A History of the World in 6 Glasses (13 page)

Read A History of the World in 6 Glasses Online

Authors: Tom Standage

At the same time, London was emerging as the hub of a thriving commercial empire. The embrace of coffeehouses by businessmen, for whom they provided convenient and respectable public places in which to meet and do business, ensured their continued popularity after the Restoration. By appealing to Puritans, plotters, and capitalists alike, London's coffeehouses matched the city's mood perfectly.

The city's first coffeehouse was opened in 1652 by Pasqua Rosee, the Armenian servant of an English merchant named Daniel Edwards who had acquired a taste for coffee while traveling in the Middle East. Edwards introduced his friends in London to coffee, which Rosee would prepare for him several times a day. So enthusiastic were they for the new drink that Edwards decided to set Rosee up in business as a coffee seller. The handbill announcing the launch of Rosee's business, titled

The Vertue of the Coffee Drink,

shows just how much of a novelty coffee was. It assumes total ignorance of coffee on the part of the reader, explaining the drink's origins in Arabia, the method of its preparation, and the customs associated with its consumption. Much of the handbill was concerned with coffee's supposed medicinal qualities. It was said to be effective against sore eyes, headache, coughs, dropsy, gout, and scurvy, and to prevent "Mis-carryings in Child-bearing Women." But it was perhaps the explanation of the commercial benefits of coffee that drew Rosee's customers in: "It will prevent Drowsiness, and make one fit for business, if one have occasion to Watch; and therefore you are not to Drink of it after Supper, unless you intend to be watchful, for it will hinder sleep for 3 or 4 hours."

Such was Rosee's success that the local tavern keepers protested to the lord mayor that Rosee had no right to set up a business in competition with them, since he was not a freeman of the City. Rosee was ultimately forced out of the country, but the idea of the coffeehouse had taken hold, and further examples sprung up during the 1650s. By 1663 the number of coffeehouses in London had reached eighty-three. Many of them were destroyed in the Great Fire of London in 1666, but even more arose in their place, and by the end of the century there were hundreds of them. One authority puts the total at three thousand, though that seems unlikely in a city with a population of just six hundred thousand at the time. (Coffeehouses sometimes served other drinks too, such as hot chocolate and tea, but their orderly and convivial atmosphere was inspired by Arabian coffeehouses, and coffee was the predominant drink.)

Not everyone approved, however. Alongside the tavern keepers and vintners, who had commercial reasons for objecting to coffee, the drink's opponents included medical men who believed the new drink was poisonous and commentators who, echoing Arab critics of coffee, worried that coffeehouses encouraged time-wasting and trivial discussion at the expense of more important activities. Others simply objected to the taste of coffee, which was disparaged as "syrup of soot" or "essence of old shoes." (Coffee, like beer, was taxed by the gallon, which meant it had to be made up in advance. Cold coffee from a barrel was then reboiled before serving, which cannot have done much for the taste.)

The result was a stream of pamphlets and broadsides on both sides of the debate, with such titles as

A Coffee Scuffle

(1662),

A Broadside Against Coffee

(1672),

In Defence of Coffee

(1674), and

Coffee Houses Vindicated

(1675). One notable attack on London's coffeehouses came from a group of women, who published

The Women's Petition Against Coffee, representing to public consideration the grand inconveniences accruing to their sex from the excessive use of the drying and enfeebling Liquor.

The women complained that their husbands were drinking so much coffee that they were becoming "as unfruitful as the deserts, from where that unhappy berry is said to be brought." Furthermore, since the men were spending all their time in coffeehouses, from which women were prohibited, "the whole race was in danger of extinction."

The simmering debate over the merits of coffee prompted the British authorities to act. King Charles II had, in fact, been looking for a pretext to move against the coffeehouses for some time. Like his counterparts in the Arab world, he was suspicious of the freedom of speech allowed in coffeehouses and their suitability for hatching plots. Charles was particularly aware of this, since coffeehouse machinations had played a small part in his own accession to the throne. On December 29, 1675, the king issued a "Proclamation for the suppression of Coffee-houses," declaring that since such establishments "have produced very evil and dangerous effects . . . for that in such Houses . . . divers False, Malitious and Scandalous Reports are devised and spread abroad, to the Defamation of His Majestie's Government, and to the Disturbance of the Peace and Quiet of the Realm; His Majesty hath thought it fit and necessary, That the said Coffee-Houses be (for the future) Put down and Suppressed."

The result was a public outcry, for coffeehouses had by this time become central to social, commercial, and political life in London. When it became clear that the proclamation would be widely ignored, which would undermine the government's authority, a further proclamation was issued, announcing that coffee sellers would be allowed to stay in business for six months if they paid five hundred pounds and agreed to swear an oath of allegiance. But the fee and time limit were soon dropped in favor of vague demands that coffeehouses should refuse entry to spies and mischief makers. Not even the king could halt the march of the coffee.

Similarly, doctors in Marseilles, where France's first coffeehouse had opened in 1671, attacked coffee on health grounds at the behest of wine merchants who feared for their livelihood. Coffee, they declared, was a "vile and worthless foreign novelty . . . the fruit of a tree discovered by goats and camels [which] burned up the blood, induced palsies, impotence and leanness" and would be "hurtful to the greater part of the inhabitants of Marseilles." But this attack did little to slow the spread of coffee; it had already caught on as a fashionable drink among the aristocracy, and coffeehouses were flourishing in Paris by the end of the century. When coffee became popular in Germany, the composer Johann Sebastian Bach wrote a "Coffee Cantata" satirizing those who unsuccessfully opposed coffee on medical grounds. Coffee was also embraced in Holland, where one writer observed in the early eighteenth century that "its use has become so common in our country that unless the maids and seamstresses have their coffee every morning, the thread will not go through the eye of the needle." The Arab drink had conquered Europe.

Empires of Coffee

Until the end of the seventeenth century, Arabia was unchallenged as supplier of coffee to the world. As one Parisian writer explained in 1696, "Coffee is harvested in the neighbourhood of Mecca. Thence it is conveyed to the port of Jiddah. Hence it is shipped to Suez, and transported by camels to Alexandria. Here, in the Egyptian warehouses, French and Venetian merchants buy the stock of coffee-beans they require for their respective homelands." Coffee was also shipped, on occasion, directly from Mocha by the Dutch. But as coffee's popularity grew, European countries began to worry about their dependency on this foreign product and set about establishing their own supplies. The Arabs understandably did everything they could to protect their monopoly. Coffee beans were treated before being shipped to ensure they were sterile and could not be used to seed new coffee plants; foreigners were excluded from coffee-producing areas.

First to break the Arab monopoly were the Dutch, who displaced the Portuguese as the dominant European nation in the East Indies during the seventeenth century, gaining control of the spice trade in the process and briefly becoming the world's leading commercial power. Dutch sailors purloined cuttings from Arab coffee trees, which were taken to Amsterdam and successfully cultivated in greenhouses. In the 1690s coffee plantations were established by the Dutch East India Company at Batavia in Java, an island colony in what is now Indonesia. Within a few years, Java coffee shipped directly to Rotterdam had granted the Dutch control of the coffee market. Arabian coffee was unable to compete on price, though connoisseurs thought its flavor was superior.

Next came the French. The Dutch had helpfully demonstrated that coffee flourished in a similar climate to that required by sugar, which suggested that it would grow as well in the West Indies as it did in the East Indies. A Frenchman, Gabriel Mathieu de Clieu, who was a naval officer stationed on the French island of Martinique, took it upon himself to introduce coffee to the French West Indies. During a visit to Paris in 1723, he embarked on an entirely unofficial scheme to get hold of a cutting of a coffee tree to take back to Martinique. The only coffee tree in Paris was a well-guarded specimen in a greenhouse in the Jardin des Plantes, presented by the Dutch as a gift to Louis XIV in 1714; Louis, however, seems to have taken little interest in coffee. De Clieu could not simply help himself to a cutting from this royal tree, so he used his connections instead. He prevailed upon an aristocratic young lady to obtain a cutting from the royal doctor, who was entitled to use whatever plants he wanted in the preparation of medical remedies. This cutting was then passed back to de Clieu, who tended it carefully and took it, installed in a glass box, onto a ship bound for the West Indies.

If de Clieu's self-aggrandizing account is to be believed, the plant faced numerous dangers on its journey across the Atlantic. "It is useless to recount in detail the infinite care that I was obliged to bestow upon this delicate plant during a long voyage, and the difficulties I had in saving it," de Clieu wrote many years later, at the start of a detailed account of his perilous journey. First the plant had to brave the attentions of a mysterious passenger who spoke French with a Dutch accent. Every day de Clieu would carry his plant on deck to expose it to the sun, and after dozing next to his plant one day he awoke to find the Dutchman had snapped off one of its shoots. The Dutchman, however, disembarked at Madeira. The ship then had a brush with a pirate corsair and only narrowly escaped. The coffee plant's glass box was damaged in the fight, so de Clieu had to ask the ship's carpenter to repair it for him. Then followed a storm, which again damaged the box and soaked the plant with seawater. Finally, the ship was becalmed for several days, and drinking water had to be rationed. "Water was lacking to such an extent that for more than a month I was obliged to share the scanty ration of it assigned to me with my coffee plant, upon which my happiest hopes were founded," de Clieu wrote.

Eventually, de Clieu and his precious cargo arrived at Martinique. "Arriving at home my first care was to set out my plant with great attention in the part of my garden most favorable to its growth," he wrote. "Although keeping it in view, I feared many times that it would be taken from me; and I was at last obliged to surround it with thorn bushes and to establish a guard about it until it arrived at maturity . . . this precious plant which had become still more dear to me for the dangers it had run and the cares it had cost me." Two years later, de Clieu gathered his first harvest from the plant. He then began to give cuttings of the plant to his friends, so that they could begin cultivation too. De Clieu also sent coffee plants to the islands of Santo Domingo and Guadeloupe, where they flourished. Coffee exports to France began in 1730, and production so exceeded domestic demand that the French began shipping the excess coffee from Marseilles to the Levant. Once again, Arabian coffee found it difficult to compete. In recognition of his achievement, de Clieu was presented in 1746 to Louis XV, who was keener on coffee than his predecessor had been. At around the same time, the Dutch introduced coffee to Suriname, a colony in South America. Descendants of de Clieu's original plant were also proliferating in the region, in Haiti, Cuba, Costa Rica, and Venezuela. Ultimately, Brazil became the world's dominant coffee supplier, leaving Arabia far behind.

Gabriel Mathieu de Clieu shares his water ration with his coffee plant, while becalmed en route to Martinique.

Coffee had come a long way from its obscure origins as a religious drink in Yemen. After permeating the Arab world, it had been embraced throughout Europe and was then spread around the world by European powers. Coffee had come to worldwide prominence as an alternative to alcohol, chiefly favored by intellectuals and businessmen. But of even greater significance than this new drink was the novel way in which it was consumed: in coffeehouses, which dispensed conversation as much as coffee. In doing so, coffeehouses provided an entirely new environment for social, intellectual, commercial, and political exchange.

The Coffeehouse Internet

You that delight in Wit and Mirth, and long to hear such News,

As comes from all parts of the Earth, Dutch, Danes, and Turksand Jews,

I'le send you a Rendezvous, where it is smoaking new: Go hear it at a Coffee-house—it cannot but be true . . .

There's nothing done in all the World, From Monarch to the Mouse,

But every Day or Night 'tis hurl'd into the Coffee-house.

—

from "News from the Coffee-House"

by Thomas Jordan (1667)

A Coffee-Powered Network

W

HEN A SEVENTEENTH-CENTURY European businessman wanted to hear the latest business news, follow commodity prices, keep up with political gossip, find out what other people thought of a new book, or stay abreast of the latest scientific developments, all he had to do was walk into a coffeehouse. There, for the price of a cup (or "dish") of coffee, he could read the latest pamphlets and newsletters, chat with other patrons, strike business deals, or take part in literary or political discussions. Europe's coffeehouses functioned as information exchanges for scientists, businessmen, writers, and politicians. Like modern Web sites, they were vibrant and often unreliable sources of information, typically specializing in a particular topic or political viewpoint. They became the natural outlets for a stream of newsletters, pamphlets, advertising free-sheets, and broadsides. One contemporary observer noted: "The Coffee-houses particularly are very commodious for a free Conversation, and for reading at an easie Rate all manner of printed News, the Votes of Parliament when sitting, and other Prints that come out Weekly or casually. Amongst which the London Gazette comes out on Mundays and Thursdays, the Daily Courant every day but Sunday, the Postman, Flying-Post, and Post-Boy, Tuesdays, Thursdays, and Saturdays, and the English Post, Mundays, Wednesdays, and Fridays; besides their frequent Postscripts." These publications also carried coffeehouse wit out into the provinces and country towns.

Depending on the interests of their customers, some coffeehouses displayed commodity prices, share prices, or shipping lists on their walls; others subscribed to foreign newsletters filled with news from other countries. Coffeehouses became associated with specific trades, acting as meeting places where actors, musicians, or sailors could go if they were looking for work. Coffeehouses catering to a particular clientele, or dedicated to a given subject, were often clustered together in the same neighborhood.

This was especially true in London, where hundreds of coffeehouses, each with its own distinctive name and sign over the door, had been established by 1700. Those around St. James's and Westminster were frequented by politicians; those near St. Paul's Cathedral by clergymen and theologians. The literary set, meanwhile, congregated at Will's coffeehouse in Covent Garden, where for three decades the poet John Dryden and his circle reviewed and discussed the latest poems and plays. The coffeehouses around the Royal Exchange were thronged with businessmen, who would keep regular hours at particular coffeehouses so that their associates would know where to find them, and who used coffeehouses as offices, meeting rooms, and venues for trade. Books were sold at Man's coffeehouse in Chancery Lane, and goods of all kinds were bought and sold in several coffeehouses that doubled as auction rooms. So closely were some coffeehouses associated with certain topics that the

Tatler,

a London magazine founded in 1709, used the names of coffeehouses as subject headings for its articles. Its first issue declared: "All accounts of Gallantry, Pleasure, and Entertainment shall be under the Article of White's Chocolate-house; Poetry, under that of Will's Coffee-house; Learning, under the title of Grecian; Foreign and Domestick News, you will have from St. James's Coffee-house."

Richard Steele, the

Tatler's

editor, gave its postal address as the Grecian coffeehouse, the preferred haunt of the scientific community. This was another coffeehouse innovation: After the establishment of the London penny post in 1680, it became a common practice to use a coffeehouse as a mailing address. Regulars at a particular coffeehouse could pop in once or twice a day, drink a dish of coffee, hear the latest news, and check to see if there was any new mail waiting for them. "Foreigners remarked that the coffee-house was that which especially distinguished London from all other cities," wrote the nineteenth-century historian Thomas Macauley in his

History of England.

"The coffee-house was the Londoner's home, and that those who wished to find a gentleman commonly asked, not whether he lived in Fleet Street or Chancery Lane, but whether he frequented the Grecian or the Rainbow." Some people frequented multiple coffeehouses, the choice of which depended on their interests. A merchant, for example, might oscillate between a financial coffeehouse and one specializing in Baltic, West Indian, or East Indian shipping. The wide-ranging interests of the English scientist Robert Hooke were reflected in his visits to around sixty London coffeehouses during the 1670s, as recorded in his diary.

Rumors, news, and gossip were carried between coffeehouses by their patrons, and on occasion runners would flit from one coffeehouse to another to report major events such as the outbreak of war or the death of a head of state. ("The Grand Vizier strangled," noted Hooke after learning the news at Jonathan's coffeehouse on May 8, 1693.) News traveled fast across this coffee-powered network; according to one account published in the

Spectator

in 1712: "There was a fellow in town some years ago, who used to divert himself by telling a lye at Charing Cross in the morning at eight of the clock, and then following it through all parts of town until eight at night; at which time he came to a club of his friends, and diverted them with an account [of] what censure it had drawn at Will's in Covent Garden, how dangerous it was believed at Child's and what inference they drew from it with relation to stocks at Jonathan's."

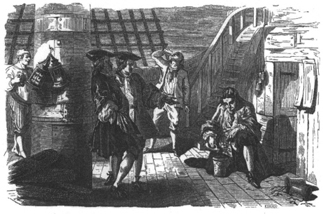

A coffeehouse in late-seventeenth-century London

Coffeehouse discussions both molded and reflected public opinion, forming a unique bridge between the public and private worlds. In theory, coffeehouses were public places, open to any man (since women were excluded, at least in London); but their homely decor and comfortable furniture, and the presence of regular customers, also gave them a cosy, domestic air. Patrons were expected to respect certain rules that did not apply in the outside world. According to custom, social differences were to be left at the coffeehouse door; in the words of one contemporary rhyme, "Gentry, tradesmen, all are welcome hither, and may without affront sit down together." The alcohol-related practice of toasting to other people's health was banned, and anyone who started a quarrel had to atone for it by buying a dish of coffee for everyone present.

The significance of coffeehouses was most readily apparent in London, a city that, between 1680 and 1730, consumed more coffee than anywhere else on Earth. The diaries of intellectuals of the time are littered with coffeehouse references: "Thence to the coffee-house" appears frequently in the celebrated diary of Samuel Pepys, an English public official. His entry for January 11, 1664, gives a flavor of the cosmopolitan, serendipitous atmosphere that prevailed within the coffeehouses of the period, where matters both profound and trivial were discussed, and you never knew who you might meet, or what you might hear: "Thence to the Coffee-house, whither comes Sir W. Petty and Captain Grant, and we fell in talke (besides a young gentleman, I suppose a merchant, his name Mr. Hill, that has travelled and I perceive is a master in most sorts of musique and other things) of musique; the universal character; art of memory . . . and other most excellent discourses to my great content, having not been in so good company a great while, and had I time I should covet the acquaintance of that Mr. Hill. . . . The general talke of the towne still is of Col-lonell Turner, about the robbery; who, it is thought, will be hanged."

Similarly, Hooke's diary shows that he used coffeehouses as places for academic discussions with friends, negotiations with builders and instrument makers, and even as venues for scientific experiments. One entry from February 1674 notes the subjects of discussion at Garraway's, his preferred coffeehouse at the time: the supposed custom, among tradesmen in the Indies, to hold things with their feet as well as their hands; the prodigious height of palm trees; and "the extreme deliciousness of the queen pine apple," then a new and exotic fruit from the West Indies.

Coffeehouses were centers of self-education, literary and philosophical speculation, commercial innovation, and, in some cases, political fermentation. But above all they were clearinghouses for news and gossip, linked by the circulation of customers, publications, and information from one establishment to the next. Collectively, Europe's coffeehouses functioned as the Internet of the Age of Reason.

Innovation and Speculation

The first coffeehouse in western Europe opened not in a center of trade or commerce but in the university city of Oxford, where a Lebanese man named Jacob set up shop in 1650, two years before Pasqua Rosee's London establishment. Although the connection between coffee and academia is now taken for granted—coffee is the drink customarily served in between sessions at academic conferences and symposia—it was initially controversial. When coffee became popular in Oxford and the coffeehouses selling it began to multiply, the university authorities tried to clamp down, worrying that coffeehouses promoted idleness and distracted members of the university from their studies. Anthony Wood, a chronicler of the time, was among those who denounced the enthusiasm for the new drink. "Why doth solid and serious learning decline, and few or none follow it now in the university?" he asked. "Answer: Because of coffee-houses, where they spend all their time." But coffee's opponents could not have been more wrong, for coffeehouses became popular venues for academic discussion, particularly among those who took an interest in the progress of science, or "natural philosophy" as it was known at the time. Far from discouraging intellectual activity, coffee actively promoted it. Indeed, coffeehouses were sometimes called "penny universities," since anyone could enter and join the discussion for a penny or two, the price of a dish of coffee. As one ditty of the time put it: "So great a Universitie, I think there ne'er was any; In which you may a Scholar be, for spending of a Penny."

One of the young men who acquired a taste for coffeehouse discussions while studying at Oxford was the English architect and scientist Christopher Wren. Chiefly remembered today as the architect of St. Paul's Cathedral in London, Wren was also one of the leading scientists of his day. He was a founding member of the Royal Society, Britain's pioneering scientific institution, which was formed in London in 1660. Its members, including Hooke, Pepys, and Edmond Halley (the astronomer after whom the comet is named), would often decamp to a coffeehouse after the society's meetings to continue their discussions. To give a typical example, on May 7, 1674, Hooke recorded in his diary that he demonstrated an improved form of astronomical quadrant at the Royal Society, and repeated his demonstration afterward at Garraway's coffeehouse, where he discussed it with John Flamsteed, an astronomer appointed by Charles II as the first astronomer royal the following year. In contrast with the formal atmosphere of the society's meetings, coffeehouses provided a more relaxed atmosphere which encouraged discussion, speculation, and exchange of ideas.

Hooke's diary gives examples of how information could be exchanged in coffeehouse discussions. At one meeting, at Man's coffeehouse, Hooke and Wren traded information about the behavior of springs. "Discoursed much about Demonstration of spring motion. He told a pretty thought of his about a poysd weather glass. . . . I told him an other. . . . I told him my philo-sophicall spring scales. . . . He told me his mechanick rope scale." On another occasion Hooke exchanged recipes for medical remedies with a friend at St. Dunstan's coffeehouse. Such discussions also allowed scientists to try out half-formed theories and ideas. Hooke, however, had a reputation for being boastful, argumentative, and overstating his case. After an argument with Hooke in Garraway's, Flamsteed complained that he had "long observed it is in his nature to make contradictions at randome, and with little judgmt, & to defend ym with unproved assertions." Hooke, claimed Flamsteed, "bore mee downe with wordes enough & psuaded the company that I was ignorant in these thinges which that hee onely understood not I."

But Hooke's coffeehouse boastfulness was the unwitting trigger for the publication of the greatest book of the Scientific Revolution. On a January evening in 1684, a coffeehouse discussion between Hooke, Halley, and Wren turned to the theory of gravity, the topic of much speculation at the time. Between sips of coffee, Halley wondered aloud whether the elliptical shapes of planetary orbits were consistent with a gravitational force that diminished with the inverse square of distance. Hooke declared that this was the case, and that the inverse-square law alone could account for the movement of the planets, something for which he claimed to have devised a mathematical proof. But Wren, who had tried and failed to produce such a proof himself, was unconvinced. Halley later recalled that Wren offered to "give Mr Hook or me 2 months time to bring him a convincing demonstration thereof, and besides the honour, he of us that did it, should have from him a present of a book of 40 shillings." Neither Halley nor Hooke took up Wren's challenge, however, and this prize went unclaimed.