A History of the World in 100 Objects (69 page)

Read A History of the World in 100 Objects Online

Authors: Neil MacGregor

Tolerance and Intolerance

AD

1550–1700

The Protestant Reformation split the western Christian Church into two rival factions and triggered major religious wars. The failure of either side to achieve victory in the Thirty Years War would lead, through exhaustion, to a period of religious tolerance in Europe. Three great Islamic powers dominated Eurasia: the Ottomans in Turkey, the Mughals in India and the Safavids in Iran. The Mughals promoted religious tolerance, allowing the Indian subcontinent’s largely non-Islamic population to continue to worship as they pleased. In Iran the Safavids created the world’s first major Shi’a state. At the same time, conquest and trade redrew the religious map of the world, and both Catholicism in the Americas and Islam in south-east Asia sought to accommodate the existing rituals of their new converts.

Shi’a Religious Parade Standard

AD

1650–1700

It comes as a surprise to most tourists visiting Isfahan, the capital of Shi’a Iran in the seventeenth century, to discover in that very Islamic city one of the world’s great Christian cathedrals, full of silver crucifixes and wall-paintings telling the narratives of biblical redemption. This cathedral was built in the first half of the seventeenth century by Shah Abbas I, the great ruler of early modern Iran, and provides a superb example of how the world map of religion was redrawn in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries. The question at the centre of that redrawing was whether a state could hold more than one faith; the answer to it, in sixteenth-and seventeenth century Iran, was that it most certainly could. But the monotheistic faiths have always found it difficult to live together for long, and religious tolerance among them is usually both contested and fragile. In this chapter I will be exploring the situation in seventeenth-century Iran through an ‘alam – a lavishly gilded ceremonial brass standard. ‘Alams were originally battle standards, designed to be carried like flags into the fight, but in seventeenth-century Iran they were used in great religious processions and rallied not warriors but the faithful.

Shah Abbas was a member of the Safavid Dynasty, which came to power around 1500 and established Shi’a Islam as the state religion of Iran, a position it has held ever since. There is an interesting parallel with events in Tudor England, which became officially Protestant at about the same time as Iran became Shi’a. In both countries religion became a defining element of national identity, setting the nation apart from its hostile neighbours – Protestant England from Catholic Spain, Shi’a Iran from its Sunni neighbours, above all Turkey.

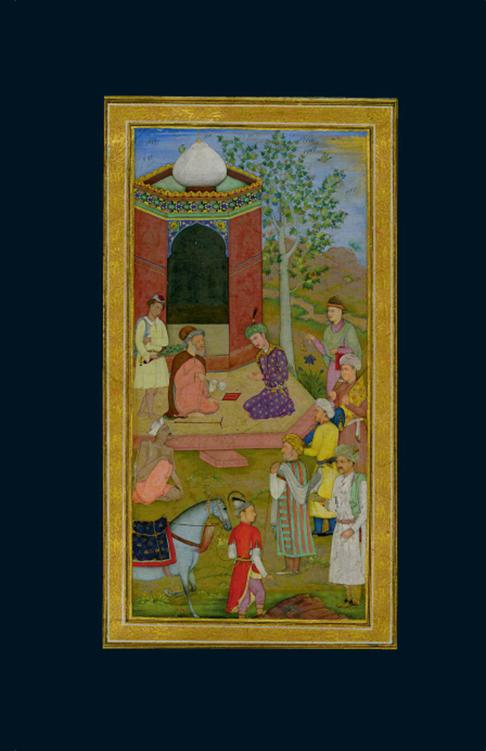

Shah Abbas, a contemporary of Elizabeth I of England, was a ruler of rare political nous and even rarer religious pragmatism. Like Elizabeth, he was keen to develop international trade and contact. He invited the world to visit his capital in Isfahan, welcoming Chinese envoys at the same time as hiring Englishmen as advisers; he expanded his borders and in the process captured Armenian Christians whom he brought back to Isfahan. There the Armenians developed the highly profitable trade in silks and textiles with the Middle East and Europe, and in return Shah Abbas built for them a Christian cathedral. Visiting Europeans were astonished by this active religious tolerance, with Christians and Jews, each with their own places of worship, peacefully accommodated within a Muslim state – a level of religious diversity unthinkable in Christian Europe at the time. Isfahan was of course a centre for Islamic scholarship and a place where architecture, painting and high craft in silks, ceramics and metalwork were all put to the service of the faith.

The names of the family of the Prophet are written above the central mihrab of the Mosque of Shaykh Lutfallah

This Shi’a Iran of the Safavid shahs, sophisticated and cosmopolitan, prosperous and devout, which lasted for more than 200 years, can still be seen in this ‘alam, made around 1700. It is approximately sword-shaped, with a disc between the blade and the handle, and is 127 centimetres (50 inches) high. It is made of gilded brass typical of the metalworking tradition that had evolved in Iran and especially in Isfahan, where merchants and craftsmen from India, the Near East and Europe met and traded.

But however cosmopolitan the style and skill, this ‘alam was made specifically for use in a Shi’a Muslim ceremony, mounted on a long pole and carried high in procession through the streets. The blade of the sword has been transformed into a filigree of words and patterns. The words are effectively a declaration of faith, and words like this are part of the physical fabric of Shi’a Isfahan.

The Mosque of Shaykh Lutfallah was built by Shah Abbas at the same time as he built the cathedral for the Christians. It is a monument to the word: the structural elements of the architecture are all marked out and decorated with inscriptions, the words of God, the words of the Prophet or other holy texts. In fact, the words appear to hold the building up. Over the mihrab, the central niche, which marks the direction of Mecca towards which the faithful should pray, are written the names of the Ahl al-Bayt, the family of the house – that is, the family of the Prophet. There are the names of the Prophet Muhammad himself, Fatima, the Prophet’s daughter, her husband Ali, and their sons Hassan and Husain.

Isfahan Cathedral, built in the first half of the seventeenth century by Shah Abbas I, combines Christian iconography with Islamic design

We find the same names on the ‘alam in the British Museum’s galleries. Ali is mentioned three times. For Shi’a Muslims, Ali was the first imam, or spiritual leader, of the faithful, and this kind of ‘alam is known as ‘The Sword of Ali’. Elsewhere on the ‘alam are the names of the ten other Shi’a imams – all descended from Ali and all, like him, martyred. As this ‘alam was carried through the streets the faithful would see the names of the Prophet, of Fatima, of Ali and of all the other imams.

Shi’ites hold that the office of imam – infallible religious guide – belongs to the house of Muhammad alone and so to the descendants of Ali, the Prophet’s son-in-law. By contrast, the majority of Sunni Muslims accepted the authority of the caliph, originally an elected office. In the decades after the Prophet’s death, these differing views led to bloody conflict, during which Ali and his sons were all killed – the beginning of a tradition of martyred Shi’a imams.

The Shi’ism of the Safavids was

Ithna ‘Ashari

, or Twelver Shi’ism, which holds that there are twelve imams, of whom eleven died as martyrs and are named on the ‘alam itself. The Twelfth Imam is said to have vanished in 873 and to be in hiding, awaited by the faithful and to be restored by God when it pleases him, at which point Shi’a dominion will be established on earth. Until then, the Safavid shahs, who also claimed descent from the Prophet, were the temporary proxy for the hidden imam. Authority in religious matters, however, lay not with the shah, but with the ulema – the body of Islamic scholars and jurists responsible for interpreting Islamic law, as indeed they still are today.

Haleh Afshar, an Iranian-born academic, reflects on the position of Shi’ism in the life and politics of Iran over the centuries, and its role in both the Constitutional Revolution of 1907 and the Islamic Revolution of 1979:

Shi’ism for centuries was the small part of Islam that was very different and a group which was not a part of any establishment. In fact Shi’ites were always in the process of contestation and on the margins. With the arrival of the Safavids, who declared Shi’ism as the national religion of Iran, we begin to have the establishment of a religious institution with a hierarchy and one that has some kind of influence on policy. That is something quite new in terms of Iranian history. It is a process that has continued through the centuries, and the religious establishment very often has been at the forefront of revolutions, for example the Constitutional Revolution in 1907, in which religious leaders were demanding the establishment of a house of justice and a constitution, and also the 1979 revolution, again in the name of justice, which is a constant theme at the core of Shi’ism.

This heightened sense of justice perhaps has its roots in the very essence of Shi’ism – its focus on victims and martyrs. By the late seventeenth century, when this ‘alam was made, elaborate ceremonial processions commemorating the deaths of the martyrs featured chain-swinging flagellants, rhythmic movement, music and chanting. This illustrates the paradoxical nature of the British Museum’s ‘alam. Sword-like in form and name and thus at first sight triumphalist and aggressive, it was in fact used in Shi’a ceremonies that commemorated defeat, suffering and martyrdom.

Present-day ‘alams are sometimes enormous. No longer a single blade of metal, they are great structures covered in decorated cloth, which can span a whole road’s width – and yet they are often borne by one man.

We spoke to one of the elders of the Iranian community in north-west London, Hossein Pourtahmasbi, who describes how the tradition of carrying ‘alams continues today:

First of all you have to be a good weightlifter, because it’s quite heavy. It sometimes goes up to 100 kilograms, but it’s not just a matter of weight – it’s the balancing and unbalancing shape of the ‘alam, which is huge and wide. You have to be very physically fit for that, and the people are either wrestlers or weightlifters and physically strong and well known by that society. But to be a strong man is not enough: in that community the people have got to know you as well, because it’s tradition that gives you admission. It’s keeping the memory alive, and it keeps you strong; you keep singing the songs, keeping the tradition and carry on!

By the time our ‘alam was made, around 1700, this kind of muscular fervour had become a key element of Shi’a ceremonies. But the equilibrium between different faiths achieved by Shah Abbas was abandoned by his successors. The last Safavid shah, Husayn, was harshly intolerant of non-Shi’ites and gave religious leaders extensive powers to regulate public behaviour, a religious repression that may have contributed to his downfall. In 1722 Husayn was overthrown, the long Safavid era ended, and Iran condemned to several decades of political chaos. But the legacy of Shah Abbas is still evident in Iran today. The state is officially Shi’a, but Christians, Jews and Zoroastrians are all by the terms of the Constitution free to practise their religion in public. As in the seventeenth century, Iran is still a multi-faith society, with a tolerance of religious difference that surprises and impresses many visitors.