A Complicated Marriage (14 page)

Read A Complicated Marriage Online

Authors: Janice Van Horne

But for Lee, the waiting and watching were over. She came home a little more than twenty-four hours after the phone call. All business, she immediately took control and swung into action: the body, autopsy, funeral arrangements, gravesite, newspapers, the will, who would put up the imminently arriving family membersâall the subtexts of death. Lee dispatched them with dazzling proficiency and speed. She knew exactly what she wanted and got it. With one exception: the eulogy.

Clem saw her briefly the day she got home, and she mentioned the eulogy. She took for granted that Clem would give it. No discussion. She said only that she would call the following morning to go over the details. She then moved on to the next pressing item on her agenda. That evening, Clem started to compose his thoughts. The clearer they became, the more disturbed he was. He knew what he had to do. When Lee called the next day, he said that yes, he would speak about Jackson. Then he added that she should know up front that he would be mentioning Edith Metzger's death. She must have objected quickly and loudly, because the next thing I heard Clem say was that it was the right thing, the ethical thing, to do. And then again, after Lee's response, he repeated with finality that, ethically, he could not speak about Jackson's life without referring to Edith's death. Over her escalating protests, he suggested other speakers: Barney Newman and Tony Smith. Lee, being Lee, told him that there would be no eulogy and hung up abruptly.

So much for Edith Metzger's moment in the sun

, I thought but didn't say. I didn't think Clem would appreciate my black humor that morning.

So much for Edith Metzger's moment in the sun

, I thought but didn't say. I didn't think Clem would appreciate my black humor that morning.

The funeral was held on Wednesday afternoon. It was a beautiful day, and we went to the beach for a few hours. When we got to the small church, it was jammed to overflowing. It must have been 120 degrees. I had never been to a funeral and I was shaken by the sight of the coffin, stark and alone up front. I had already buried Jackson, and now there he was. The tears came. No sobs, nothing dramatic, just a steady flow down

my face. The ceremony was short: prayers, some music, and a minister who drily summarized the highlights of Jackson's life. We then went to a nearby cemetery where, the day before, Lee had bought plots for Jackson and herself. A few more rote words, Lee dry-eyed, stoic. There would be no drama or catharsis that day. It seemed like only minutes before we were back in the car, headed for a gathering at the house. Such a rubber-stamp finale for a marriage, for such a passionate, unpredictable spirit, and for the best painter America had ever produced, or so Clem had written over the years.

my face. The ceremony was short: prayers, some music, and a minister who drily summarized the highlights of Jackson's life. We then went to a nearby cemetery where, the day before, Lee had bought plots for Jackson and herself. A few more rote words, Lee dry-eyed, stoic. There would be no drama or catharsis that day. It seemed like only minutes before we were back in the car, headed for a gathering at the house. Such a rubber-stamp finale for a marriage, for such a passionate, unpredictable spirit, and for the best painter America had ever produced, or so Clem had written over the years.

After a subdued start, the party was soon in full swing. Everybody said there had never been such a wonderful party there. There was an abundance of food and drink. People spilled out into the yard. I heard grumblings about the lackluster funeral, the minister who knew nothing about Jackson, who had never even met him, how somebody should have said something, how it didn't seem right. Of course, I had thought the same things, but now I wondered if anything would have satisfied people's needs, and thought it had probably been best the way it was. The myth machine had already started rumbling. “The great painter who lived in violence died in violence” sort of garbage. As for the people at the house, I think we were still in shock. The word

inevitable

kept coming up, but I had learned that week that inevitability doesn't lessen the shock of death.

inevitable

kept coming up, but I had learned that week that inevitability doesn't lessen the shock of death.

Sure, I knew that drunks were drawn to cars and to speeding. My mother always hid the car keys from my stepfather at the first sign of a binge. Thwarted, Harry would run down the street, sometimes naked. He wanted out, out of the house, out of his skin, just out. If he did find the keysâdrunks are cannyâhe would speed off and my mother would call the cops. One time, when maybe he didn't have any yen for speed left in him, he closed the garage doors and turned on the ignition. The garage was under my bedroom and I heard the motor running. Foiled again. Until the next time.

Jackson's large family had come for the funeral. Throughout the party, his mother, Stella, sat on an upright chair in front of the TV. I approached her to offer my condolences. She nodded. I asked if I could get her anything to eat. She said she was fine. Her eyes barely strayed from the

Democratic convention, a shoo-in for Eisenhower's second term. Yet how engrossed she was. She was stolid, like a stop sign. I brought a plate of food and set it down near her, just in case.

Democratic convention, a shoo-in for Eisenhower's second term. Yet how engrossed she was. She was stolid, like a stop sign. I brought a plate of food and set it down near her, just in case.

A more lively attraction at the party was Sande's five-year-old, Jay. Adorable and outgoing, he and I tossed a ball around. Later, when Sande asked if I would take Jay to the beach the next day, I was thrilled, if a bit aflutter, having never been around a child before. The family stayed for three more days, and each morning I picked Jay up and off we went to the Coast Guard and our world of sand castles. I loved our times together and loved driving through town with the top down and him next to me. I hoped people would think I was his mother. It was probably good they left when they did; my fantasies were running amok.

In the days and weeks that followed, Clem's focus was on Lee. Her pace had slowed. She now made a mountain out of every decision. She talked endlessly to everyone in her circle about the ins and outs, the pros and cons, all the while knowing full well what her course of action would be. Her emotional state was something else. As fiercely strong and pragmatic as she appeared to be, she was also fiercely needy, especially at night, when her to-do list wasn't an option. Unfortunately for me, Clem was her number one confidant. Her tantrum over the eulogy had flared and quickly fizzled, as her need for Clem superseded her grudge. He was at her house sometimes twice during the day and then again in the evening. Several times he spent the night there. Feeling very woe-is-me, I pouted and sulked. To no avail. The new bride didn't stand a chance against the grieving widow.

Clem was stretched thin. He, who prided himself on never getting sick and never having had a doctor, caught cold. And then one night he got up to go to the bathroom and I heard a thud. I ran in and there he was, out cold. My first thought was that my stepmother, Marge, had been right; Clem would die long before me. But not this soon! A few splashes of water and a lot of yelling brought him around. He got up and returned to bed.

I was frantic. “What happened?!”

A shrug. “Must be my thyroid is low.”

Clem had a theoryâon those rare occasions when his body felt a

bit “off,” he blamed his thyroid and would down one of my thyroid boosters. Of course, being his own best, and only, doctor, he had never been diagnosed. He then turned over and went to sleep. I lay there like a zombie, my brain clattering for hours as it spiraled through sudden-death scenarios and funerals, the freshly minted bride turned widow weeping into the grave.

bit “off,” he blamed his thyroid and would down one of my thyroid boosters. Of course, being his own best, and only, doctor, he had never been diagnosed. He then turned over and went to sleep. I lay there like a zombie, my brain clattering for hours as it spiraled through sudden-death scenarios and funerals, the freshly minted bride turned widow weeping into the grave.

Not helping my frame of mind during those last weeks in August was Friedel's latest obsession. Since the night of Jackson's death, he believed Jackson's spirit had taken up residence in him. He

was

Jackson. Given Friedel's unstable physical and emotional state, Clem had tried to dissuade him from going to the funeral. But of course Friedel had insisted. He had managed the church without incident, but at the cemetery, with the ghoulish Marisol at his side, he had stood so close to the edge of the grave, sobbing, staring down at the coffin, that I was sure he was going to jump in. What a pair. He took to hanging around the cemetery and several times drove down to visit Ruth at the scene of his recent tortures, the South Hampton Hospital. Naturally, whether he was inhabited by God, Matisse, or Jackson, the scraggly beard remained.

was

Jackson. Given Friedel's unstable physical and emotional state, Clem had tried to dissuade him from going to the funeral. But of course Friedel had insisted. He had managed the church without incident, but at the cemetery, with the ghoulish Marisol at his side, he had stood so close to the edge of the grave, sobbing, staring down at the coffin, that I was sure he was going to jump in. What a pair. He took to hanging around the cemetery and several times drove down to visit Ruth at the scene of his recent tortures, the South Hampton Hospital. Naturally, whether he was inhabited by God, Matisse, or Jackson, the scraggly beard remained.

Within a week or so, life in East Hampton flattened to a hum. As if the tidal wave that had engulfed us all had subsided and would not strike the town again. At least that summer. The out-of-towners returned to where they had come from. Parties were held, beach life continued, late nights of drinking and dancing at the dives, all that. But with a subdued air. Also in the air was the smell of Labor Day, and with it my release from the blissful summer I had imagined, the summer that had gone so terribly wrong. Self-protection led me to endow East Hampton with all the troubles that had eddied around us. That way, I could believe that, as we packed up and headed back to New York, the bad times wouldn't be following us home.

Â

A single mom with the kids, Green Haven, 1941.

Â

With my father, Green Haven, 1938.

Â

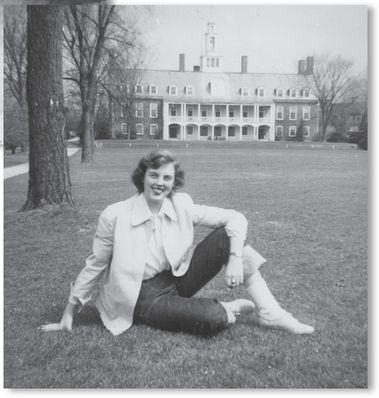

A Bennington sophomore, 1952.

Â

Jackson Pollock memorial show at MoMA, 1956.

Â

Our first photo, 1955.

Â

The Kunsthistoriches, Vienna, 1959.

Other books

The Midwife of Hope River by Patricia Harman

Listen Here by Sandra L. Ballard

The Women of Brewster Place by Gloria Naylor

Dessert by Lily Harlem

Xantoverse Shadowkill by T. F. Grant, C. F. Barnes

Drinks Before Dinner by E. L. Doctorow

Secrets on Saturday by Ann Purser

JeBouffe Home Canning Step by Step Guide (second edition) Revised and Expanded by Tremblay, Edith, Lafleur, Francois

The Other Side of the Story by Marian Keyes

Metal Fatigue by Sean Williams