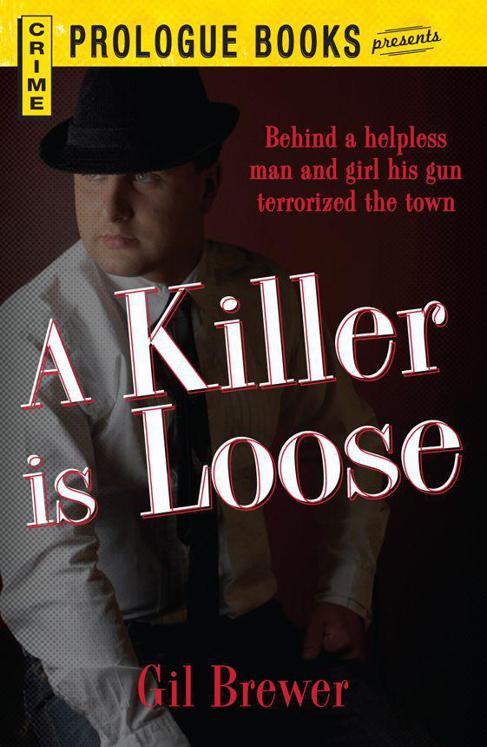

A Killer is Loose

Authors: Gil Brewer

Don’t Go Away Mad

Jake held the gun and looked at the guy beside me at the bar and said, “You want another?”

The guy reached out and poured himself one, all the time watching Jake and never spilling a drop. The guy’s face was dead white, as if it were molded from white marble.

“It’s a nice gun,” Jake said to me. “How much?”

“Thirty bucks.”

“I’ll give you twenty-five,” Jake said.

“All right.”

“Let’s see it,” the guy said.

Jake looked at him. Then he handed him the gun and got two tens and a five for me out of the cash register.

“It’s a nice gun, pal,” the guy said, turning to me.

“Give me the gun,” Jake said.

The guy just sat there looking at him steadily.

The drunk down the bar lifted his head. “I’m alcoholic. Will somebody buy me a beer?”

“Give me the gun,” Jake said.

“One beer,” the drunk said.

The guy sat there and looked at Jake. Then he tilted the barrel of the Luger on the edge of the bar and shot Jake Halloran in the head. The slug took Jake in the forehead, between the eyes, and went right on through and smashed the bar mirror.

The guy stepped away from the bar stool and walked toward me.

“Pal,” he said earnestly, “my name’s Ralph Angers. What’s yours?”

IS LOOSE

Gil Brewer

a division of F+W Media, Inc.

I

F

I

CAN TELL

all of this straight and true, and get Ralph Angers down here the way he really was, then I’ll be happy. It’s not going to be easy. There was nothing simple about Angers, except maybe the Godlike way he had of doing things. He was some guy, all right. In the news lately, you’ve read of men doing some of these things, like Angers. They were all red-hot under the same cold star when the wires snapped and Death became a pygmy. So I figure I’d better get this told. There are plenty of Ralph Angerses now on the streets, on the trains, in the bars, in the hotels, in the houses, at the ball game, and there’s no way on earth you can tell

who

, until it happens. Hell, no. So this is my story and how it happened with me, and how it ended. It ended simply, come to think of it. I guess it had to. It would take some devil of a mind to conceive horror enough for … But listen.

You know how luck works a cycle, good or bad, with both kinds equalizing when you score it out; so after enough bad you don’t worry at all because it’s got to change. Well, I’d gone six months beyond that, even. For three weeks I hadn’t bothered lying to Ruby about leaving the house mornings to look for work that wasn’t to be had. The game was played out. So I stayed home. I sat on the couch in the living room and watched her grow bigger and slower with our first kid, knowing he would be born any day now. Only this morning I couldn’t take it any longer. I knew what I had to do. I left the living room, went down the hall into our bedroom.

She was there on the bed, resting between mopping the porch and cooking lunch with nothing to cook. What a Ruby!

“Steve,” she said, “I had a pain when I was working. Maybe it’s a false alarm. But it won’t be long now.”

I didn’t look at her. I went over to the bureau and stood there with my hand on the second drawer. I knew she was watching me and I stared at the things scattered on the top of the bureau. A hairbrush and two combs and a nail file in a fake leather case with chromium trim and a dime-store hand mirror and a crumpled dollar bill and a ten-cent piece and a six pennies, one of them looking as if it had been socked two or three times with a drill press.

“It’s probably a false alarm,” she said behind me, and I heard the bed creak as she turned. “There hasn’t been any pain since I’ve been lying here.”

“Sure,” I said. Only it probably wasn’t any false alarm because the only false alarm in her life was when she married me. Quit thinking like that, I told myself. “Sure,” I said. “You just take it easy.” I pulled a little on the drawer. It was stuck.

“What are you doing?”

“Nothing.”

“I hate to think of an ambulance, or anything like that,” she said. “Be sure, Steve—just a cab, now.”

“Absolutely.”

“I wish I could have it home, like they used to.”

“Don’t talk like that. You know it’s better in a hospital. They got everything to work with. They know just what to do. Besides, it’s not sanitary at home.”

“Things certainly do change, don’t they? I was born in Daddy’s car right in the middle of Times Square.”

“I’ll bet your ma had a fit,” I said. “Knowing her.”

“Steve, you shouldn’t.”

“Anyway, there’s no Times Square down here.”

“What are we going to do, Steve? The doctor’s so nice, what he says about the bill and everything. But what will we do?”

“Like I say, don’t worry.”

I got the drawer open and stood there looking down at it all wrapped in the flannel cloth. I reached in and touched it and she began speaking again, only this time she was a little scared. She was thinking about it too much.

“Suppose it’s born in a cab.” The bed creaked. “Listen, hon, be sure and get me there in time. I don’t know what I’d do!”

“Don’t worry.”

“What are you doing there?”

“Nothing, I told you.” I took it out of the drawer and unwrapped the cloth and put the cloth back in the drawer. A Luger is a heavy good gun that squats in your fist the way a gun should, and just holding it you know what it’s got and that it will do what you want it to right where you think it should. That’s all you have to do with a Luger, just think where you want the slug, and it backs up hard and spits all at the same time, hard, solid, where you want it.

“I’m sorry about your guns, Steve. It’s a dirty shame we had to sell them all.” She meant it, she wasn’t just talking.

“Yeah.”

“You going to sell that one, too?”

“Don’t know. Could maybe get thirty dollars for it. Twenty-five, anyway. Friend of mine.”

“After all that work that gunsmith did on it for you?”

I shrugged.

“It’s the last one from your collection.”

“It’s not an item. You can pick ‘em up.”

“You wanted to keep it. That’s not enough money to help any, is it?”

“No.” I still hadn’t looked at her and I knew I might as well let her think I was going to sell the gun. Maybe if what I had planned for that bastard Aldercook worked, I wouldn’t have to sell it. He was a fine bastard, all right. He owed me the money and now I had to take a gun. Maybe I would sell it anyway. The gun was a hunk of temptation lying in the drawer.

I closed the drawer and went over and sat beside her on the bed, holding the Luger, thinking how there was a full box of twenty-five nine-millimeter Parabellum Czechs in the candy dish on the buffet.

Damn that Harvey Aldercook.

“How much money have we got?” Ruby said.

“I don’t know. Four dollars and sixteen cents.”

“Steve?”

I looked at her, looking away from the fine soft hard feel of cold blue steel, machined like glass and more than neighborly.

“Don’t sell the gun.”

“We’ll see. Listen, Ruby, I’m going downtown.”

“You weren’t thinking about selling it, anyway, Steve.”

We watched each other for a time. She was propped up on her elbows with the pillows bunched behind her shoulders and head. Ruby was a beauty and a winner, all the way. She was long and full in the body, eager, and big-boned with the bones fine and delicately shaped, and there was grace in every movement she made, even with the kid, like this. She had a broad quiet mouth and hair like a thick mass of waving saffron and clear eager blue eyes with all that fine quality she had shining out at you, glowing quietly out at you.

I stood and patted the calf of her leg. “I better get on with it.”

“Wait,” she said. “Get on with what?” She patted the bed but I didn’t sit down. She was wearing a bright blue dress with white collar and cuffs and white buttons all down the front shaped like hearts. She’d made the dress herself and she was a sweetheart. She looked fine.

“Something I want to attend to,” I told her. I kept rubbing the gun with my thumb and it was hard, cold, but beginning to warm up. It had black ebony grips. It would sock them in there like a .32 revolver on a .38 frame, only the Luger was nastier.

She turned her head away. “I knew this would happen.”

“It isn’t what you think.”

“Yes, it is. All those guns. I knew, I knew.”

“What the hell you want me to do?”

“Not that.”

I began to get that cramped feeling, like when somebody starts to crowd me. This was something I didn’t want to talk about. Not to Ruby, not to anybody. Maybe the money was her business, but Aldercook and how I got what belonged to us was my business and I didn’t want to talk about it. Just thinking about that pale slug of an Aldercook made my nose ache across the bridge.

“You think I’m going to stick up a bank?” I said.

“No. You’re too smart to pick on a bank.”

“Oh, Ruby, for God’s sake!”

“Not now, Steve. Not now. If it wasn’t for the baby, maybe I could understand. But now everything’s different.”

“You talk like I’m a crook. The only thing I ever stole in my life was two flashlight batteries out of a dime store when I was eleven, and a jug of cognac from a French

bistro

in Alençon during the war. And I got such a fool conscience I even sent the owner of that place five bucks when I got back in the States.”

“Yes. But it’s different now. I’ve been watching you, Steve.” She looked at me and I could see in her eyes all the not-quite-fear, the praying-pleading that she was wrong.

“Then what?” I said. My voice was a little rusty, the way it gets, and I was keyed up. “You can bat your head against the wall just so long,” I said. I said, “The South doesn’t want us, Ruby. And we can’t get back North, we can’t even eat right, and every damned body you see is driving a Cadillac and eating steak and we haven’t even got the Ford any more.”

“Since when do you like Cadillacs?”

“All right.” I walked over to the bureau and slammed my palm down on the top and the pennies and the dime jumped. Damned plywood.

“We own the house, don’t we?”

“Some house.”

“Can’t you take out a mortgage?”

I turned and shot a little laughter at her. I wasn’t thinking about how this was affecting her. I didn’t think about that until later. “It’s mortgaged to the throat and you know it. Another couple months we won’t have the house.”

“They like you here, Steve.” She patted the bed beside her again, only I didn’t take the hint. “Your father was born in this town and they remember him and they like you. Give it a chance. You have lots of friends in this town. Why, when we walk down the street everybody says, ‘Hi, Steve, how’s it going?’ And—”

“Yeah,” I snapped. “And they know just exactly how it is going, too. I tell you, they’re still fighting that war down here. Why can’t I get a job, then? This isn’t the depression, Ruby—this is a high time on the calendar. I was on the force in Jacksonville and maybe it wasn’t tops, but it was all right. Until that son-of-a-bitch jabbed his thumb in my eye and fixed it so I can’t see right. He ruined everything. I can’t fly a plane any more. They won’t renew my license. I’m an experienced mechanic until they see me trying to work with a screw driver or a wrench, or spot the way my hands get torn up jabbing them into the fan, or see the scars where I knock my head into every damned nut and bolt and sharp edge on an engine. ‘Can’t you see right, Logan?’ they say. ‘Is the light bad in yere?’ ‘I see fine,’ I says. ‘Just had a rough night, is all.’ ‘Well, we don’t tolerate rough nights, Logan, not at this garage. Sho, now, I reckon you stay on this yere job another week, you-all will maim yourself with a spark plug or mebbe get constipated on a gearshift knob.’ I hit him for saying that. He sat down in the grease pan. It’s just I get excited, Ruby. I can see all right. Distance is a little cockeyed, I’ll admit. But I can shoot a gun. Now tell me, how come I can shoot like that, but sometimes I have to feel my way up the porch steps? One-eye Logan. And that

one

keeps letting me down. I could cut that bird’s throat, him with his dirty thumb!”