A History of the World in 100 Objects (13 page)

Read A History of the World in 100 Objects Online

Authors: Neil MacGregor

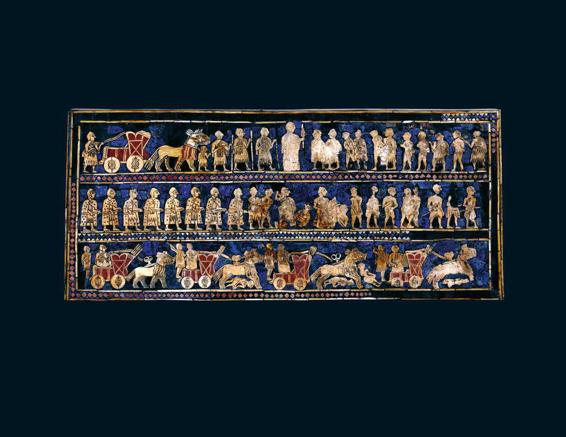

While one side of the Standard shows the ruler running a flourishing economy, the other side shows him with the army he needed to protect it. That brings me back to the thought that I began with: that it seems to be a continuous historical truth that once you get rich you then have to fight to stay rich. The king of the civil society that we see on one side has also to be the commander-in-chief we see on the other. The two faces of the Standard of Ur are in fact a superb early illustration of the military–economic nexus, of the ugly violence that frequently underlies prosperity.

War: the king reviews captured prisoners while chariots trample the enemy

Let’s look at the war scenes in more detail. Once again, the king’s head breaches the frame of the picture; he alone is shown wearing a full-length robe and he holds a large spear, while his men lead prisoners off either to their doom or to slavery. Victims and victors look surprisingly alike, because this is almost certainly a battle between close neighbours – in Mesopotamia neighbouring cities fought continually with each other for dominance. The losers are shown stripped naked to emphasize the humiliation of their defeat, and there is something heart-rending in their abject demeanour. In the bottom row are some of the oldest-known representations of chariots of war – indeed, of wheeled vehicles of any sort – and one of the first examples of what was to become a classic graphic device: the artist shows the asses pulling the chariots moving from a walk to a trot to a full gallop, gathering speed as they go. It’s a technique that no artist would better until the arrival of film.

Woolley’s discoveries at Ur in the 1920s coincided with the early years of the modern state of Iraq, created after the collapse of the Ottoman Empire at the end of the First World War. One of the key institutions of that new state was the Iraq Museum in Baghdad, which received the lion’s share of the Ur excavations. From the first moment of their discovery, there was a strong connection between the antiquities of Ur and Iraqi national identity. So the looting of antiquities from the Baghdad Museum during the recent war in Iraq was felt very profoundly by all parts of the population. Here’s Lamia al-Gailani again:

For the Iraqis, we think of it as part of the oldest civilization – which is in our country and we are descendants of it. We identify with quite a lot of the objects from the Sumerian period that have survived until now … so ancient history is really the unifying piece of Iraq today.

So Mesopotamia’s past is a key part of Iraq’s future. Archaeology and politics, like cities and warfare, seem set to remain closely connected.

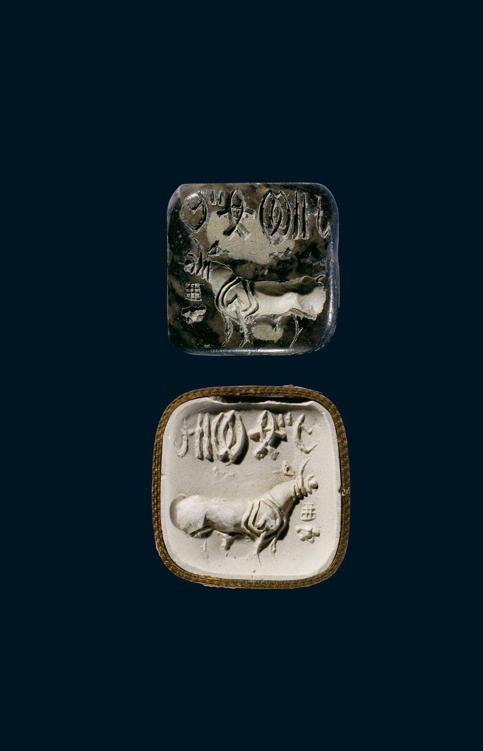

The seal mould

(top)

and an impression from it

Indus Seal

2500–2000

BC

In the last two objects we have seen the rise of the city and the state. But cities and states can also fall. I want to take you now not just to a city that was lost, but to an entire civilization that collapsed and then vanished from human memory for more than 3,500 years, largely due to climate change. Its rediscovery in Pakistan and north-west India was one of the great archaeological stories of the twentieth century; in the twenty-first we are still piecing the evidence together. This lost world was the civilization of the Indus Valley, and the story of its rediscovery begins with a small carved stone, used as a seal to stamp wet clay.

We have been exploring how the first cities and states grew up along the great rivers of the world, and how these new concentrations of people and of wealth were controlled. Around 5,000 years ago the Indus River flowed, as it still does today, down from the Tibetan Plateau into the Arabian Sea. The Indus civilization, which at its height encompassed nearly 200,000 square miles, grew up in the rich, fertile floodplains.

Excavations there have revealed plans of entire cities, as well as vigorous patterns of extensive international trade. Stone seals from the Indus Valley have been found as far afield as the Middle East and central Asia, but the seals in this chapter were found in the Indus Valley itself.

In the British Museum there is a small collection of stone seals, made to press into wax or clay in order to claim ownership, to sign a document or to mark a package. They were made between 2500 and 2000

BC

. They are all approximately square, about the size of a modern postage stamp, and they’re made of soapstone, so they were easy to carve. And they have been beautifully carved, with wonderfully incised images of animals. There’s an elephant, an ox, a kind of cross between a cow and a unicorn and, my favourite, a very skippy rhinoceros. In historical terms, the most important of them is, without question, the seal that shows a cow that looks a bit like a unicorn; it was this seal that stimulated the discovery of the entire Indus civilization.

The seal itself was discovered in the 1850s, near the town of Harappa, in what was then British India, about 150 miles south of Lahore in modern Pakistan. Over the next fifty years three more seals like it arrived in the British Museum, but no one had any idea what they were, or when and where they’d been made. But in 1906 they caught the attention of the Director-General of the Archaeological Survey of India, John Marshall. He ordered the excavation of the ruins at Harappa, where the first seal had been found. What was discovered there led to the rewriting of world history.

Marshall’s team found at Harappa the remains of an enormous city and went on to find many others nearby, all dating to between 3000 and 2000

BC

. This took Indian civilization much further back in time than anyone had previously thought. It became clear that this was a land of sophisticated urban centres, trade and industry, and even writing. It must have ranked as a contemporary and an equal with ancient Egypt or Mesopotamia – and it had been totally forgotten.

The largest of the Indus Valley cities, such as Harappa and Mohenjodaro, had populations of 30,000 to 40,000 people. They were built on rigorous grid layouts, with carefully articulated housing plans and advanced sanitation systems that even incorporated home plumbing; they’re a modern townplanner’s dream. The architect Richard Rogers admires them greatly:

When you are faced with a piece of ground where there are few limiting constraints, there are not many buildings and it’s a sort of white piece of paper, the first thing you do is start putting a grid on it, because you want to own it and a grid is a way of owning it, a way of getting order. Architecture is really giving order, harmony, beauty, rhythm to space. You can see that in Harappa; that’s exactly what they’re doing. There’s also an aesthetic element with it, which you can see from their sculpture – they have an aesthetic consciousness, and they also have a consciousness of order, and a consciousness of economy, and those things link us straight over the 5,000 years to the things that we are doing today.

As we saw in Egypt and Mesopotamia, the leap from village to city usually required one dominant ruler, able to coerce and deploy resources. But just who ran these highly ordered Indus Valley cities remains unclear. There is no evidence of kings or pharaohs – or indeed of any leader at all. This is largely because, both literally and metaphorically, we don’t know where the bodies are buried. There are none of the rich burials which in Egypt or Mesopotamia tell us so much about the powerful and about the society they controlled. We have to conclude that the Indus Valley people probably cremated their dead, and, while there may be many benefits in cremation, for archaeologists it is, if I may use the phrase, a dead loss.

What’s left of these great Indus cities gives us no indication of a society engaged with, or threatened by, war. Not many weapons have been found, and the cities show no signs of being fortified. There are great communal buildings, but nothing that looks like a royal palace, and there seems to be little difference between the homes of the rich and the poor. It seems to be a quite different model of how to create an urban civilization, without celebration of violence or extreme concentration of individual power. Is it possible that these societies were based not on coercion but on consensus?

We could find out more about the Indus civilization if only we could read the writing on our seal, and others like it. Above the animal images on the seals is a series of symbols: one looks like an oval shield; others look like matchstick human figures; there are some single lines; and there’s a standing spear shape. But whether they are numbers, logos, symbols – or even a language – we simply don’t know. Since the early 1900s people have been trying to decipher them, nowadays of course using computers, but we just do not have enough material – no longer inscriptions, no bilingual texts – to make confident progress.

The seals are often pierced, so they may have been worn by their owners, and they were probably used to stamp goods for trading – they’ve been found in Iraq, Iran, Afghanistan and central Asia. Between 3000 and 2000

BC

the Indus civilization was a vast network of complex, organized cities with flourishing trade links to the world beyond, all apparently thriving. And then, around 1900

BC

, it came to an end. The cities turned to mounds of earth, and even the memory of this, one of the great early urban cultures of the world, vanished. We can only hazard guesses as to why. The need for timber to fire the brick kilns of the huge building industry may have led to extensive deforestation and an environmental catastrophe. More importantly, climate change seems to have caused tributaries of the Indus to alter their course or to dry up completely.

When the ancient Indus civilization was initially unearthed, the entire subcontinent was under British rule, but its territory now straddles Pakistan and India. Professor Nayanjot Lahiri from Delhi University, a specialist on the Indus civilization, sums up its importance for both countries today:

In 1924, when the civilization was discovered, India was colonized. So to begin with there was a great sense of national pride and a sense that we were equal to if not better than our colonizers and, considering this, that the British should actually leave India. This is the exact sentiment that was expressed in the

Larkana Gazette

– Larkana is the district where Mohenjodaro is located.After independence the newly created state of India was left with just one Indus site in Gujarat and a couple of other sites towards the north, so there was an urgency to discover more Indus sites in India. This has been among the big achievements of Indian archaeology post-independence – that hundreds of Indus sites today are known, not only in Gujarat but also in Rajasthan, in Punjab, in Haryana and even in Uttar Pradesh.

The great cities of Harappa and Mohenjodaro, which were first excavated, are in Pakistan, and subsequently one of the most important pieces of work on the Indus civilization was done by a Pakistan archaeologist – Rafique Mughal [presently a professor at Boston University], who discovered nearly 200 sites in Pakistan and Cholistan. But my own sense is that on the whole the state of Pakistan has been much more interested, not exclusively but significantly, in its Islamic heritage, so I think there is a greater interest in India as compared to Pakistan.

There is not a competition but a certain kind of poignant sentiment that I have when I think of India, Pakistan and the Indus civilization, for no other reason than that the great remains – the artefacts, the pottery, the beads, etc., that were found at these sites – are divided between the two states. Some of the most important objects were actually divided right down the middle – like the famous girdle from Mohenjodaro. It’s no longer one object, it’s really two parts that have been sundered, like pre-independent India into India and Pakistan – these objects have met with a similar fate.