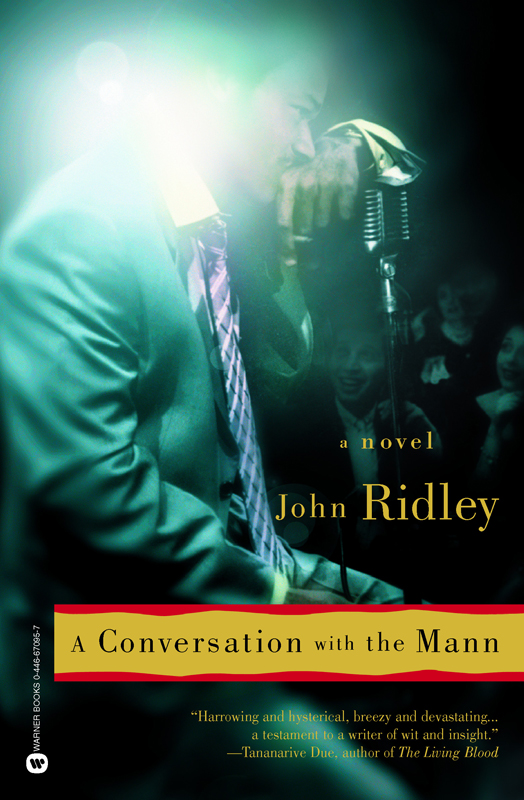

A Conversation with the Mann

Read A Conversation with the Mann Online

Authors: John Ridley

This book is a work of fiction. Names, characters, places, and incidents are the product of the author's imagination or are

used fictitiously. Any resemblance to actual events, locales, or persons, living or dead, is coincidental.

Copyright © 2002 by John Ridley

All rights reserved.

Warner Books, Inc.,

Hachette Book Group, 237 Park Avenue, New York, NY 10017

Visit our website at

www.HachetteBookGroup.com

.

Originally published in hardcover by Warner Books, Inc.

First eBook Edition: June 2009

ISBN: 978-0-446-56295-9

Contents

August of 1957 to February of 1958

June of 1959 to January of 1960

February of 1960 to December of 1961

January of 1962 to June of 1963

ALSO AVAILABLE FROM WARNER BOOKS

Everybody Smokes in Hell

Love Is a Racket

Stray Dogs

I

II

III

IV JER V

T

he Green Kitchen was where I first met Jackie Mann. The Green Kitchen was on Manhattan's Upper East Side. The Green Kitchen

was a little restaurant/diner kind of place where me and the boys—Sweeny, Richie, Raider, God bless him—used to chow down

after doing sets at The Strip, Catch, and Stand Up, among very few other comedy clubs we were limited to working. That is,

if you call hanging out till two A.M. hoping to go on for the six people left in the audience working. But that's what we

did, hang out, because the two A.M. slot was when all the hotshot club bookers—who used to be bartenders before the comedy

boom in the eighties turned their saloons into comedy spots and made them hotshot club bookers— would swing young comics like

us. Of course, the eighties ended, and so did the comedy boom, and most of the clubs closed and the hotshot club bookers went

back to being bartenders. But that's not the story I'm trying to tell.

I'm trying to tell the story of how I met Jackie Mann at the Green Kitchen, where us wannabe comics used to chow down. It

was a good hangout. After a hard night of fifteen minutes of joke telling, there was much griping to be done and many road

stories to be swapped. One morning, post-griping and swapping, when the boys were ready to head home, I took our collected

money to the counter to pay the bill. Standing there was an old black guy who mumbled at me: “Gimme a dollar. I don't have

enough to pay for my fries,” or something close to that. The man didn't look shabby or indigent. He just looked like a guy

who'd left home a little short and was asking to get covered for a buck. But he'd said what he said sharp and matter-of-fact.

He said it like I owed him a dollar. He said it in a way that made me think the entire world owed him a little something.

I gave him two dollars.

I got no thank-you from him. He said, instead, that he had seen me around a few times and wondered what I was doing at the

Green Kitchen so late at night, and I told him I was a comedian and he laughed a little and said “Yeah?” and I said “Yeah”

and he said “You know, I used to be a comic.”

I didn't know that, not even knowing who this old black guy was.

He told me his name was Jackie Mann and I told him—young and cocky like I used to be—my name, and that he should remember

my name because one day my name was going to be real well known. One day I was going to be very famous.

Jackie laughed again.

At

me. And then he told me that I shouldn't get any ideas about being a star, because that's all they would most likely ever

be.

This time I did the laughing. Who was this guy to tell me I wasn't going to be famous? All of us, me and the boys—Sweeny and

Richie and Raider, God bless him—were going to be big.

Didn't much work out that way. Sweeny went on to write gags for talk shows, Richie kept plugging away in the club scene in

New York. Raider … God bless him. But that's not the story I'm trying to tell.

I'm trying to tell the story of how, after I met Jackie Mann, I couldn't quite get him out of my head. I don't know why. I

had never heard of him, and that right there should've made him very forgettable. I was a comic and I knew comics and I don't

just mean the big guys with the sitcoms or the bigger guys with the movie deals. Pigmeat Markham, Olsen and Johnson, Ernie

Kovacs, Godfrey Cambridge, George Kirby. Famous or not, black or white, I knew my history, and if I didn't know anything about

Jackie Mann, then Jackie Mann wasn't worth the energy it took to speak his name.

Still …

The way he laughed at me, said to forget about having big dreams, it made me think he knew what he was talking about.

There was a comedienne who hung out with me and the boys whose father used to work in television back in the golden age. I

asked her to ask her dad if he had ever heard of Jackie Mann.

She asked him.

Boy, had he heard of Jackie Mann. He remembered, pretty clearly, the stories that I would come to know real well: Jackie's

days doing shows at the Copa and Ciro's, mixing company with the likes of Sinatra, Dino, and Damone. His on again, off again,

up/down relationship with his girl Tammi, the surprise wedding, the thing with the Fran Clark show. And, of course, the Sullivan

show.

I feel embarrassed now, listing events and incidents that, remembered and familiar to many, were once unknown to me. I feel

ashamed that a guy like me, a guy who thought he knew a thing or two about the history of both comedy and his people, was

so completely ignorant.

I chose to be ignorant no more.

I went back to the Green Kitchen a few times before happening across Jackie again, and asked him—begged him—to share his memories

with me.

Thankfully, he did.

And over many plates of french fries Jackie told me tales of a long-gone era with a verve and lingo that made every moment

fresh and vivid. Putting Jackie's story on record—a story of time and place and history—has taken well more than a decade.

It waited as I went from New York to Los Angeles, from stand-up to television and screenwriting to finally—thankfully—publishing.

Fortunately, like a fine wine, Jackie's is a story that has only gotten better with age.

And that is the story I'm trying to tell.

John Ridley

March 28, 2002

Hollywood, California

L

et me tell you:

You stop. You can't go on. Can't say another word. The clapping roadblocks you; the sound of the flesh of a thousand hands

beating against each other. Men's hands—manicured, most likely, and pinky-ring-decorated. Women's hands—most likely jeweled

on five or six or seven out of ten fingers; rings that match bracelets that match necklaces that match earrings. Most likely.

You don't know. Not for sure. To all that you're blinded: the gems, the bouffants and pompadours, the sharkskin suits and

the satin dresses; you're blinded to the high style of the times. The arc light spotting you cuts your vision and knocks down

the people and all their finery to a silhouetted mass—a living ink blot—that jukes and jives and howls as a single thing.

Let me tell you:

It's better that way. Better they should be unreal and unintimidating, and that you are ultrareal, illuminated. Glowing. Three

feet taller on the stage where you stand over the tables where they sit. Sight gone, all you're left with is the taste—yeah,

the taste—and smell of the people; the smoke belched train-style from Fatimas and Chesterfields, chewably thick and unavoidably

swallowed, but overpowered by twenty varieties of perfumes that run the scale of stink from Chanel to Woolworth's. You're

left with the sound of the thousand hands and the whistles and the roaring voices with the occasional call that comes after

a joke: “That's true. That's funny 'cause it's true.” And all that keeps you from saying another word. You can't go on.

So, let me tell you:

I didn't go on. I stopped and I stood and waited for that ink blot to finish cracking up. I stood and I waited and I soaked

up its applause and affection. I waited, and the waiting took time. The time the waiting took made the second show in the

Copa Room at the Sands hotel and casino in Las Vegas, Nevada, run long. Like an unbreakable law of nature, the second rule

of casinos was that the entertainment shows never ran long. The first rule was that you let the customer drink for free. Drink

for free, eat for free, lodge for free … Generally you kept 'em happy so that you could keep 'em at the tables, where the

odds are so stacked against them it's nothing but easy to separate money from their well-liquored, well-fed fingers. But for

the casino to get their dough the customer had to be at the tables, and they couldn't be at the tables when they were in the

show room laughing it up, swinging to some crooner, or otherwise engaged in non-gambling. The management, the boys from New

York and Chicago and Miami—a balancing act of strong-armed Italians and slick-minded Jews—who quietly, very quietly, ran the

casinos, didn't much care for their customers to be non-gambling. They hadn't traveled from city to desert to open a chain

of hospitality suites. So rule number two: The entertainment shows never ran long. Hardly ever. The first day of October 1959

was an exception; twenty-four hours that were particular otherwise only in their insignificance: The Russians were behaving

themselves. The Donna Reed show was new to TV. It'd only been a bunch of months since Barbie's first date with America. Freshly

fifty-stated America. Other than that it was just another Ike-is-president Castro-is-evil Elvis-is-God day. Except, the second

show in the Copa Room at the Sands hotel and casino in Las Vegas, Nevada, did the unthinkable and ran long, and it ran long

because of me, and I wasn't worried in the least about upsetting the Italians or the Jews. I was the opening act for Mr. Danny

Thomas. The opener of any show got exactly six and a half minutes to warm up the audience for exactly forty-three and a half

minutes of headline, straight-from-Hollywood, star-powered entertainment before they were herded back out to the casino for

another complimentary mugging. But on that night, same as a lot of nights, I'd killed. I hadn't just done well; I'd slain

the crowd, left that ink blot flopping in the aisles. I had to stand and wait for the people to drain themselves of laughs

and claps.

Some headliners don't dig an opener going over big. You get rolling and they'll have you yanked two and a third into your

six and a half. The show is about them and only them, and don't even try to give them something to follow. But Danny Thomas

wasn't Charlie Small-time. Danny Thomas was the spit-taking star of the number four Nielsen-rated show on television. Danny

Thomas could follow whatever I put out and take it higher. He tossed me the signal to stretch, to do an extra couple of minutes.

An extra couple of minutes that would make the long show run even longer. So what? The management wasn't so Guido they didn't

know an audience

that

good-time high translated into a bunch of crazy bets once they got back to the tables.

So let me do some extra bits.

Keep that customer happy.

I finally wrapped and Danny hit the stage, bringing me back out for a few bows. As he launched into a trademarked “Danny Boy”—

the backing band big and brassy—and rode the crowd into his own special groove, I took up a spot at the back of the room,

got perspective, and started questioning myself: How did I get here? A black kid from Harlem working the finest club in the

glitziest city in the world, opening up for one of the biggest acts in entertainment. After only a handful of years of really

making a break in show business, and there was almost nothing I didn't have. There was almost nothing I couldn't do.

Nothing, except walk out the doors of the Copa Room and into the casino itself.

It was 1959, and the only difference between Las Vegas, Nevada, and Birmingham, Alabama, was that down South they posted signs

telling a black man where he couldn't go and what he couldn't do: WHITES ONLY, COLOREDS NOT ALLOWED. In Vegas you had to figure

that out on your own. You figured it out quick-style. Stay off the Strip, stay in Westside. Stay the hell away from

their

casinos. Didn't matter how well you did in the show room, didn't matter how much the audience laughed or clapped or how many

bows you took,

out there

it was still 1959, and

out there

blacks weren't welcome. Not to stay overnight. Not to eat. Not to gamble.