish from the air as neatly as a professional baseball outfielder snatching an easy fly ball.

“

Here

you go,” the nearest mermaid said, offering her wriggling catch to the princess, who accepted the gift a little uneasily, wondering what she was now expected to do with it. She glanced at the others, but got little help other than expectant and eager expressions. With considerable relish the mermaids sucked the flesh from the bones of their fish like a child would suck a popsicle from its stick.

Great heavens above! They’re expecting me to eat this fish right now!

She looked at the still-struggling fish, half hoping to detect in an eye that was, in actual fact, as devoid of expression as a spoonful of eggwhite, an imploring that would allow her to conscientiously return the poor animal to its home. But the creature only flopped mechanically, its gills pumping like a pair of bellows.

“Thanks very much,” she said, “but I think that I’ll save this for a snack later since, now that I think about it, I’m not as hungry as I thought.” With which words she deposited the fish into a basin of tidal water by her side, where it immediately and ungratefully began swimming in circles as though nothing had happened.

“That’s an

excellent

idea,” agreed the mermaid who had initiated the roundup, also tossing her fish into the little pool, as did the others. This proved to be so novel and fun that they caught another round of fish and tossed these, too, into the pool. They did this until the water had been entirely replaced by a pile of wriggling animals.

Bronwyn felt her tail begin to itch and when she looked at it, noticed that the scales were losing some of their luster. She swung the graceful appendage over the side of her rock to allow the waves to splash against it. The water was cool and the rehydrated scales were quickly soothed and regained their original shimmer. Brownyn admired how much they looked like tiny, bright sequins, clinquant under the golden light of the lowering sun.

Suddenly there was a kind of crackling in the air, like Musrum balling up a mile of cellophane in His fist, and at the same time a peculiar prickling came all over Bronwyn’s skin. The air became strangely tense and metallic, awakening an odd memory somewhere within the princess’s entranced brain.

“Ooh!” cried one of the mermaids, “I feel

tingly

all

over!

”

“Odd, isn’t it?” answered a companion, “Like when I caught that

dreadful

electric eel once, remember?”

That certainly sounded more than a little familiar to Bronwyn, but it was still a memory that remained tantalizingly and frustratingly aloof.

Once more the air crackled and this time Bronwyn could actually hear it buzzing, like a taut wire in a breeze. The atmosphere had become saturated with an electric fluid: she could feel the hairs on her nape and on her arms become stiffly erect, as though she had just touched the poles of a battery. She was certain that if one of the mermaids were to touch her just then, she’d receive a violent shock.

The breeze ceased entirely and a great silence prevailed in the calm that followed. The ocean heaved in lazy, oily billows.

The island that had until this moment been little more than a scarcely-noticed shadow on the horizon, capped with a towering billow of cloud, like whipped cream piled atop a sundae, drew Bronwyn’s attention. From the center of its darksome silhouette there suddenly lanced a thread of violet light that skewered the cloud like a needle passing through a skein of yarn. It looked like the dazzling thread of white-hot metal inside the globe of an electric light. The cloud flickered and pulsated with an internal commotion, like fireflies behind ground glass. From its highest billow, the princess could still see the almost invisibly fine thread as it vanished into the indigo zenith. And there in the zenith, too, was the tragic little moon, the thread of light aimed toward it like the trail of a rocket. As if it were the rocket’s target.

And as though that strange beam of light had hit her directly between the eyes, filling her head with sparkling, throbbing illumination, she was inspired and turned to the mermaids and asked, “What is that island over there?”

But as she spoke, the cloud was torn in two like a curtain and the mysterious electricity burst from it as though from a shattered galvanic cell. Fearful claps of thunder followed dazzling flashes of lightning, of an intensity Bronwyn had never experienced. The bolts crisscrossed one another and the echoing thunder pealed like a machine gun fired in a bank vault. The mass of vapor became incandescent and a shower of hailstones fell onto the islet, each detonating with a burst of light. The waves that suddenly fell upon the rocks reared up like firebreathing monsters, their crests surmounted by combs of flame.

The lightning became whimsical and took the form of fiery globes that burst like bombshells over Bronwyn’s head. The incessant lightning became an almost constant emission of light, flickering like sunlight through a rapidly rotating propeller.

Waterspouts shot up in sinuous columns, like enraged cobras, falling back to disintegrate in explosions of foam, each individual droplet fizzing and sparkling like a firework. Spikes and needles of violet and green light covered the rocks, making them look like incandescent porcupines huddling against the storm.

Brownyn did not receive an answer to her query concerning the identity of the distant island since, at the first whipcrack of thunder, the mermaids had in practiced unison dived from the islet into the safety of the serene and saline depths. But the island, Bronwyn realized, didn’t need a name since

she

knew what to call it: Tudela’s Island.

The princess eradicated the distance between the mermaid’s islet and the mysterious island like a furious torpedo; not wavering half a degree from the course, her powerful flukes propelling her like the blades of a turbine. When she saw the shadowy flanks of the island’s foundations loom darkly ahead of her, she surfaced to reconnoiter. In front of and above her were wild ramparts of broken basalt heaped into fantastic and ragged shapes. like buttresses supporting the island itself, vast arches of black stone connected sea and cliffs. Through their openings, the frustrated waves lashed and frothed. At the jagged edge of the cliffs, high above her head, Bronwyn could see a dozen wan-looking trees, resembling twisted bits of wire more than anything alive. The cliffs looked stark and lifeless until she caught a glimpse of something moving among the great piles of broken rock at their base. Though it looked like little more than a scrap of windblown cloth, it was a human figure. She dived back beneath the grey, beating surf and with a few powerful strokes reemerged near where she had seen the human. As her head rose above the surge, she was at first almost deafened by the thundering roll of the breakers as they beat themselves uselessly against the adamant basalt. Somewhere amidst the sound she seemed to hear her own name,

bronbronbronwynbronwynwynwyn.

Was she so close to land that the sea itself was pleading for her return? She cleared her face of the strands of kelpy hair that clung to it and as her vision cleared she saw that her name was not mysteriously being called by the waves, but, more prosaically, by the tall, lanky figure that clung precariously to the slippery boulders just above her head.

“Bronwyn!” it called again.

“Professor Wittenoom!” cried Bronwyn, “Whatever are you doing there?”

“Clinging for dear life. But better I should ask, I think: whatever are

you

doing

there?

”

“Treading water.”

“It’s very good to see you! Do you know, I thought that you were dead? Drowned?”

“I thought so myself, at first. And it’s good to see you, too, Professor.”

“An odd time and place to go skinny-dipping, if I might say so.”

“I can’t help it, I’m a mermaid.”

“Literally or figuratively?”

“Literally. Some god or another turned me into one, to save me from drowning.”

“Decent of him or her. But I wouldn’t have thought it possible, anatomically speaking. Icthyology, however, is not my field, let alone comparative anatomy, so I can’t speak with any sort of expertise, you understand.”

“Of course. Here, look at this,” she offered, doing a neat somersault that finished with a showy flick of her tail.

“Remarkable.”

“How did you get onto the island? I take it that’s where your parachute took you?”

“You are correct, but after what I’ve found here, it almost seems inevitable that I land here.”

“What do you mean?”

“The secret of the moon, it’s here on this island.”

“I knew it!” cried Bronwyn. “It’s Tudela’s island, isn’t it?”

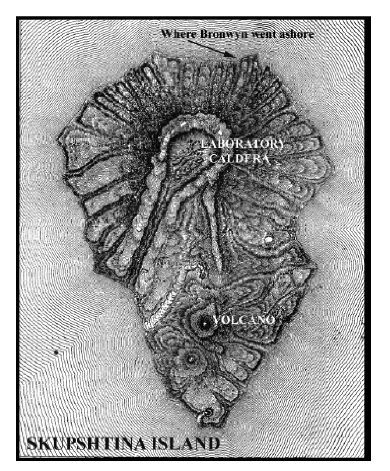

“I don’t think so. I looked on a map and it’s called Skupshtina.”

”No! No! That’s not what I mean. Tudela’s

here

, isn’t he? On this island? Dr. Tudela?”

“Oh! Yes, of course he is. How could you possibly have known that?”

“Uncanny, isn’t it?”

“Look here, Princess, it’s getting awfully cold and wet. Why don’t you come and join me someplace dry and warm? Then we can catch up with what’s been going on?”

“I can’t!”

“But . . . Oh. I see. Sorry. That was silly of me. But, tell me, what are you going to do about, ah, your condition? You can’t remain demipiscine forever, can you?”

“I don’t know, I hadn’t much thought about it.”

“What are those things on your neck?”

“Oh. Those are my gills. I only need them when I’m swimming underwater.”

“Well . . . look here, Princess, there’s an awful lot about which I think you ought to know, about what’s been occuring on this island, but I don’t know what you’re going to be able to do about it . . . ”

“I can see what you mean. If you must know, I didn’t ask to be this way, though the thought was certainly well-intentioned: I would certainly have drowned otherwise. But I don’t know that I enjoy it all that much. If you must know, the conversation’s less than compelling. I’m not sure what, exactly, I can do about it, however.”

“You

must

do something. I need your help to stop Tudela’s madness. I’m the only one here besides him and his associates. He only allows me my freedom because he considers me harmless and the island escape-proof. Although electrical phenomena are outside my field, I understand enough to know what he’s doing and have some idea of how his devices operate. Running the Academy for so many years has taught me a smattering of just about every discipline, you see. He thinks that you’re dead, by the way, especially since I seemed convinced of your demise, in spite of my hopes. With your presence on the island unknown to him, I think that we could put paid to his evil schemes.”