A History of the World in 100 Objects (19 page)

Read A History of the World in 100 Objects Online

Authors: Neil MacGregor

But who was wearing it? The cape is too small for a mighty warrior chief. It will fit only a slim, small person – a woman or, perhaps more likely, a teenager. The archaeologist Marie Louise Stig Sørensen highlights the role of young people in these early societies:

In the Early Bronze Age few people would live beyond about twenty-five years. Most children would not get older than five. Many women would die in childbirth, and only a few people would get very old; these very old people might have had a very special status in the society.

It’s actually difficult to know whether our concept of children applies to this society, where you very quickly became a grown-up member of the community, even if you were only ten years old, because of the average age of the communities that they lived in. That would mean that most people around then were teenagers.

This challenges our perceptions of age and responsibility. In many societies in the past, a teenager could be a parent, a full adult, a leader. So the cape may have been worn by a young person who already had considerable power. Unfortunately, the key evidence, the skeleton that was found inside the cape, was thrown away when the gold was discovered, as it clearly had no financial value. So when I look at the Mold Gold Cape now, I have a strange mix of sensations – exhilaration that such a supreme work of art has survived, and frustration that the surrounding material, which would have told us so much about this great and mysterious civilization that flourished in north Wales 4,000 years ago, was recklessly discarded.

It’s why archaeologists get so agitated about illicit excavations today. For although the precious finds will usually survive, the context which explains them will be lost, and it’s that context of material – often financially worthless – that turns treasure into history.

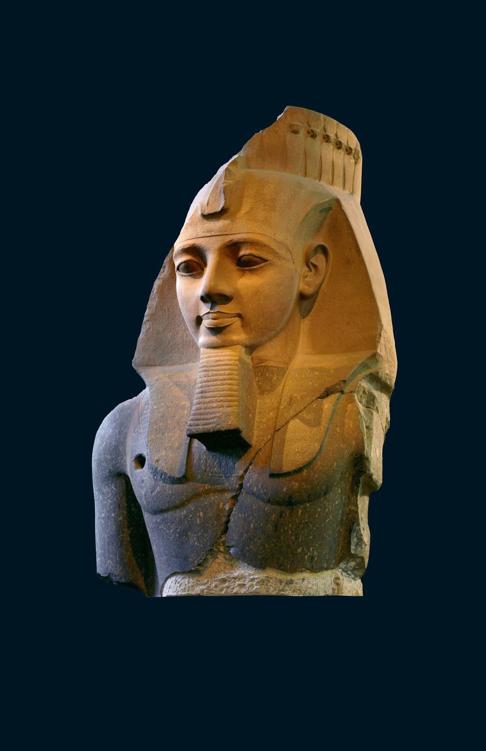

Statue of Ramesses II

AROUND

1250

BC

In 1818, the poet Percy Bysshe Shelley was inspired by a monumental figure in the British Museum to write some of his most widely quoted lines:

‘My name is Ozymandias, king of kings:

Look on my works, ye Mighty, and despair!’

Shelley’s Ozymandias is actually our Ramesses II, king of Egypt from 1279 to 1213

BC

. His giant head with a serenely commanding face looks down at visitors from a very great height, dominating the space around it.

When it arrived in England, this was by far the largest Egyptian sculpture that the British public had ever seen, and it was the first object that gave them a sense of the colossal scale of the Egyptian achievement. The upper body alone is about 2.5 metres (8 or 9 feet) high, and it weighs about 7 tonnes. This is a king who understood, as none before, the power of scale, the purpose of awe.

Ramesses II ruled Egypt for an astonishing sixty-six years, presiding over a golden age of prosperity and imperial power. He was lucky – he lived to be over 90, he fathered around a hundred children and, during his reign, the Nile floods obligingly produced a succession of bumper harvests. He was also a prodigious achiever. As soon as he took the throne in 1279

BC

he set out on military campaigns to the north and south, he covered the land with monuments, and he was seen as such a successful ruler that nine later pharaohs took his name. He was still being worshipped as a god in the time of Cleopatra, more than a thousand years later.

Ramesses was a consummate self-publicist, and a completely unscrupulous one. To save time and money he simply changed the inscriptions on pre-existing sculptures so that they bore his name and glorified his achievements. All across his kingdom he also erected vast new temples – like Abu Simbel, cut into the rocky sides of the Nile Valley. The huge image of himself there, sculpted in the rock, inspired many later imitations, not least the vast faces of American presidents carved into Mount Rushmore.

In the far north of Egypt, facing towards neighbouring powers in the Near East and the Mediterranean, he founded a new capital city, modestly called Pi-Ramesses Aa-nakhtu, the ‘House of Ramesses II, Great and Victorious’. One of his proudest achievements was his memorial complex at Thebes, near modern Luxor. It wasn’t a tomb where he was going to be buried, but a temple where he would be venerated in life and then worshipped as a god for all eternity. The Ramesseum, as it’s now known, covers an immense area, about the size of four football pitches, and contained temple, palace and treasuries.

There were two courtyards in the Ramesseum, and our statue sat at the entrance to the second one. But, magnificent though it is, this statue was just one of many – Ramesses was replicated again and again throughout the complex, a multiple vision of monumental power that must have had an overwhelming effect on the officials and priests who went there. The sculptor Antony Gormley, who created the Angel of the North, places such monumental sculpture in context:

For me as a sculptor the acceptance of the material as a means of conveying the relationship between human-lived biological time and the aeons of geological time is an essential condition of the waiting quality of sculpture. Sculptures persist, endure, and life dies. And all Egyptian sculpture in some senses has this dialogue with death, with that which lies on the other side.

There is something very humbling, a celebration of what a people can do together, because that is the other extraordinary thing about Egyptian architecture and sculpture, which were engaged upon by vast numbers of people, and which were a collective act of celebration of what they were able to achieve.

It is an important point. This serenely smiling sculpture is not the creation of an individual artist, but the achievement of a whole society – the result of a huge, complex process of engineering and logistics – in many ways much closer to building a motorway than making a work of art.

The granite for the sculpture was quarried from Aswan, more than 150 kilometres (90 miles) up the Nile to the south, and extracted in a single colossal block – the whole statue would have originally weighed about 20 tonnes. It was then roughly shaped before being moved on wooden sleds, pulled by large teams of labourers, from the quarry to a raft which was floated down the Nile to Luxor. The stone was then hauled from the river to the Ramesseum, where the finer stone-working took place. An enormous amount of man-power and organization was needed to erect even this one statue, and the whole workforce had to be trained, managed, coordinated and, if not paid – many of them would have been slaves – at least fed and housed. To deliver our sculpture a literate, numerate and very well-oiled bureaucratic machine was essential – and that same machine was also used to manage Egypt’s international trade and to organize and equip its armies.

Ramesses undoubtedly had both great ability and real successes, but, like all supreme masters of propaganda, where he didn’t actually succeed he just made it up. He was not exceptional in combat, but he was able to mobilize a considerable army and supply them with ample weaponry and equipment. Whatever the actual result of his battles, the official line was always the same – Ramesses triumphs. The whole of the Ramesseum conveyed a consistent message of imperturbable success. Here is the Egyptologist Dr Karen Exell, on Ramesses the propagandist:

He very much understood that being visible was central to the success of the kingship, so he put up as many colossal statues as he could, very quickly. He built temples to the traditional gods of Egypt, and this kind of activity has been interpreted as being bombastic – showing off and so on – but we really need to see it in the context of the requirements of the kingship. People needed a strong leader, and they understood a strong leader to be a king who was out there campaigning on behalf of Egypt and was very visible within Egypt. We can even look at what we can regard as the ‘spin’ of the records of the battle of Qadesh in his year five, which was a draw. He came back to Egypt and had the record of this battle inscribed on seven temples, and it was presented as an extraordinary success, that he alone had defeated the Hittites. So it was all spin, and he completely understood how to use that.

This king would not only convince his own people of his greatness: he would also fix the image of imperial Egypt for the whole world. Later, Europeans were mesmerized. Around 1800 the competing aggressive powers in the Middle East, then the French and the British, vied with each other to acquire the image of Ramesses. Napoleon’s men tried to remove the statue from the Ramesseum in 1798, but failed. There is a hole about the size of a tennis ball drilled into the torso, just above the right breast, which experts think came from this attempt. By 1799 the statue had been broken.

In 1816 the bust was successfully removed, rather appropriately, by a circus-strongman-turned-antiquities-dealer named Giovanni Battista Belzoni. Using a specially designed system of hydraulics Belzoni organized hundreds of workmen to pull the bust on wooden rollers, by ropes, to the banks of the Nile, almost exactly the method used to bring it to the Ramesseum in the first place. It is a powerful demonstration of Ramesses’ achievement that moving just half the statue was considered a great technical feat 3,000 years later. Belzoni then loaded the bust on to a boat, and the dramatic cargo went from there to Cairo, to Alexandria, and then finally to London. On arrival, it astounded everybody who saw it and began a revolution in how we Europeans view the history of our culture. The Ramesses in the British Museum was one of the first works to challenge long-held assumptions that great art had begun in Greece.

Ramesses’ success lay not only in maintaining the supremacy of the Egyptian state, through the smooth running of its trade networks and taxation systems, but also in using the rich proceeds for building numerous temples and monuments. His purpose was to create a legacy that would speak to all generations of his eternal greatness. Yet, by the most poetic of ironies, his statue has come to mean exactly the opposite.

Shelley heard reports of the discovery of the bust and of its transportation to England. He was inspired by accounts of its colossal scale, but he also knew what had happened to Egypt after Ramesses – with the crown passing to Libyans and Nubians, Persians and Macedonians, and Ramesses’ statue itself squabbled over by the recent European intruders. As Antony Gormley puts it, sculptures endure, and life dies; Shelley’s poem ‘Ozymandias’ is a meditation not on imperial grandeur but on the transience of earthly power, and in it Ramesses’ statue becomes a symbol of the futility of all human achievement.

‘My name is Ozymandias, king of kings:

Look on my works, ye Mighty, and despair!’

Nothing beside remains. Round the decay

Of that colossal wreck, boundless and bare

The lone and level sands stretch far away.

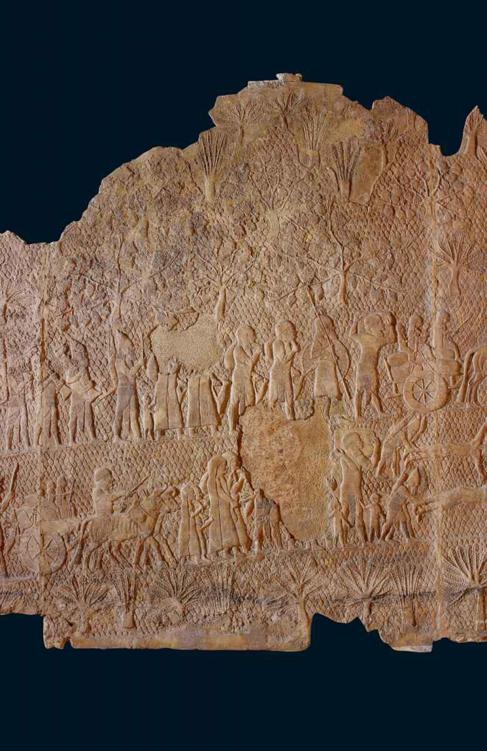

Old World, New Powers

1100–300

BC

About 1000

BC

new powers arose in several parts of the world, overwhelmed the existing order, and took its place. Warfare was conducted on an entirely new scale. Egypt was challenged by its former subject peoples from Sudan; in Iraq a new military power, the Assyrians, built an empire that eventually covered much of the Middle East; and in China, a group of outsiders, the Zhou, overthrew the long-established Shang Dynasty. There were also profound changes in economic behaviour: in both what is now Turkey and China coins were used for the first time, leading to a rapid growth of commercial activity. Meanwhile, quite separately, the first cities and complex societies in South America began to emerge.