A History of China (34 page)

Read A History of China Online

Authors: Morris Rossabi

Chan was still another sect that flourished during the Tang. This teaching slighted the use of the intellect to achieve enlightenment. Instead it proposed meditation as a means of attaining enlightenment, which was identified as the Buddha-nature that each individual possessed within himself or herself. Human logic would not lead to enlightenment, a state that culminated in a perception of the unity of all phenomena. This state could not be described in words. It could be perceived only in feelings, and an outside observer could not gauge whether an individual had achieved the spiritual awakening of enlightenment. Study of the Buddhist writings and proper conduct according to Buddhist precepts were irrelevant and could detract from the intuitive response essential for enlightenment. One school within Chan believed that such intuition and the ensuing breakdown of reason necessitated jarring and occasionally devastating “attacks” to undermine the logical defenses that impeded the effort to arrive at a Buddhist nature of spontaneous, intuitive responses. A Chan master might yell at or beat an acolyte, or insist that he stay awake for long periods – all deliberate attempts to undermine the rational faculties. The master might also pose problems (

gongan

) to assist the disciple in moving beyond human logic. These problems were often paradoxical and were designed to elicit intuitive, nonrational answers. Such questions as “can you hear one hand clapping?” defied reason and required an intuitive leap. A verbal response to these queries was not necessarily a good choice because Chan mistrusted words. A smile, a frown, or other facial or body signals were more effective means of communication.

Chan, with its individualism and spontaneity, appears to clash with Buddhist views and to have more in common with Daoism. Its disdain for Buddhist texts, worship, and rituals meant it diverged considerably from other sects, but its defenders declared that their objective – achieving enlightenment – was precisely what Buddhists valued. Moreover, they did not distance themselves from Daoism because they did not repudiate attitudes of naturalness and spontaneity, scorn for verbal communication, or the possibility of Buddhahood and

dao

within the individual; they shared all these beliefs with Daoist masters.

Numerous stories and myths have developed about the Chan leaders who introduced the sect in China. Bodhidharma, in particular, a patriarch of the sect in the fifth or sixth century, was the central figure in a number of accounts concerning the development of Chan in China. He arrived from central Asia and began to teach that enlightenment lay within the individual and that nonverbal means were the ideal vehicles for transmission and understanding of Buddhism. He and his fellow Chan proponents, however, by the nature of their teachings – which relied on a one-on-one master–disciple relationship – did not attract a wide following.

The Pure Land school became the most popular sect of Buddhism. It did not require a disciplined or ascetic life, deprived of sensual pleasures, nor did it demand extensive study or meditation. It emphasized salvation, not rigorous activities leading to enlightenment or self-knowledge. In other words, it was easy to practice, and its objective was appealing. The two versions of the

Pure Land Sutra

embodied its principal teachings; one version simply focused on sincere faith as the road to salvation while the other stressed that, in addition to faith, good works were essential. The version of the

Sutra

that attracted the largest number of adherents was the one that stressed faith alone. According to the text, the final objective was rebirth in the Pure Land, a Western Paradise presided over by Amitabha. This idyllic land, described as a virtually perfect environment with beautiful flowers and trees next to rivers redolent of sweet fragrance, was accessible if the worshipper believed in Amitabha with a sincere heart. It was taught that Buddha had facilitated the individual’s rebirth into the Pure Land because of the merit he had accumulated, which he had then transmitted to the rest of mankind. The only criterion for entrance into this paradise was belief in Amitabha, as reflected in chants of devotion directed at the creator and guardian of the Western Paradise.

Guanyin assisted Amitabha in easing entry into the Pure Land. As a bodhisattva – that is, a person who had achieved Nirvana but returned to help others do so – Guanyin was a compassionate figure who protected humans from evils and threats and to whom childless women would pray to give birth to a son. Originally depicted in sculpture and painting in a male form, in later times, particularly after the Song dynasty, Guanyin appeared as a female. She was also often portrayed with numerous arms, indicating her desire and ability to embrace the world.

Pure Land’s simplicity made it appealing, and some of its proponents further simplified it. Daozhou (562–645) advocated repetition of the Buddha’s name as a means of assuring entry into the Pure Land, a proposal that reputedly led one of his disciples to utter the Buddha’s name one million times in a week. Shantao (613–681), one of his other disciples, urged chanting of the sutras and worshipping of images of the Buddha, along with repetition of the Buddha’s name, as useful recipes for entrance into the Western Paradise. As a result of its simplicity, Pure Land grew astonishingly during this era, as evidenced by the increasing number of representations of Amitabha and Guanyin in Chinese Buddhist art. They tended to supersede the depictions of the historical Buddha and of Maitreya, the Future Buddha. Also of great popular appeal were paintings of the horrors of Hell and the delights of the Western Paradise. No wonder that Pure Land was found attractive by many Chinese who did not wish to undergo the strict discipline or exercises in meditation or the reading and analysis of complicated writings required in other Buddhist sects.

While these sects gained adherents, the monasteries and nunneries flourished, and many became involved in secular activities. Under the equal-field system monks and nuns received land, and the Tang rulers also granted sizable holdings to the monasteries. By combining their allotments, some of the monasteries had substantial estates. In addition, the failures of the equal-field system led to the imposition of additional taxes on peasants, who were occasionally compelled to abandon their land or to sell it to large landlords or to monasteries. Wealthy patrons also contributed to the monasteries with donations of land, and monasteries could call upon a large number of peasants, many of whom were criminals, orphans, or farmers dispossessed of their lands, to farm their estates. Because their holdings were tax exempt, the monasteries garnered sizable profits that enabled them either to buy additional lands or invest in other enterprises. The monasteries had a variety of potentially profitable ventures, including loans with interest to merchants. They also established pawnshops, oil presses, inns, and even banks.

These secular activities generated funds for the monasteries. No wonder then that they could afford to construct beautifully landscaped temples of ample scale. Within the temples were splendid images of gold, silver, or bronze, as well as bronze bells, incense burners, and ritual vessels. The monks, in addition, did not deprive themselves, wearing elaborate silk robes and enjoying well-prepared and far-from-measly repasts. Some accumulated their own lands, animals, carts, and valuable religious articles. Quite a few did not lead a life of austerity and discipline. No wonder then that unscrupulous, ill-educated, and profit-minded individuals sought ordination as monks, compelling the Tang government to assist in expelling unfit slackers and profiteers from the monasteries. The government also devised examinations to test a prospective monk’s knowledge of Buddhism before he was accepted into the monastic fold. However, being frequently in need of income, it also occasionally sold certificates that provided immediate ordination for monks. In addition, the emperors could furnish certificates enabling laymen to be accepted into the monastic orders. The monks had their own organization and hierarchy, but the government also appointed officials to scrutinize the monasteries’ activities. As the dynasty waned, these officials were principally eunuchs who were often accused of expropriating some of the monasteries’ property for themselves.

Aside from maintenance of the monasteries and perhaps ill-advised luxuries and corruption, the income generated from the Buddhists’ property served a variety of purposes. It supported the various festivals organized by the monasteries in commemoration of state and religious rituals; the translation of Buddhist writings; schools for training acolytes; and the propagation of Buddhist teachings to the population through colorful and marvelous stories from the Buddhist sutras.

A variety of foreign religions from west Asia reached the Tang, but none had the same success as Buddhism. Persian merchants and travelers exposed China to Zoroastrianism and Manicheism, but these religions did not attract a wide following. Manicheism had a greater impact on the non-Chinese along China’s northern frontiers. Jewish merchants traded along the Silk Roads, but no Jewish community settled in China until the twelfth century, and even then the community consisted of just a few thousand residents. West Asian traders and emissaries also introduced Nestorianism, a heretical form of Christianity that was banned from Europe in the fourth and fifth centuries, to China. Nestorianism had scant influence on the Chinese; its only surviving contribution is a stele that describes the religion’s main tenets. It too found a more receptive audience among the peoples living north of China, especially the Mongols. All these west Asian religions espoused sole-truth beliefs that did not suit China’s eclectic views. A Chinese who could simultaneously be Confucian, Daoist, and Buddhist in respective parts of his life would not wish to abandon his previous beliefs and practices for a sole-truth religion.

The only other west Asian religion was Islam. Muslim merchants reached China both by the Silk Roads and by sea. Arabs and Persians navigated across the Persian Gulf to the Indian Ocean and eventually arrived in Guangzhou, Quanzhou, and other ports of southeast China. Relations between them and the Tang were generally harmonious, partly because they did not seek to proselytize the Chinese population. Other than a battle near the Talas River in central Asia in 751 between an Arab force and a Tang army, the Muslims lived peacefully in virtually self-governing communities in southeast and northwest China. The Tang offered them considerable leverage because they performed valuable services for China. The court recruited them for positions as translators and interpreters and, perhaps as important, often employed them in the empire’s horse administration. It recognized that the Arabs and Persians were more adept than the Chinese in breeding and tending horses. Muslim traders imported a variety of goods, and Chinese merchants and even officials profited from this commerce.

LORIOUS

T

ANG

A

RTS

The prosperity of the Buddhist monasteries had a positive influence on the arts. Other than the funerary figures at the tombs of emperors and nobles, most of Tang sculpture reflected Buddhist interests and patronage. The emperors and the monks themselves commissioned colossal statues – both life-size figures and miniature sculptures of Buddhas and bodhisattvas. Many of the sculptures revealed a combination of indigenous and foreign elements, with Indian sensuality combined with Chinese sensitivity to line, for example. This same mélange of the native and the foreign was integral to Buddhist painting of this era, much of which was destroyed during a devastating repression of Buddhism in the ninth century. Contemporaneous sources reveal that foreign painters worked in and were much admired by Chinese artists. A number focused on Buddhist subjects, and their techniques and themes influenced native painters. The Dunhuang caves, found along the Silk Roads, yield a treasure trove of wall paintings of events in the life of the Buddha and the bodhisattvas, with landscapes and portraits dominating.

Secular painting flourished as well, though few examples have survived. None of the portraits produced by Wu Daozi (680–740), one of the most renowned of these painters, are still extant. The excavation and opening of several tombs in the 1970s enriched knowledge of Tang painting because delicate portraits of court ladies, as well as poses of dynamic lions and other animals, adorn the walls. The tomb of Empress Wu, which is perched on a hill overlooking the tombs in the valley below, has not been excavated, but the presence there of a considerable cache of paintings, perhaps exhibiting both Buddhist and secular themes, is uncontested. Painters also depicted court scenes and landscapes, with Yan Liben (ca. 600–673) and the scholar and poet Wang Wei (699–759) leading the way respectively in the two styles.

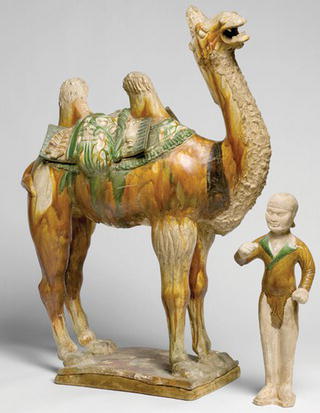

Figure 5.1

Tomb figure of a Bactrian camel, Tang dynasty. Philadelphia Museum of Art, Pennsylvania, PA, USA / Gift of Mrs. John Wintersteen / The Bridgeman Art Library

As in painting and sculpture, Tang crafts reveal considerable foreign influence. Persian motifs and shapes had a significant impact on Chinese gold and silver vessels. Sassanid Persia had achieved a high level of craftsmanship in its metalwork, and borrowings and adoptions by Chinese craftsmen manifested their recognition of the striking Persian sophistication in the production of gold and silver vessels. Tang ceramicists also made great strides and adapted the shapes and designs of Persian metalwork in their plates, ewers, and bowls. The presence in China of Persians, who probably fled from the Islamic armies, facilitated the transmission of Persian styles, and the resulting forms and décor, including the foliate pattern on bowls and dishes, the pilgrim bottle, and grapevine, all evince Persian and central Asian influence. The figures represented in the decorations were often central Asian or west Asian entertainers, merchants, or soldiers. The ceramics frequently borrowed designs from textiles and other materials. The glazes, made of cobalt, iron, or copper, were more varied than in earlier dynasties, with colors stretching from blue and green to yellow and brown, culminating in the creation of the tricolored ceramics for which the Tang is justifiably renowned. Kilns in the north used a slip (clay made semifluid with water and used for coating pottery) and produced a white, high-fired ware that resembled though was not as hard as porcelain, while kilns in the south produced green ware, occasionally with lotus and flower designs. Central Asian designs and shapes had a greater influence in the north, which also had the more elaborate burials and which thus required ceramic figurines as tomb artifacts. These figurines varied in size from big camels and horses to much smaller musicians, soldiers, and servants.